Visual Arts Review: “Munch and Kirchner: Anxiety and Expression” — More Than Melancholic

By Peter Walsh

Yes, Munch and Kirchner were into angst; but they were also artists of great energy, talent, and daring, who found new ways of working and did much to shape the direction and force of modern art.

Munch and Kirchner: Anxiety and Expression at the Yale University Art Gallery, 1111 Chapel Street between York and High Streets, New Haven, CT, through June 24.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1896, Lithographic crayon printed in black and red, tusche, and scraper. Photo: courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery

The Norwegian artist Edvard Munch and the German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner met only once, in Cologne, in 1912. The scene was a major exhibition of modern art sponsored by the Sonderbund, or the “Special League of West-German Art Lovers and Artists,” whose membership included artists, curators, enthusiasts, and various art world professionals. Munch, the older artist, had already achieved a broad international reputation. He was presented in the show as part of an established generation of European modernists, represented there by more than 60 works, hung together in their own gallery. Kirchner, who had earlier been a founder of Die Brücke (The Bridge), the group of German modernists who established German Expressionism, had only two works on view.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, The Suicide, 1921. Woodcut printed in red and black. Photo: courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery

Kirchner’s ambition was rabid, and he must have felt slighted by the vast difference between Munch’s exhibition presence and his own. Nevertheless, the two artists met by chance and strolled amicably through the exhibition. Although they had dealers, patrons, and friends in common, they never met again. Kirchner’s pointed rivalry, however, continued. “He is the end,” he said of Munch. “I am the beginning.”

The Yale University Art Gallery’s exhibition Munch and Kirchner: Anxiety and Expression, with more than 60 works (mostly) on paper –especially prints — focuses on the many parallels between the two Expressionist artists, exploring “themes of anxiety, modernity, psychology and psychiatry, depression, and trauma.” The pairing is not a new one. As the exhibition catalogue reveals, treating Munch and Kirchner as a cultural, biographical, and psychological pair goes back at least as far as the German print collector and scholar Gustav Schiefler, who collected and wrote about both artists while they were in active careers.

Art historians link the two as leaders in the revival of hands-on printmaking — that is, printmaking as a core part of an artist’s creative practice. Hands-on print artists, which include major figures like Rembrandt, Dürer, and Degas, are directly and actively involved in the creation of their prints, making their printing plates and often even running them through the press themselves — experimenting with media, color, and effect in many variations, as did both Munch and Kirchner. At other times and with other artists, printmaking has been primarily a commercial publishing activity, in which the artist has a much more distant role, delegating all the printing and often even the creation of plates to specialist technicians, who may work from designs, drawings, or even large wall murals, which they adapt after the original paintings.

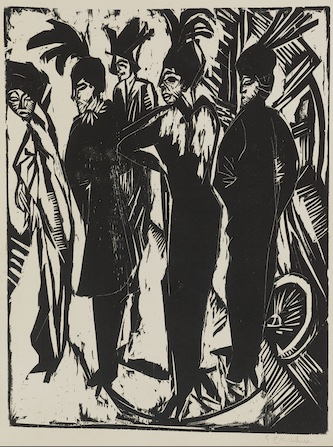

In his innovative lithographs and especially in the woodcuts he made, Munch came first, but Kirchner was right about one thing: Munch’s work is stylistically rooted in the 19th century, whereas Kirchner very much belongs to the 20th. Early in his career, Munch was labeled “the first Norwegian Symbolist.” A stroll past the Munch prints in the show many hallmarks of the neoromantic Symbolist movement and its decorative arts cousin, art nouveau: swirling lines, curling vegetation, women with long, flowing, loose hair (when mature female hair was traditionally bound up in public), dark woods, moonlit scenes by the seashore, moody, introspective colors, wide, anxious eyes. Kirchner lives in another universe and another century. His stylistic references are cubism, jazz, medieval art with its elongated forms, and the crude, expressionist prints of early Renaissance Germany. Figures are lean and vertical, hair short, clothing straight in profile and tight-fitting. Kirchner’s space tightens up, even in landscapes; it is the congested, barely controlled urban space of modernism. The dark moods go up a notch: this is a time when anything might happen and likely will.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Five Coquettes on the Street, 1914. Woodcut. Photo: courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery

In emphasizing the parallels, the show’s organizers have focused on themes of melancholia: early trauma (a childhood marked by death and mental illness for Munch; service in World War I and a subsequent breakdown for Kirchner); “Illness” (mental and physical; both artists were hospitalized at times for mental breakdowns and spent time in sanitariums). “Women/Love/Death and Anxiety” are the topics for another section. The “City” theme features scenes of “Bohemian” life, an unorthodox, sexually liberated approach to modern living that attracted both artists (Kirchner was known for studio gatherings featuring nudity and casual sex). Both artists’ self-portraits feature cigars and cigarettes; bottles and glasses clutter the café tables and tobacco smoke swirls through the air in Munch’s Kristiania (an older name for Oslo); prostitutes mingle with shoppers in Kirchner’s fashionable Berlin. The din in Kirchner’s cabarets is almost audible.

This is an exhibition organized by parallel themes and biographies. The lives of both artists ended up colliding with the culture wars of the 1930s and ’40s. The Nazi authorities declared Kirchner’s art “degenerate.” In 1937, 639 of his works were seized from museums and collections throughout the Reich; 25 were shown in the notorious “Degenerate Art Exhibition” that same year. In 1938, Kirchner committed suicide in Switzerland, where he had lived for many years and where he had first moved for treatment for mental and physical illness.

Munch died at 80 in 1944, in the last months of the Nazi occupation of Norway. He, too, had been declared degenerate. Some 82 works were purged from German museums. Munch lived in fear that the Nazis would seize the large collection of his work hidden on the second floor of his home. Fortunately, they did not, and other works removed from Norway by the Nazis, including the famous Scream, were bought by collectors and returned; 11 were never recovered.

Somewhat lost in all this is something the viewer should not miss. Looked at from a different angle, the Yale show could narrate a different story: the adventures of two artists of great energy, talent, and daring, who found new ways of working and did much to shape the direction and force of modern art.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Tagged: Edvard Munch, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Munch and Kirchner: Anxiety and Expression