Book Review: “Limitarianism” — An Idea Whose Time Has Come

By Ed Meek

In this pointed book about the harm done by the super-rich, Ingrid Robeyns is out to convince us that limiting wealth, and reallocating it, will result in a better life for all of us.

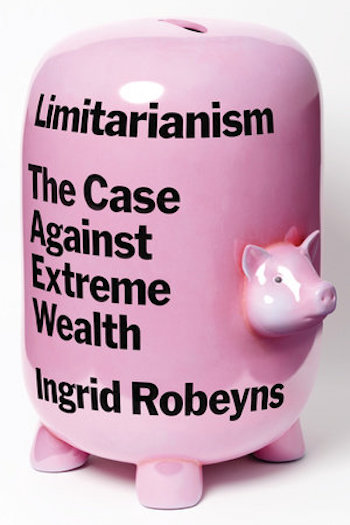

Limitarianism by Ingrid Robeyns. Astra House, 336 pages, $28.

Excessive wealth seems to be getting a little out of hand, wouldn’t you say? To take one jaw-dropping example, Jeff Bezos has a net worth of about $199 billion (according to CNN). Our government currently designates the poverty line in the United States: the cut off for annual income is $15,060. That’s where the safety net kicks in. Should the government also limit how rich someone can be?

Excessive wealth seems to be getting a little out of hand, wouldn’t you say? To take one jaw-dropping example, Jeff Bezos has a net worth of about $199 billion (according to CNN). Our government currently designates the poverty line in the United States: the cut off for annual income is $15,060. That’s where the safety net kicks in. Should the government also limit how rich someone can be?

In 2011 the Occupy Movement gained widespread support when thousands of people in New York City and around the world protested the concentration of wealth in the top 1%. Today, according to Statista.com, the top 1% holds almost a third of the wealth in the US. The top 10% controls two thirds of the wealth, which leaves the rest to be divvied up among the rest of us. Despite the widespread popularity of ideas promulgated by the Occupy protests, critics pointed out that the group made no concrete policy demands. In her timely book Limitarianism, Utrecht University academic (Economics and Ethics) Ingrid Robeyns provides a solution to the concentration of wealth that so alarmed that movement.

Because of the growing disparity between the rich and the rest of us, capitalism is not working very well for most Americans. Anne Applebaum in Twilight of Democracy points out that the widening wealth gap is leading people to embrace authoritarianism, enticed by the promises of a strongman who will avenge the have-nots against the elites (or will return the country to the good old days). Sound familiar? While President Biden and The New York Times continually assure us that the economy is just great, with plenty of jobs and inflation pretty much under control, most Americans think the economy is poor and the country is headed in the wrong direction. Robeyns suggests why there might be this kind of disconnect between the powerful and the powerless.

Robeyns is out to convince us that limiting wealth, and reallocating it, will result in a better life for all of us. Does anyone need to have a billion dollars?, she asks. According to economist Jeffrey Sachs, (whom she cites) “2775 people in the world are billionaires.” How about Elon Musk with his $193 billion (according to Forbes). Musk bought Twitter with $40 billion and is now reshaping this powerful media tool to fit his twisted agenda. Musk also owns half the satellites in orbit. Isn’t that a little too much money and power for one individual? Robeyns suggests setting a personal wealth limit of 10 million dollars. The principal reason she gives for redistributing wealth: it is the moral thing to do. It is a matter of fairness. You can hear echoes of this in such current progressive phrases as “climate justice” as well as calls for “equity.”

Robeyns argues that redistributing wealth will solve the problem of poverty. As Matthew Desmond tells us in Poverty, by America, the US has had the same rate of poverty (12%) for over 50 years. That’s 40 million poor people, far and away the most of any First World country. In comparison, a little over 1% of the population of China lives in poverty. Meanwhile, the federal minimum wage remains, since 2009, at $7.25 an hour. That just about lifts a person to poverty level. To make matters worse, Desmond and Robeyns tell us that it is the top income earners who are reaping the lion’s share of benefits from government tax breaks via mortgage payments, lower taxes on capital investments than on labor, tax breaks for losses, and low taxes on inheritance.

Robeyns illustrates how the rich work the system and use their wealth in ways that hurt everyone else. They buy political favors, influence the mainstream media, and promote a culture of acquisition by propagandizing the merits of neoliberalism: a belief in individualism, private ownership, and free trade. Neoliberalism gained traction under President Reagan and was embraced by Clinton, then the Bushes and Obama. Now the tide is beginning to turn under Biden and the “social democrats,” who are attempting to put together a refreshed version of the New Deal.

Robeyns also claims the wealthy are standing in the way of making progress on the climate crisis: the super-rich are leaving the biggest carbon footprint with their mega-mansions, car collections, yachts, and private jets.

Philanthropy is not the answer according to Robeyns. With a few exceptions, philanthropists divert money from where it might have been better spent elsewhere. Bill and Melinda Gates are an exception with their work on world health and green technology. Too many rich donors use their sizable tax-deductible contributions to enrich elite colleges and influence politicians to perpetuate the privileges of the upper class. Robeyns even claims that ‘limitarianism’ will be good for the rich. Avoiding taxes, finding friends and lovers they can trust, maintaining multiple estates must be a considerable psychological burden, she argues.

How should we tackle the problem of excessive wealth? Robeyns wants much more progressive income taxes. After WWII, tax brackets went as high as 90% on income. The top bracket today is 37%. She suggests a CEO to average worker income ratio of 12 to 1 (it’s 344 to 1 now according to the Economic Policy Institute). She’d like higher taxes on capital and the elimination of tax havens. And last but not least, she’d like much higher taxes on inheritance. Inheritance is not earned or deserved, she insists. She wants to limit it to $400,000.

Robeyns is not alone in her call to address the pernicious effects of the concentration of wealth. Biden is interested in raising taxes on the rich and eliminating tax havens. Politicians on both sides of the aisle have brought up closing the wealth gap (from Bernie Sanders and AOC to Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio). An organization made up of high-rollers, Patriotic Millionaires, is working to address the wealth gap. But, because both political parties in the US have been dedicated to neoliberalism for so long, a significant number of Americans have turned against the government, which is seen as foe rather than friend. The challenge is daunting, but rebalancing and regulating capitalism will be a necessity if we are going to deal with the many internal and external threats we are now facing. Thus Limitarianism is well-worth considering and debating.

There is an ongoing argument about what is America’s biggest problem. Some would claim it is the conflicts between nations. The rise of China, the aggression of Russia, the increasing discord in the Middle East. Others would argue that it is the challenge of climate change. Or maybe it is the issue of growing disinformation in the media, the fictions sold as truths by Fox News, Truth Social, Facebook, X and Tik Tok, expanding into the spread of conspiracy theories, gaslighting, and the blurring of reality. Is there a thread that runs through all these difficulties? For Robeyns, the unprecedented concentration of wealth and power over the past 40 years fits the bill. And the only way to ameliorate that damaging wealth gap is to redistribute wealth and power.

Ed Meek is the author of High Tide (poems) and Luck (short stories).

Mr. Meek is a poet. If someone with a vague and passing interest in poetry opined in these pages that the meter of a given poem was “getting a little out of hand, wouldn’t you say?”, readers would wonder what qualified the author to remark as much. And so it is with Meek’s take on economics.

There are longstanding criticisms of confiscatory tax rates, proscribed CEO-to-lowest-rung-worker income ratios, income caps, and much else recommended in Robeyns’s book, by knowledgeable economists. It is not at all sure that inequality underlies all other human woes, or even what “neoliberalism” means. Meek is welcome to disagree with those claims, but his neglect to recognize that such criticisms exist is disqualifying. It would be unsurprising if Robeyns didn’t bring them up either, but a responsible critic who understood the topic from more than one perspective would have noted as much.