Book Review: A Fascinating Meditation on Jewish Maps of Time

Palaces of Time is a exquisitely illustrated, elegantly written account of the history of Jewish calendars in early modern Europe, as well as a meditation on what they represented.

Palaces of Time: Jewish Calendar and Culture in Early Modern Europe by Elisheva Carlbach. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 304 pages, $35.

By Susan Miron.

When Professor Elisheva Carlbach (Jewish History, Culture, and Society at Columbia University) first examined the collection of Jewish handwritten calendars at the New York Public Library in 2002, it was—for her—love at first sight. This “garden of scholarly delights,” a pile of colorful calendars small enough to fit in the palm of her hand, seemed “a reminder and symbol of human time, its stations marked in tiny ciphers by a diligent hand.” History at its most personal and astonishing was simply too captivating to ignore.

The result is a exquisitely illustrated, elegantly written account of the history of Jewish calendars in early modern Europe, as well as a meditation on what these calendars represented—profound reflections of the Jewish experience as it passed through time.

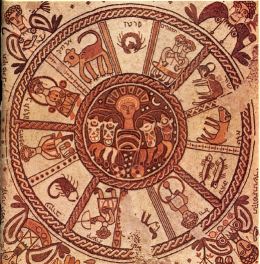

Professor Carlebach (whose field of expertise is the Jews of early modern Europe) sets the stage for her examination of early Jewish calendars (siffrei evronot) by showing how calendars in the early modern period in Europe functioned both as an a system for accounting for time as well as an artifact for displaying it. Starting in the sixteenth century, she writes, “the calendar emerged as a locus of religious, cultural, and political conflict.”

The expansion of print was not only about providing information; it also served as a tool for those interested in shaping new political and dynastic loyalties as well as cultural change. Before this, during the medieval period, calendar-calculating (computus) literature told of “reckoning of time and holy days by means of the hand and fingers” or even using finger joints to keep track of the lunar and solar cycles.

Calendars, prepared by hand, were often the products of the person who had calculated them. Most calendars, rather than covering one specific year, had tables for computing any year’s calendars. These perpetual calendars, based on cycles of years, continued even after printing was invented.

Eventually, in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, material like those in peasant almanacs (“shepherds’ calendars” in English, Volkskalender in German) was added to make these calendars more marketable—dietary, medical, and seasonal hygienic information, good times for bathing, sexual relations, bloodletting, pruning trees, buying clothes, or even the best months for moving one’s household.

Professor Carlebach points out that these faux-naïve calendars were hardly meant for shepherds and peasants, but for those who read to and instructed them. Their popularity, regardless of who consumed them, was reflected in the 150,000–200,000 copies that were printed annually in seventeenth and eighteenth century France alone.

As the printing industry matured, calendars evolved from falling somewhere between sacred literature and ephemera into their own wildly diverse print category, with specialized volumes for a multitude of special interest groups, some comprehensible even to illiterates. There were astronomical, geographical, military, historical, economic, and gardeners’ calendars.

“Calendars,” Professor Carlebach argues, “were used to disseminate not only information, but also values, able to be manipulated, edited, censored, and controlled.” Thus, they “emerged as one of the important didactic and polemical instruments of the age . . . The calendar had become a platform on which early modern societies played out the great political religious, and national dramas of their time.”

Jewish calendars impart fascinating historical insight into how believers led an often-perilous existences in Christian Europe, particularly in German lands. Jewish early modern calendars were different: they were in Hebrew and started their year on the first day of their month of Tishre, Rosh ha-shanah. Most were created to be used for only a year, but “these humble maps of time” were enormously important to their owners, keeping them abreast of time in both the Jewish world and the world in which they lived. Jews could not remain ignorant of important dates of the religious culture’s majority; their lives literally depended on knowing market dates and the dates of Christian religious observances.

The Jewish calendars “embodied the need to understand, internalize, and instruct in the culture of the other,” while working out strategies of resistance to the other’s culture. “Virtually every European Jewish calendar carried a full Christian calendar in its core section . . . While Jewish calendars might seem to reflect and mandate Jewish separation and distinctiveness, a closer inspection reveals a complex story of cultures so deeply intertwined that they could never be completely unraveled,” Professor Carlebach concludes.

For example, to keep its Easter calendar totally free of Jewish influence, the Church bizarrely insured that the holiday would never coincide with Passover: it committed itself to moving Easter from one date to another every year. “Thus it has only managed to immortalize its awareness of—as well as actual dependence on—the latter, . . . a most ironical reminder of some fundamental Jewish influence.” The Christian calendar came after the Jewish calendar, and Jewish scribes and printers did their best to resist its power by inserting small barbs, resisting just a bit the culture that enveloped them.

“Church Time and Market Time,” discusses not only the history of the major markets like Frankfurt, but the exact timing of the occurrence of the Tequfah, the turn of the four seasons (solstices and equinoxes, the turning point of the sun). Observance of the four tequfah shows up throughout siffrei evronot, which invariably insisted that Jews refrain from drinking water left standing uncovered during these times of seasonal turning points.

“The exposed water, it was taught, could have been struck or contaminated by harmful substances during this critical time, or in later texts, turned to blood,” Professor Carlebach explains. Jewish legal experts at the time went along with the notion of thrusting a metal implement into the “contaminated” water, thus turning “calendrical precision into a matter of life and death.” A late-fifteenth-century, Dominican monk, Erhard von Pappenheim, one of many to ridicule this custom, went on to become the first to charge that the first matzot eaten for Passover were made with Christian blood.

Market dates were also fraught with danger. Jewish traders needed to know their Christian neighbors’ religious customs and festivals if only for self-protection. The important markets and fairs showed up on on almost all the Jewish calendars throughout Eastern and Central Europe, in England, and in France. These fairs, “regularly scheduled events in the cycles and cultures of Jewish life,” were crucial parts of the economic life of early modern European Jews, many of whom spent months at a time on the road, returning home only for major holidays and family events.

“If Jewish life in premodern times,” Professor Carlebach writes, “sometimes felt like a stifling enclosure, markets and fairs served as windows, allowing fresh ideas and impressions in, and allowing non-Jews to look in at the Jewish culture through a lens less distorting.”

It has often been noted that, since the Destruction of the Second Temple, Jews made up for their lack of a sacred space by creating sacred time, especially the Sabbath. The calendars we see in Palaces of Time show how the Jews have always negotiated a precarious balance among cultures, languages, and times.

Tagged: Calandars, Early Modern Europe, Elisheva Carlbach, Harvard University Press, Hebrew, Jewish