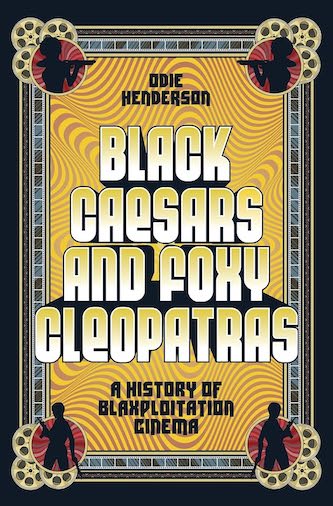

Book Review: “Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras” — Celebrating Blaxploitation Cinema

By Steve Erickson

Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras celebrates Blaxploitation as a positive as well as a necessary turning point in American cinema.

Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxploitation Cinema by Odie Henderson. Abrams Press, 292 pages, $27.

What was Blaxploitation? It has always been a contentious word: Los Angeles NAACP head Junius Griffin initially intended it to be an insult. Ironically, two of the movies that did the most to define the genre — Melvin van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback Baadassss Song and Gordon Parks’ Shaft — were released before the term had been coined. Melvin van Peebles strenuously insisted that that his film wasn’t Blaxploitation. Boston Globe film critic Odie Henderson’s history of the genre looks at these and other ambiguities, but from the perspective of the long view, running down what was produced from 1970 to 1975 and offering chapters on key movies.

What was Blaxploitation? It has always been a contentious word: Los Angeles NAACP head Junius Griffin initially intended it to be an insult. Ironically, two of the movies that did the most to define the genre — Melvin van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback Baadassss Song and Gordon Parks’ Shaft — were released before the term had been coined. Melvin van Peebles strenuously insisted that that his film wasn’t Blaxploitation. Boston Globe film critic Odie Henderson’s history of the genre looks at these and other ambiguities, but from the perspective of the long view, running down what was produced from 1970 to 1975 and offering chapters on key movies.

The fact is, Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras showcases the full range of films about Black people during this time period. Blaxploitation is used as an organizational conceit. For example, John Berry’s Claudine receives a glowingly enthusiastic chapter, yet Henderson insists that it’s not a Blaxploitation movie. He praises it as “one of the best examples of counterprogramming the era had to offer, and one of the kind of working-class comedy that was never offered to Black people.” (One of Henderson’s interview subjects, fellow critic Robert Daniels, is equally effusive about the film.) Henderson isn’t all that crazy about Sweet Sweetback Baadassss Song – rightly, he praises van Peebles’ underrated comedy Watermelon Man, in which a bigoted white man wakes up to find out he’s become Black. The critic points to Gordon Parks, Jr.’s Super Fly as the high-water mark of Blaxploitation.

Like most movements, Blaxploitation’s early innovations led to watered-down sequels and lazy knock-offs. The true inventors, such as Bill Gunn, were left behind. To this day, Warner Brothers refuses to release Gunn’s first film as a director, Stop!, while his art/horror hybrid Ganja and Hess was sliced and diced into an unintelligible mess for its initial release. Henderson approvingly quotes Los Angeles Times writer Cecil Smith’s charge that “Shaft on TV made Barnaby Jones look like Eldridge Cleaver.” The chapter on Live and Let Die demonstrates that even the James Bond franchise felt like it had to hop on the Blaxploitation bandwagon — even if the results were limp and insulting.

There are no new interviews from actors or filmmakers (except producer Jeff Schectman), but Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras has been extensively researched. Henderson put in many hours at the library, looking up articles and reviews on period’s Blaxploitation films. Unsurprisingly, most of these journalistic pieces are rather baffled. At that point (and even in the present day), white film critics dominated the profession; daily newspapers in the ‘70s rarely hired (or brought in) Black writers to review these movies. On top of that, the growing minority affection for the vitality of B-movies and cult cinema wasn’t represented by their hires.

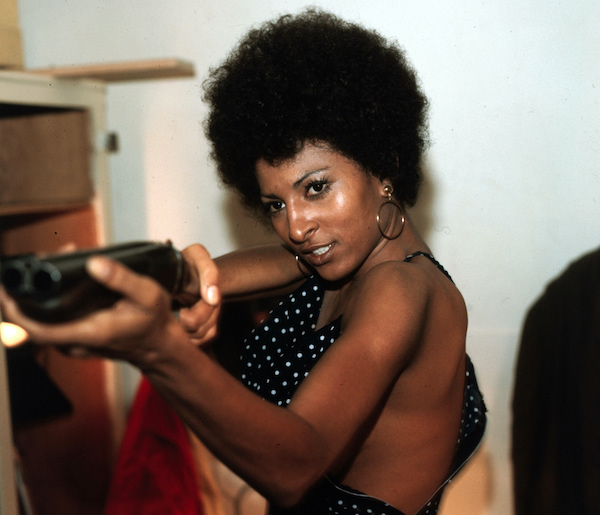

Pam Grier in 1973’s Coffy. Photo: AIP/Photofest

The daunting lack of Black representation in American cinema before the late ‘60s no doubt led to the notion that one had to choose between the cocaine dealer anti-hero of Super Fly and the “positive images” of Black people’s lives served up by films like Martin Ritt’s Sounder. (Praising both efforts, Henderson rejects this false dichotomy.) Along the way, Henderson offers plenty of examples of media hypocrisy regarding Blaxploitation. The Chicago Tribune refused to print the full title of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadassss Song in Gene Siskel’s review, because “ass” was too vulgar. But they had no problem with letting Siskel spell out the N-word. Mainstream magazines denounced Blaxploitation movies as a negative influence on African-Americans — and published ads for cigarettes and alcohol on the next page. The notion that marginalized people have a right to an id or are eager to enjoy fantasies which shouldn’t be acted out in real life was alien to society (even to Black activists). The burden of well-intentioned but, in practice, often patronizing expectations exerted by progressive politics on art by minorities was in full force (and still exists in different forms), even though no one expected admirable behavior from the white male heroes of action movies made at the same time. Today, it seems utterly bizarre that anyone would be offended by what goes on in Shaft; if anything, it’s less violent than the typical cop movie of 1971.

A scene from Ralph Bakshi’s live-action/animated satirical crime film Coonskin.

That said, Henderson never denies the stereotyping as well as the ugly extremes of violence and casual homophobia that’s exploited in a number of the movies he covers. Yet, in the end, Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras celebrates Blaxploitation as a positive as well as a necessary turning point in American cinema. And Henderson makes his provocative case with wit and honesty. Once the book gets past 1975, a year where the genre’s decline begins, its subject becomes more diffuse. Blaxploitation’s influence would eventually be seen and heard in hip-hop (where numerous rappers have sampled its soundtracks and expanded upon the themes of songs like Curtis Mayfield’s “Pusherman” and James Brown’s “Down and Out In New York City”), ‘90s “hood movies,” and affectionate parodies.

Henderson’s origin story for the book is told in his introduction, where the writer describes working at a video store alongside Tee, “the most militant Black man I’d ever met.” The entire store feared Tee’s reaction to Ralph Bakshi’s scabrous Coonskin but after he finally saw the live-action/animated satirical crime film, Tee criticized its racism but concluded “we win in the end, so I can forgive it.” Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras examines what that win means in the context of a rigged system, where progress in Black artists’ participation in American cinema has been partial and cyclical. Refreshingly, without setting his critical smarts aside, Henderson puts Black audiences’ pleasure at the center of this illuminating book.

Steve Erickson writes about film and music for Gay City News, Slant Magazine, the Nashville Scene, Trouser Press, and other outlets. He also produces electronic music under the tag callinamagician. His latest album, Bells and Whistles, was released in January 2024, and is available to stream here.