Book Review: “Yves Montand: The Passionate Voice” — An Activist Entertainer

By Steve Provizer

Singer/actor Yves Montand’s life and career are particularly fascinating because they illuminate a telling difference between the mid-20th century political-cultural milieus of France and America.

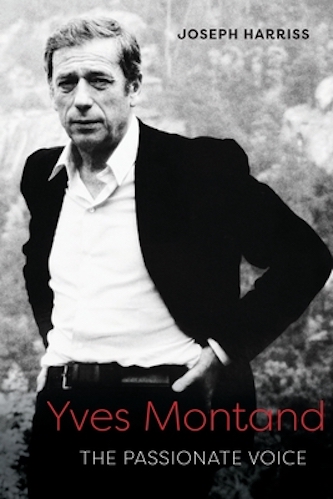

Yves Montand: The Passionate Voice by Joseph Harriss. University Press of Kentucky, 310 pages, $30.

Actor-singer Yves Montand went from a dirt-poor upbringing in rural Italy to international stardom — an interesting tale that’s well-told in this biography. The story is that much more fascinating because it illuminates a telling difference between the mid-20th century political-cultural milieus of France and America. In France, an esteemed entertainer like Montand was able to also be a leftist political activist. In America, that was simply not possible.

Montand’s politics were shaped by his father Giovanni’s devotion to the cause of Communism in Italy. This allegiance to the C.P. set Giovanni up as a target for the growing Black Shirt (Fascist) movement. Eventually, he was forced to flee to Marseilles, France. The family followed him there and Yves (nee Ivo Simoni) spent the rest of his adolescence in that bustling, diverse port city.

Montand started working at manual labor jobs at age 11 and went onstage at 17. Wracked with performance anxiety, which remained with him the rest of his life, he achieved some early success. He performed a cabaret act — what we might call vaudeville in America — singing, dancing ,and doing imitations of Maurice Chevalier and Donald Duck (!). A well-known impresario Emile Audiffred noticed him, and got Montand better bookings. The German invasion of France put a halt to his career and he worked as a boilermaker and longshoreman. Pétain worked out a deal with the Germans that left the South of France more open than Paris and vicinity, so Montand was able to go back on stage. Still, after the Allies invaded North Africa, the Nazis turned the thumbscrews on Marseille, beginning the systematic elimination of “undesirables.” Montand’s career again stalled.

Montand seems to have maintained as much of a distance as possible from what was happening around him. He was supposed to enter Pétain’s Youth Corps, almost a quasi-branch of the German Army, and work to entertain the troops. He avoided service, becoming a draft dodger, yet was not interested in volunteering to fight in the French Underground.

Impresario Audiffred managed to have him booked into a large theater, the ABC Music Hall in Paris, where he went over well. Audiffred then chose him to be a last-minute replacement in a show at the Moulin Rouge that was headlined by Edith Piaf. The two became lovers for the next 2 years. From this point on, Montand’s success as a performer was never in doubt.

His stage preparation was meticulous — each physical and musical movement very carefully planned and thoroughly rehearsed. Montand dressed plainly, in an open shirt and trousers; his presentation was straightforward and calculated to put him across as sincere. Physical labor had given him the body of a worker; the media labeled him “The Singing Prole” and the “Working Man’s Troubadour.” He seemed down to earth and without airs. Oddly, I had the chance to witness this for myself.

When I was in Paris in 1976 I got work doing background at the Studios de Boulogne for a film called Le Sauvage, released in the U.S. as Lovers Like Us. The film starred Catherine Deneuve and Montand. Deneuve was not much in evidence on the set. Montand, on the other hand, was. It was very hot, and I vividly remember him sitting on a chair with the chaos going on around him. He held one of those little fans to try and cool down and would pass a word with whomever stopped to talk. He seemed available and without airs.

Catherine Deneuve and Yves Montand in a scene from Lovers Like Us.

In fact, for the previous 25 years, he had been breathing very ratified air, part of a circle of elite intellectual and artistic friends. This was especially the case after he began an affair with the actress Simone Signoret, whom he ultimately married. (She reflects on their relationship in her autobiography, Nostalgia Isn’t What it Used to Be.)

Rather than concentrating on Montand’s upward singing and film career trajectory, I would like to focus on how his political activity interfaced with what was happening in the U.S. As referred to earlier, his father (and his brother) were deeply invested in the Soviet experiment. He followed this ideological path as well. He and Signoret were very involved in the left-wing politics of the era. He often sang at demonstrations, signed petitions, was highly critical of France’s role in Southeast Asia, often singing anti-war songs like Quand Un Soldat in his performances.

The couple was well aware of the Red Scare in the U.S. In fact, because of his politics, Montand was refused entry into America for a number of years. Montand and Signoret helped to give work, when they could, to expatriate Americans whose careers had been derailed by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). They heard of Arthur Miller’s anti-McCarthy drama The Crucible and obtained the rights. In 1954 the pair starred in a production of the play, the script designed to highlight the current American witch hunt. Miller was going to come to Paris to see the staging in 1955, but he was not allowed to leave the U.S. because he had refused to name names in front of HUAC. (Signoret and Montand were cast in a 1957 film version of the drama.)

In 1956, Norman Grantz of Jazz at The Philharmonic fame saw Montand perform and wanted to bring him over to perform his one-man show on Broadway. Grantz had enough political juice to get Montand a visa. The play they co-produced on Broadway was a solid hit, introducing the performer to American audiences, paving the way for more concerts and future work in Hollywood films.

In 1956, Norman Grantz of Jazz at The Philharmonic fame saw Montand perform and wanted to bring him over to perform his one-man show on Broadway. Grantz had enough political juice to get Montand a visa. The play they co-produced on Broadway was a solid hit, introducing the performer to American audiences, paving the way for more concerts and future work in Hollywood films.

That same year, 1956, Russia entered Budapest and crushed the Hungarian struggle for freedom. It was a grave disappointment to Montand, who had continued to cleave to a romantic vision of Soviet Communism. Given his personal and family history, he was torn because he had been scheduled to do a tour of Eastern Europe. Montand knew that if he went, he would be seen as supporting the Soviets. If he did not, he would be condemned by some as backing “the reactionaries.” He received threats from both sides. But, after a German producer decided to cancel a film Montand was to be in if he went to Eastern Europe, the performer declared that he would not submit to that kind of blackmail and did the tour.

Montand’s next important political interface was with the aspiring Greek director Costa-Gavras and writer Jorge Semprun. Semprun was a Spanish communist, screenwriter, and former resistance fighter. Because of his communist affiliations, Costa-Gavras had been denied entry to college in Greece and then a visa into the U.S. Montand and Signoret helped the filmmaker raise the funding for — and then starred in — his first film, Sleeping Car Murders. Montand would later star in Costa-Gavras’ overtly anti-fascist political films Z and State of Siege. In 1968, Russia entered Czechoslovakia and quashed a fledgling democratic movement. Montand and Signoret performed in Costa-Gravas’s 1970 film The Confession, an indictment of ruthless totalitarian methods. That movie was banned in Czechoslovakia for 20 years, until the Berlin Wall fell. In 1990, Montand was invited to Poland to present the Jan Palach Prize, named for “the twenty-year-old student who had been immolated in the city’s main square in 1969 to protest the invasion by Warsaw pact troops the previous August,” and was welcomed as a hero by President Vaclav Havel.

During the ’70s, Montand’s politics moderated. He adhered to a pacifist stance, doing benefits for the Chilean Refugee Relief Fund and adopting other human rights causes. He was popular enough that there was a movement in France to have him run for president. He mulled it over briefly, and then declined.

Yves Montand and Mylene Demongeot in 1957’s The Crucible (aka Les Sorcieres de Salem)

No high-profile American performer of the time had the freedom to take such contrarian, leftist political stances. Montand was able to be an activist for decades while still remaining a successful popular artist. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, American folk artists took strong leftist positions — Joan Baez, Pete Seeger and others. Ditto the Beats — although they were less specifically political. But these were all, in a sense, niche artists and performers during that period. Not until the late ’60s do we see the first glimmers of overt political statements coming from well-known American entertainers, a sign that the hunt for Red Commies in the culture had faded.

Still, look at the travails of the renowned who dared to be outspoken against the Vietnam War and theUS government: Muhammad Ali (banned from boxing, put in prison), the Smothers Brothers (cancelled), Martin Luther King (assassinated) and Jane Fonda. Interestingly, in the early ’60s, Fonda was in Paris shooting a film and she visited Montand and Signoret. She learned a great deal about the French misadventures in Southeast Asia from them. These conversations sparked a political awakening in Fonda. However, rather than receiving the kind of public acceptance proffered to Montand and Signoret, Fonda led ‘peacenik’ actions that led her to being dismissed and castigated as “Hanoi Jane.”

This history may have some lessons to teach us at a time in which conspiracy theories hold as much weight as facts. But what would they be? There is no single entity like HUAC passing summary judgment on the purity of an American citizen’s politics. Yet we are polarized in much the same way, a hardening of opinion that is no less frozen in place than the division that propelled the deviltry of McCarthy and his minions 75 years ago. It is the return of demonization — and questions about what the response of prominent American artists should be — that gives Yves Montand: The Passionate Voice unusual relevance.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Arthur Miller, Catherine Deneuve, Joseph Harriss, Simone Signoret, University Press of Kentucky, Yves Montand

From Nostalgia Isn’t What It Used to Be:

Montand on following their consciences: “From now on we’re going to be on bad terms with everybody — but on what good terms we’ll be with ourselves!”

Excellent review, Steve. Your decision to focus on the political underpinnings of Montand’s life and art is good one–and it helps shed light on some of his film choices. The Costa-Gavras’ films, especially Z and The Confession, were eye-opening to me when I was a young soldier. Influenced in some way by these (and the general surround of the late 60’s and early 70’s–including an encounter with Jane Fonda when she was doing her anti-war tour of US military bases), I became a conscientious objector and was eventually given an honorable discharge.

On the subject of U.S. actors and their willingness to use their public recognition for good, I think of Henry (and Jane) Fonda, Bogart, Heston, Belafonte, Brando, and some others who were upfront in the causes of civil rights, anti-racism, etc. In a modern era, certainly Warren Beatty, Barbra Streisand, Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Robert Vaughn, and others have borne witness. Among the newer generation of actors, DiCaprio comes to mind. Among the ranks of musical performers and professional athletes, there are many, But in today’s hyper-polarized climate, it’s easy to see why there’s reluctance, and for people who aren’t “too big to fail” the cost can be dear.

Thank you, Daniel. I was a C.O. myself and the main spiritual source that I used to convince my draft board was John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.”

Yes, there has been an improvement in the climate and a number of artists have stood up for what they believe. There’s still blowback, but no recriminations as dire as during the mid-20th century.

Great overview of a distinguished artistic and social life.Z knocked me out when I saw it. I’d put Sean Penn on the list of artists standing up. Jane Fonda inspired me to try and get her an honorary degree at Emory which was shot down by women on the committee because they thought she had had plastic surgery and would be a bad role model for the female students……..

Thanks Steve P!

Thank you, Vinnie. Z knocked me out too-saw it at the Exeter St. Theater. I watched it again recently and it’s amazing how strong Montand’s impact is despite the fact that he is only onscreen for 15 minutes.