Book Review: George Scialabba’s “Only a Voice” — Time to Roll Up Our Sleeves

By Daniel Lazare

It’s good to discover that George Scialabba is as lively as ever and that Only a Voice is filled with provocative arguments that make the reader want to argue right back.

Only a Voice: Essays by George Scialabba. (Verso, 336 pages)

George Scialabba is a moderate man stranded in immoderate times. Only a Voice, his sixth collection of essays, brings together articles he’s published over the years in the Boston Review, Raritan, Salmagundi, the old Village Voice, and other such places. The subjects are literary and political, and although a man of the left, Scialabba has a curious sympathy for cranky thinkers on the right such as T.S. Eliot, D.H. Lawrence, and the gloriously reactionary Ivan Illich. What he likes about them is their bravery in going against the grain. Their criticisms may be out of whack, but they can be biting, perceptive, and valuable. Lawrence, who Bertrand Russell once said had “developed the whole philosophy of fascism before the politicians had thought of it,” wrote a lot of silly stuff about sex and feminism. But once he finished describing gamekeeper Oliver Mellors plaiting all those flowers in Lady Chatterley’s hair, he was still left with the problem of what to do after modernity has swept away all those “ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions” and other such foolery with it. Now that they’re gone, what’s left? As Scialabba puts it: “If the beliefs that formerly made life seem worth living – beliefs about God, political authority, racial uniqueness, and sexual destiny – if these are seen to be illusions, then what does make life living?”

George Scialabba is a moderate man stranded in immoderate times. Only a Voice, his sixth collection of essays, brings together articles he’s published over the years in the Boston Review, Raritan, Salmagundi, the old Village Voice, and other such places. The subjects are literary and political, and although a man of the left, Scialabba has a curious sympathy for cranky thinkers on the right such as T.S. Eliot, D.H. Lawrence, and the gloriously reactionary Ivan Illich. What he likes about them is their bravery in going against the grain. Their criticisms may be out of whack, but they can be biting, perceptive, and valuable. Lawrence, who Bertrand Russell once said had “developed the whole philosophy of fascism before the politicians had thought of it,” wrote a lot of silly stuff about sex and feminism. But once he finished describing gamekeeper Oliver Mellors plaiting all those flowers in Lady Chatterley’s hair, he was still left with the problem of what to do after modernity has swept away all those “ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions” and other such foolery with it. Now that they’re gone, what’s left? As Scialabba puts it: “If the beliefs that formerly made life seem worth living – beliefs about God, political authority, racial uniqueness, and sexual destiny – if these are seen to be illusions, then what does make life living?”

It’s a good question, and Lawrence is to be commended for asking it just as Scialabba is to be commended for bringing it up. “Gloomy or arrogant,” Simone de Beauvoir said of the 20th-century conservative, “he is the man who says no; his real certainties are all negative. He says no to modernity, no to the future, no to the living action of the world; but he knows that the world will prevail over him.” This describes Eliot to a T, the subject of another Scialabba voyage to the dark side. Eliot is the self-described “classicist in literature, Anglo-Catholic in religion, royalist in politics,” who nonetheless wrote some of the most brilliant poetry in history. Only a Voice labors to find something positive to say about Eliot the man and does not come up entirely dry. It turns out that the author of “The Wasteland” and “J. Alfred Prufrock” also abhorred the “dictatorship of finance,” expressed a certain sympathy with communism, opposed censorship, and loathed advertising, as Scialabba does as well. So if you can put aside the anti-Semitism if only for a moment, Eliot turns out to be a not-entirely bad guy who had things to say that are relevant.

Illich, the subject of a 2017 essay titled, appropriately enough, “Against Everything,” seems especially to Scialabba’s liking. Born of Jewish and Catholic parents in Vienna in 1926, he and his family fled the Nazis and made their way to the United States where, after a few years as a peripatetic grad student, he became a priest in a poor Puerto Rican parish in New York. Illich was named vice-rector of the Catholic University of Puerto Rico in 1956 and then, after more wandering about, opened a language school and research center in Cuernavaca, Mexico, that Scialabba describes as “a seedbed of sixties radicalism.” This may suggest that he was a standard-issue forward-looking progressive. But in fact Illich was a latter-day Don Quixote who tilted at modernity and everything in it. He denounced public education because it “serves as a ritual of initiation into a growth-oriented consumer society.” He denounced medicine, the legal system, mass entertainment, and the automobile on the same anti-modernist grounds – because one “produces patients,” as Scialabba puts it, another “produces clients,” a third produces passive audiences, and a fourth provides an illusion of speed when in fact it leaves commuters mired in traffic. “As production costs decrease in rich nations, there is an increasing concentration of both capital and labor in the vast enterprise of equipping man for disciplined consumption,” Scialabba quotes Illich as saying. Like a goose on a foie-gras farm, modern man is force-fed commodities that he doesn’t need or want but which capitalism requires that he consume.

All of which may sound Marxist, but is really the opposite since Illich’s goal is to abolish modern production rather than revolutionize it so as to raise it to a higher level. “Illich’s advice to the Peace Corps volunteers who came to Cuernavaca for Spanish-language instruction,” Scialabba writes, was to “leave Latin American peasants alone, or perhaps even try to learn from them how to de-develop their own societies.” Screwy? Yes. But Illich’s insights are still worth attending to.

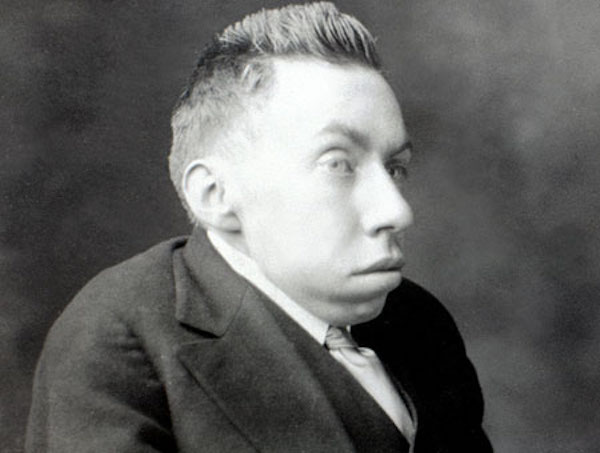

Essayist George Scialabba — a moderate man stranded in immoderate times. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Isaiah Berlin, on the other hand, is the kind of conservative Scialabba doesn’t like, a smooth operator whose forte was telling the establishment exactly what it wanted to hear, but doing so far more skillfully than members could ever do themselves. Scialabba describes Berlin as “a supremely effective exponent of the conventional moral and political wisdom,” adding archly that doing so “with large resources of erudition and eloquence … is an important service.” Berlin is best known as the author of the 1953 essay, “The Hedgehog and the Fox.” But despite writing a not-unsympathetic biography of Marx, he also turned out reams of anti-communist guff that Scialabba quotes at considerable length in another essay just to show how low the great man could stoop. Berlin thus informs us that Marx believed, or at least implied, that “a large number of human beings must be sacrificed and annihilated if the [socialist] ideal is to triumph” and that “the road to the gates of Paradise is necessarily strewn with corpses,” all of which Scialabba rejects as nonsense. The prose may be silky smooth, “but as an account of Marx’s historical materialism, it is tosh,” he says. “…To talk darkly of liquidating half mankind or pulverizing human anthills – that is, to assimilate Marxism to Stalinism – is mere mischief.”

“I do not mean that Berlin has tailored his rhetoric to flatter the prejudices of his Establishment audience, or anything of that sort,” Scialabba adds. “On the contrary, he seems to me all unselfconscious integrity, incapable of altering an adjective, much less an opinion, for the sake of the Erasmus, Lippincott, Agnelli, and Jerusalem prizes altogether” – all of which the much-celebrated Berlin had won. “…But if Berlin didn’t believe and hadn’t frequently and eloquently expounded these damaging half-truths about Marx during the central decades of the Cold War, I doubt he would have been the object of so much institutional affection and gratitude.” This is as vituperative as Scialabba gets. He’s too civilized to give Berlin the old-fashioned boot in the derrière he deserves.

True confession: although Scialabba and I have never met or even spoken on the phone, we’re epistolary friends by virtue of participating in a long-running Marxist listserv that I tried to make as cantankerous as possible. (George did his bit as well.) For that reason, it’s good to discover that he’s as lively as ever and that Only a Voice is filled with provocative arguments that make the reader want to argue right back. His apologia for T.S. Eliot, for instance, strikes this reader as wide of the mark. Yes, Eliot believed in re-distributing the wealth. But so did G.K. Chesterton and other rightists, while Radio Berlin, as George Orwell once noted, was filled with denunciations of British plutocrats even as the Luftwaffe bombed London during World War II. “Distributism,” to use Chesterton’s term, is not inconsistent with fascism, which means that Eliot is hardly off the hook.

But so what? After all, we don’t read Eliot because he was a tame liberal. We read him, rather, because his ideas are spooky, other-worldly, and perverse – not despite their reactionary qualities but because of them. Take the infamous “Bleistein with a Cigar,” published in 1920:

The rats are underneath the piles.

The jew is underneath the lot.

Money in furs. The boatman smiles,

Princess Volupine extends

A meagre, blue-nailed, phthisic hand

To climb the waterstair. Lights, lights,

She entertains Sir Ferdinand

Klein….

This is offensive to all right-thinking people. Yet as an example of right wing post-World War I neurasthenia, it’s as fascinating as it is repellent. Why is Bleistein – “Chicago Semite Viennese” – so threatening in Eliot’s view? What does he portend? What does it say about us that we find him ominous as well? Should we ban poetry like this once the grand and glorious socialist future arrives? Or should we require young people to study it ever more closely so as to better understand the mentality from which fascism arose?

The same goes for Illich. Scialabba says that there’s “nothing quixotic or eccentric” about him because his work “aligns … with what is perhaps the most significant strain of social criticism in our time: the antimodernist radicalism of Lewis Mumford, Christopher Lasch, and Wendell Berry, among others.” But, plainly, Illich is quixotic. That’s the whole point. He thinks that truth has been so thoroughly marginalized by modern society that the fringes are the only place to find it. That’s why he celebrates slums and favelas – because they’re where no respectable thinker would go. Brave as this may be, there’s a flip side worth exploring, i.e. the underlying conservative belief that society is indeed unchangeable and that self-marginalization is the only honorable recourse.

The essays that fill Only a Voice originally appeared between 1984 and 2020. What makes the older ones particularly enjoyable is the way they highlight how conditions have changed. This is a polite way of saying that not all of Scialabba’s opinions have held up. He praises Lawrence for “recogniz[ing] that though the irrational cannot survive, the rational does not suffice.” This is from an article that appeared in the late Boston Phoenix in 1986. What makes it jarring, of course, is that, nearly 40 years later, irrationality is surviving all too nicely while it’s reason that is on the ropes. Rationality may not have sufficed then, but it sure would suffice now. Quoting Christopher Lasch, he complains in a 1991 Dissent magazine essay about public schools pushing “a sanitized, ideologically innocuous curriculum ‘so bland that it puts children to sleep.’” But while the woke ideology that school kids are now spoon-fed can be called many things, bland is not one of them. Scialabba complains in the same essay about “the apathy and gullibility of the contemporary electorate.” But apathetic is the last word to describe today’s deeply pissed-off voters.

The brilliant journalist Randolph Bourne — like him, left wing intellectuals need to concentrate and get to work. Photo: Wiki Common

Scialabba’s celebration of Dwight Macdonald as “an exemplary amateur” seems equally outworn. “To see Macdonald tilting year after year at the political and commercial barbarities of the age, armed with no system but only some peculiar moral and aesthetic intuitions,” he writes, “was – and still is – encouraging.” Really? I’m with Trotsky and his well-known wisecrack: “Every man has a right to be stupid, but Comrade Macdonald abuses the privilege.” To be armed with no system is not to be armed at all. We need more systematic analysis, not less.

Elsewhere in Only a Voice, Scialabba writes of Randolph Bourne, the brilliant journalist who died in 1918 at age 32, that “America’s entry into World War I” – which he opposed – “concentrated his mind wonderfully and provoked the series of furiously eloquent essays for which he is best known today.” World War III is not yet upon us, although the outlines are vaguely discernible. But if that’s really where we’re headed, flitting from one intuition to another is the last thing we need. Rather, we should emulate Bourne and concentrate our minds as well. With the world going to pieces before our very eyes, the first duty of the leftwing intellectual is to roll up his or her sleeves and get to work.

Daniel Lazare is the author of The Frozen Republic and other books about the US Constitution and US policy. He has written for a wide variety of publications including Harper’s and the London Review of Books. He currently writes regularly for the Weekly Worker, a socialist newspaper in London.