Book Review: Annie Ernaux’s “The Young Man” — An Affair to Remember

By Pat Reber

“I was in a dominant position, and I used the weapons of that dominance, whose fragility, in a romantic relationship, I nonetheless recognized.”

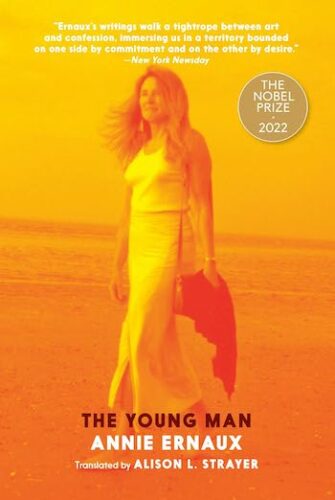

The Young Man by Annie Ernaux. Editions Gallimard, Paris, 2022. English translation by Alison L. Strayer. Seven Stories Press, 60 pages, $8.99.

Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux had put off for 37 years publishing the account of how she survived a horrendous botched illegal abortion in France. One of her best-known books, Happening, finally appeared in French in 2000 and English in 2001, a literary “task” she had long avoided (Arts Fuse commentary).

Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux had put off for 37 years publishing the account of how she survived a horrendous botched illegal abortion in France. One of her best-known books, Happening, finally appeared in French in 2000 and English in 2001, a literary “task” she had long avoided (Arts Fuse commentary).

Ernaux’s newest book to appear in English, The Young Man, surprised this reader with her revelation of how she took on a lover nearly 30 years her junior in order to find the motivation to write that searing personal story about her abortion.

Excavating her past with her usual brutal honesty, Ernaux confesses she believed the fleeting pleasure of orgasm and its let-down afterwards reminded her that her greatest pleasure in life was writing a book. And that she hoped that love-making could be used to help her over her writer’s block. But, looking back, she wonders about the inequity of this belief, particularly when she exploited her status as an established and revered then-54-year-old writer in an affair with a 25-year-old student. Might that be considered an act of cruelty?

Ernaux wrote The Young Man between 1998 and 2000. Now she is 83, and she has decided to publish it via an unusual, almost autobiographical approach. The actual story of her affair with the younger “A.” takes up only 29 pages of this 60-page book. Another nine pages are contemporary photographic portraits of her, ending with an image of shadows holding hands — implying it is her and A.?

Then you arrive at the book’s final 11 pages, where Ernaux offers her life story in brief. It contains yet another surprise — the revelation that the father of her 1963 abortion was a man she would marry a year later, Philippe Ernaux. This is startling because, in her book about the abortion, she only identifies him as P., a man whom she insists at the time she does not love. In these brief notes, Ernaux does not explain what brought about their marriage, which was followed by the birth of the first of their two sons the very next year.

Writers often keep unpublished material in their drawers for various reasons. Is it too personal? Not the right time to publish? Not good enough to publish? To avoid having it found after their death and THEN published?? Did Ernaux write The Young Man out of a guilty conscience while she was writing Happening? Does she have other wonderful texts in her files?

Whatever the case, The Young Man is another opportunity to journey with Ernaux as she peels back an experience, this time one that dates to the mid ’90s. She shivers in A.’s poorly heated student quarters and sleeps on a mattress on the floor. The hot plate and refrigerator lack proper temperature controls. Pasta boils over. Lettuce freezes. She revels in reliving her own student time.

Ernaux is astonished to discover that the window of this chilly abode in Rouen overlooks the now-decommissioned hospital where her life was saved in 1963 from hemorrhaging after a backstreet abortion.

Thus what had begun as a desire on her part for a quick fling with A. “to spark the writing of a book” becomes something more. For Ernaux, the “uncanny coincidence” of the hospital outside A.’s window becomes a sign of “a love story that had to be lived to its fullest.”

She introduces her lover to restaurants and films and takes pleasure in the stares they get, he so young, she in her 50s. “When A.’s face was before me, mine was young too. Men have known this forever, and I saw no reason to deprive myself,” she writes.

Ernaux has written more than a dozen books since the ’70s, drawing from her personal experiences to probe the highly structured nature of French society and its social and cultural prejudices. This is a country where a woman like her, from a working-class family in a small Normandy town, is still regarded as a novelty for having achieved “intellectual gentrification.”

In The Young Man, she grapples with her lover’s own working-class background. She admits that she never would have paid him heed in her own student days, when she was trying to put her class origins behind her. There are resonances with Pygmalion when she writes that she liked to think of herself as the one [emphasis Ernaux’s] who could change A.’s life based on her vast cultural experiences.

She disdains A.’s ambition to avoid working at an ordinary job. Ernaux herself had pursued the teaching profession to support her uncertain path as a writer. While, at times, their age difference seems to narrow, an inevitable gap remains: she has 30 years of historical memory about which he has only faint knowledge — student protests of the ‘60s for example — that cannot be bridged.

As she tries to bring A. into her past experiences, she finds herself imaginatively reliving those times: “He incorporated my past. With him I traveled through all the ages of life, my life.” Ernaux wanted their “story” to be connected with what had gone on before because she had attained enough distance to become herself a “fictional character” within it. Yet she realizes that she placed herself in a controlling position: “That I treated him to trips and saved him from looking for a job that would have made him less available to me seemed a fair arrangement, a good deal, especially since it was I who set the rules. I was in a dominant position, and I used the weapons of that dominance, whose fragility, in a romantic relationship, I nonetheless recognized.”

She is aware that this could be a kind of “cruelty” toward the young man, a kind of “duplicity, ” especially when he expresses his desire to have a child with her. She even seems to consider the possibility despite being post-menopausal.

The relationship continues as she starts working on the book that she had avoided writing for decades, the book that would become Happening. The further she gets into the process, the more she realizes she must abort the relationship with A., “expel him as I’d done with the embryo, more than 30 years earlier.”

In literary circles, Ernaux is proclaimed for having redefined the memoir. In awarding her the Nobel Prize in Literature in December 2022, the committee saluted her “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.”

In The Young Man, Ernaux summarizes this diagnostic impulse in a single sentence on the author’s dedication page: “If I don’t write things down, they haven’t been carried through to completion, they have only been lived.”

Pat Reber, 76, retired journalist living in Maryland, has worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Washington, DC, Germany, Kenya and South Africa. While serving as deputy bureau chief in Washington for Deutsche Presse-Agentur (dpa) during the Bush and Obama years, her reporting beat was climate change. She covered the UN climate talks in Durban (2011) and Paris (2015). She last wrote a review for ArtsFuse on Writing for their Lives: America’s Pioneering Female Science Journalists by Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette.