Film Review: “Chile Año Cero / Chile Year Zero” — After 50 Years, the Fate of Democracy in Chile Remains Uncertain

By Peter Keough

Though the images are half a century old, the chaos, treachery, and courage recorded bear a chilling relevance to circumstances today in our country and in democracies around the world as right-wing efforts to overturn democratically elected governments proliferate.

Chile Año Cero / Chile Year Zero, a film series at the Harvard Film Archive, September 9 through 25.

A scene from Patricio Guzmán’s The Battle of Chile. Photo: Icarus Films

Since 2001, September 11 has lived in infamy as the date on which Al Qaeda terrorists destroyed the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. But 50 years ago on that date another attack, less dramatic in its immediate repercussions but insidious in its lasting impact, occurred in Santiago, Chile. A coup engineered and backed by the CIA and headed by Augusto Pinochet, the commander-in-chief of the country’s armed forces, overthrew the socialist, democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. Pinochet then installed himself as dictator and initiated a reign of terror lasting nearly two decades during which thousands were murdered, imprisoned, or “disappeared.”

These events and those leading up to them are captured with electrifying immediacy and profound comprehension by documentarian Patricio Guzmán in his first trilogy, The Battle of Chile: The Struggle of an Unarmed People. (His second Chilean trilogy, made four decades later, is a masterpiece of poetic imagery, provocative reflection, and wrenching irony). The three older films, in new, 2k restorations, will screen as part of the HFA’s film series Chile Año Cero / Chile Year Zero.

Guzmán, a fervent supporter of Allende who had been filming the rise of the charismatic leader and the crises leading up to his downfall, was himself arrested in the aftermath of the coup and detained with thousands of other political prisoners in a soccer stadium. He was one of the fortunate ones. He managed not only to flee the country but also to smuggle out footage he had shot with breathless urgency and an unfailing eye for the essential and incisive.

Though the images are half a century old, the chaos, treachery, and courage recorded bear a chilling relevance to circumstances today in our country and in democracies around the world as right-wing efforts to overturn democratically elected governments proliferate.

Allende had been elected president in 1970 in a three-way race with less than a majority of the popular vote. Nonetheless, he hoped to put through a revolutionary program of social and economic reforms that panicked the right-wing oligarchs who up to then ruled the country and, more importantly, the US State Department, who saw an Allende administration as providing a foothold for a Marxist takeover of the country, if not the continent. As Richard Nixon’s then National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger put it, “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its people. The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves.” And so the US took up a policy of overt measures, such as economic boycotts and propaganda, and covert dirty tricks, such as training and funding terrorists and plotting assassinations, to undermine the fledgling government.

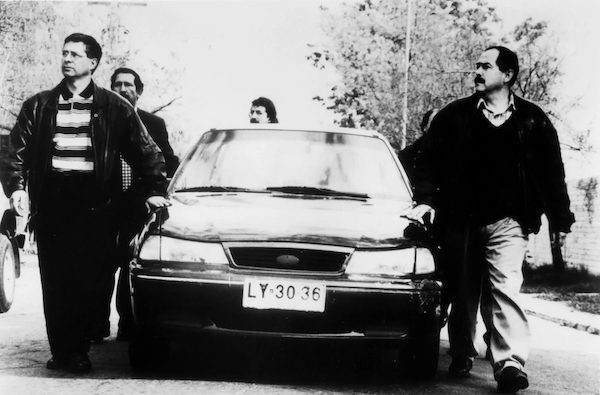

A scene from Patricio Guzmán’s The Insurrection of the Bourgeoisie. Photo: Icarus Films

After the CIA-sponsored murder of General Rene Schneider, Allende’s then head of the army, failed to destabilize the new government, the counterrevolutionary forces resigned themselves for a while to employing constitutional methods to defeat Allende. Part One of the trilogy, The Insurrection of the Bourgeoisie (1975; screens September 9 at 7 p.m. at the HFA) opens on the eve of the parliamentary election of March 1972, in which the opposition hoped to put together a veto-proof coalition of 60 percent or more to block any of Allende’s progressive initiatives.

Wielding an oversized microphone, the bearded, long-haired Guzmán, exuberant and still firm in his faith in the system and the inevitable victory of the working classes, roamed the various demonstrations on the eve of the election to ask random participants for their predictions on the outcome of the voting and the degree to which they supported the president. At one point, true to the film’s subtitle, he barges into a bourgeois apartment where the prim matriarch is all too willing to share her anti-Allende sentiments.

Early returns looked promising for the opposition, but the crowd in the street turned nasty when they failed to gain the necessary super-majority to rein in the President. The anti-Allende faction then orchestrated an obstructionist strategy, encouraging some renegade trade unions in crucial industries to go on strike to destabilize the economy and undermine the government. But most of the workers remained steadfast in support of the leader they elected to fight for their rights and pitched in with ad hoc committees to fill in the gaps when the transportation system and mining operations were threatened. Their inspiring examples of grassroots activism at its best are outlined in Part Three of the trilogy, The Power of the People (1978; screens September 11 at 7 p.m. at the HFA).

Having been rebuffed in these more or less constitutional attempts to eliminate Allende, the right-wing opposition and their CIA backers opted for harsher methods. In June, in the wake of a massive pro-Allende demonstration and perhaps testing whether conditions were right for an all-out revolt, a few military units and a half-dozen tanks attacked the presidential palace in Santiago. The rest of the armed forces stood back and stood by but did not join in. Not this time. These first, tentative mutineers, seeing the time was not right, retreated.

A scene from Patricio Guzmán’s The Power of the People, Part Two. Photo: Icarus Films

In Part One, Guzmán demonstrates his skill at cutting from the dry exposition of speeches and meetings to dramatic, poignant footage of violent conflict. It ends with one of the most disturbing images in political documentaries: the freeze-frame of a soldier in the aborted coup aiming a pistol at the camera lens moments before firing the shot that murdered the cameraman. It is a harbinger of the catastrophe that unfolds in Part Two: The Coup d’état (1976; screens September 10 at 7 p.m. at the Harvard Film Archive).

As a coup seemed inevitable, some of Allende’s supporters objected to his insistence that they remain unarmed and avoid at all costs a bloody civil war. It is an interesting contrast to the situation in the United States now in which all those on the right are equipped with arsenals and threaten an armed uprising. Be that as it may, even after his trusted naval aide-de-camp Commander Arturo Araya Peeters was assassinated, Allende still advocated moderation and tried to appease his opponents (Guzmán’s close-up images of army officers “mourning” at Peeters’s funeral, even then plotting the overthrow of the government, are chilling). He courted the leaders of the Christian Democratic Party, an ostensibly more moderate part of the opposition coalition, and included some members from the right in a cabinet overhaul, including the up-to-now low-key, nominally Constitutionalist General Augusto Pinochet as Commander-in-Chief of the Army.

Meanwhile, his adversaries proved adept at seducing some of Allende’s supporters, raising doubts, and inciting division in their ranks. But most stood firm — though to no avail. Probably the most terrifying image in Part Two is that of the pro-Allende demonstration overwhelming the streets of Santiago on September 4, the third anniversary of his election — nearly a million people chanting “Allende, Allende, el pueblo te defiende!” (“Allende, Allende, the people will defend you!”).

But the supposedly loyal Pinochet had betrayed him. A week after this outpouring of support, Allende lay dead in the smoking ruins of the presidential palace, which had been bombed and stormed by the military he trusted.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).