Book Review: “Virginia’s Sisters: An Anthology of Women’s Writing” — An Inclusive Conversation

By Sylvie Pingeon

By assembling a rich array of poetry and prose by Virginia Woolf’s contemporaries from across the globe, Gabi Reigh honors the famed author’s desire that female writers be named and celebrated.

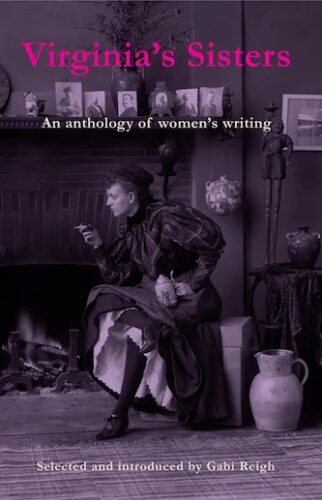

Virginia’s Sisters: An Anthology of Women’s Writing, Aurora Metro Books, 272 pages, $21.99

Editor Gabi Reigh’s introduction to Virginia’s Sisters: An Anthology of Women’s Writing starts off, predictably, with a quote from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own: “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” The female writers in Reigh’s anthology are all named, but the volume’s biographical endnotes reveal that many of them faced considerable, in some cases extreme, consequences — including imprisonment — for penning their words. By assembling a rich array of poetry and prose by Woolf’s contemporaries from across the globe, Reigh honors the famed author’s desire that female writers be named and celebrated. The result is a nuanced, inclusive conversation between female voices made all the more poignant by the fact that it never could have happened in Woolf’s lifetime.

Editor Gabi Reigh’s introduction to Virginia’s Sisters: An Anthology of Women’s Writing starts off, predictably, with a quote from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own: “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” The female writers in Reigh’s anthology are all named, but the volume’s biographical endnotes reveal that many of them faced considerable, in some cases extreme, consequences — including imprisonment — for penning their words. By assembling a rich array of poetry and prose by Woolf’s contemporaries from across the globe, Reigh honors the famed author’s desire that female writers be named and celebrated. The result is a nuanced, inclusive conversation between female voices made all the more poignant by the fact that it never could have happened in Woolf’s lifetime.

Of course, by titling her anthology Virginia’s Sisters, Reigh strategically puts Woolf at its center, no doubt hoping a prominent name will lend gravitas to a lineup that includes lesser-known authors from a wide range of countries, such as China, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Chile, and Israel. Reigh addresses this tactic in her introduction: “How do you persuade publishers to print a translation of a writer whose work, although fresh, daring and beautiful, is largely unknown?” She combines pieces by authors familiar to Anglophone readers (Edith Wharton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman) with texts by unknowns. Reigh has also assembled a rich collection of (mostly female) translators; many of the pieces are translated into English for the first time here. This approach also resonates with Woolf’s dislike of provincialism. In an illuminating video about how the anthology was put together, translator Leilei Chen points out that Woolf, in her lifetime, engaged in conversations with some of the “rediscovered” authors in this anthology. For example, Woolf and Ling Shua, who exchanged letters for years, “are remarkable as [they] dared to express female sensibilities at a time when most Chinese girls were still forced to have their feet bound.” Chen goes onto say that the realism of both Woolf and Shua “endows household objects with explosive meaning and makes [their] writing subversive.”

In addition, the selection of known and unknown voices in Virginia’s Sisters amplifies its themes, as well as its intent to supply nuanced portraits of both women and men in the early 20th century. Reigh opens with a story translated from the Bulgarian, Fani Popova-Mutafava’s “A Woman,” which, as suggested by the title, addresses what it means to be a woman in somewhat universal terms. “This is how a woman comes into the world,” writes Popova-Mutafava. “Greeted with disappointment, resignation and condescension.” In the stories that follow, we are given graphic examples of women moving through male-dominated societies that inevitably greet them with hostility.

The similarities, as well as the striking differences, in these stories and poems allow for some beautiful pairings. Reigh’s modern sensibility shines through in the selection and ordering of pieces. She does more than rely on overarching themes — Reigh is alert to how little details can bond these eclectic works into a cohesive whole. Common motifs, including domestic descriptions of sewing and housekeeping, women traveling alone, and the personification of nature, are used to shape a narrative through-line. The reader is presented with a variety of women in a variety of life stages: some married, some divorced, some single, some young, some old, some gay, some straight and, of course, they are from all over the world. In Woolf’s “The Mark on the Wall” and Dunbar Nelson’s “I Sit and Sew,” women appear in the home. In other pieces, including Katherine Mansfield’s “The Little Governess” and Talmon’s “First Steps,” women are shown traveling. Many of these pieces delve into the complications and power dynamics of heterosexual relationships; others, including Cialante’s “Natalia” and Shuhua’s “Once Upon A Time,” explore homosexuality in places where it was disdained and illegal.

Editor Gabi Reigh

The anthology also includes illustrations that effectively mirror, or sometimes complicate, the stories’ plots. These simple, but attractive, black-and-white prints add dramatic touches to the often sinister narrative themes. In “Villa Myositis,” for example, Gurian describes Li as “imbu[ing] the room with personality, bonhomie and a vaguely tropical scent.” Then, as she slowly removes her aesthetic choices from the room, the protagonist loses herself as well, ending up sickly and isolated. The visuals framing this story beautifully and subtly underline her decline.

Reigh scatters epigraphs throughout the volume from a number of canonized authors: Woolf, of course, but also Jean Rhys, Simone de Beauvoir, and Gertrude Stein. These likely are meant to offer insights into the stories they introduce. It is the editor’s attempt to facilitate conversations among the texts without the intrusion of a modern voice. Notably, most of the authors of the epigraphs do not have any of their work included in the anthology. On the one hand, Reigh has come up with an ingenious way to make more women heard. But at the same time, the epigraphs don’t quite fit: they end up being a little out of place, shoehorned in on occasion. These out-of-context quotes sometimes distract from the anthology’s impact as a succession of powerful voices. Reigh assumes, perhaps a touch presumptuously, that readers will be familiar with female authors who were well known during Woolf’s time period. These female voices, brought in because of their “big” reps, detract from the celebration of lesser-known female authors. Virginia’s Sisters can be easily appreciated and understood without the use of celebrity cameos.

The stories and poems in Virginia’s Sisters are strong enough to stand on their own. This anthology tells a haunting tale of women undermined, manipulated, and used in cultures around the globe. But it also pays homage to the hard work, resilience, and creativity it took to create beauty out of a world of diminished possibilities.

Sylvie Pingeon currently attends Wesleyan University where she studies English and Creative Writing. She is an editor for Wesleyan’s literature magazine, The Lavender, and her work has appeared in the publication Expat Press.

Tagged: Gabi Reigh, Virginia Woolf, Virginia’s Sisters: An Anthology of Women’s Writing, feminist writing