Book Review: Janet Malcolm’s “Still Pictures” — An Anti-Confessional

By Daniel Gewertz

Janet Malcolm never brings up the possibility that her powers of memory have dramatically diminished in old age. If that were the case, such an admission would’ve strengthened the book, giving it context. It would have humanized it, too.

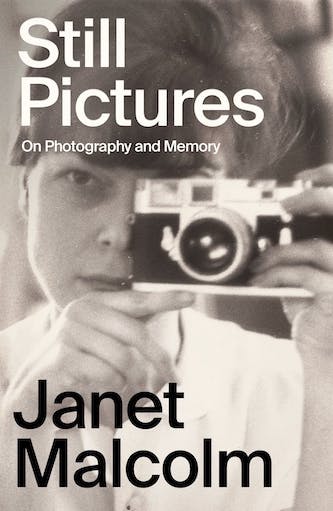

Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory by Janet Malcolm, with an introduction by Ian Frazier, 155 pages. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $26.

Still Pictures, by the late, New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm, is an episodic memoir seemingly at odds with the genre. The quality of her prose runs the gamut from casual to urbane, but throughout the book’s modest length Malcolm shields her emotional life like a wary soldier guarding a castle. This award-winning journalist may have signed a book contract, but she has chosen not to fully embrace the traditional role of memoirist. Beginning with her family’s departure from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, Still Pictures focuses on Malcolm’s formative years in the upper west side of Manhattan. The measured approach might be dubbed an ‘anti-confessional.’

Still Pictures, by the late, New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm, is an episodic memoir seemingly at odds with the genre. The quality of her prose runs the gamut from casual to urbane, but throughout the book’s modest length Malcolm shields her emotional life like a wary soldier guarding a castle. This award-winning journalist may have signed a book contract, but she has chosen not to fully embrace the traditional role of memoirist. Beginning with her family’s departure from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, Still Pictures focuses on Malcolm’s formative years in the upper west side of Manhattan. The measured approach might be dubbed an ‘anti-confessional.’

The book’s subtitle is On Photography and Memory. This is technically accurate. Most of the 26 very short chapters are preceded by a black and white snapshot. But those who come to the book expecting a cerebral take on either photography or memory will be disappointed. The pictures merely serve as jumping off points.

Malcolm died of lung cancer last June at 86. This is her 14th and final book. At first I assumed that these pieces were written very close to the end of her life, with the intention of further drafts. But no. Several were published in the New Yorker as early as 2018. The idea of writing a loosely defined memoir consisting of short takes might’ve been suggested to the famed journalist as a way to pursue a manageable, unintimidating project that needed no extensive research or long interviews. Malcolm could’ve also approached the book as a way to spur an awakening of lost memories. “I have no memory of this” is the book’s most recurring phrase. The photos, the places, even some of the people themselves: all frequent blanks. She never brings up the possibility that her powers of memory have dramatically diminished in old age. If that were the case, such an admission would’ve strengthened the book, giving it context. It would have humanized it, too.

I can imagine long-time fans of Malcolm might be satisfied by the slightness of the project’s scope and its circumspect tone. Yet as thoughtful and well-appointed as some of the prose is, it is often a bloodless memoir. Most memoirists try to create a bond with the reader: call it the art of the personable narrator, or the role of memoirist as a trustworthy friend. I wonder if Malcolm viewed that as a corny conceit.

Malcolm, her younger sister, and her parents escaped Nazi persecution with perilously late timing — the Nazis had already occupied Czechoslovakia months before the family’s departure in July, 1939. Family lore has it that her father bribed an SS officer with the gift of a racehorse in order to receive their exit visas. They crossed the Atlantic not in steerage, but in first class aboard one of the last departing trans-Atlantic civilian ships: a luxury liner no less. “We were among the small number of Jews who escaped the fate of the rest by sheer, dumb luck, as a few random insects escape a poison spray,” she writes. The metaphor is haunting. Yet it’s clear that the luck was not so dumb. Her psychiatrist/neurologist father and lawyer mother were blessed with connections, money, and a savvy intimation of the doom to come.

According to Wikipedia, the family name was originally Weinerová, shortened at first to Weiner, and finally to Winn. (Malcolm is the surname of the author’s first husband.) In New York, young Jana became Janet, and apparently was told they had merely escaped impending European war, not brutal ethnic subjugation. She and her sister were not even told they were Jews. In one of the book’s more striking episodes, young Janet comes home from public-school gaily parroting her Christian schoolmates’ derisive anti-Semitic slurs. It was only then that her father was forced to sit down his two daughters and reveal the heretofore hidden fact: they were Jewish. 100%. With admirable candor, Malcolm admits that her initial reaction was one of shame and anger at her fall from grade-school grace: no longer a member of the in-crowd. There is no further explanation of this childhood identity crisis. (As an after note, she mentions an eventual pride in her Jewish heritage.)

Malcolm proves, on nearly every page, to be the fine sculptor of sentences she always was. She is not a New Yorker favorite of six decades for nothing. Admittedly, the weaker entries seem like mere notes for some future, more focused volume. And yet, she is the same deft writer who dreamed up these devastating lines: “The past is a country that issues no visas. It must be entered illegally.” Or these, in the strong chapter on her father: “We are each of us an endangered species. When we die, our species dies with us.”

My favorite touch was the witty way she ended a bitchy chapter on her boring childhood neighbors, The Traubs, fellow Czech émigrés. After the story goes far afield, a sudden section of “discussion” pops up — written by a highly critical alter ego who takes her to task for her lofty and “repellent” smugness. It’s hilarious.

The way Malcolm repeats “I have no memory of this” can seem a blithe admission, as if the events themselves are to blame. The lapses in memory aren’t just of early childhood, either. In the scant pages devoted to a photo of her family walking the boardwalk of Atlantic City, she not only doesn’t remember being in that resort town at age 15, but has no memory of what must’ve been a spectacular event in her young life: a ride in a small plane from New York City to Atlantic City, N.J. (In the photo she looks like a teen beauty, but Malcolm contends she and her whole family look “terrible.”) Here’s an even more surprising memory loss: When she was nine, a photographer employed by the federal government spent a few days with her family, shooting photos of The Winns enjoying themselves in and around New York City. It was all part of a PR campaign meant to depict how happily Eastern European immigrants can fit into American life. Yet Malcolm claims no memory of the photographer’s multi-day visit.

There are some odd errors. She states that autobiography is a misnamed genre because it isn’t dependent entirely on memory. This is a brain-fogged mix-up that’s begging for an editor’s kind assistance. The word autobiography is derived from the Greek — it denotes a biography written by its subject. No misnaming there. It is clear that Malcolm is getting the word muddled up with memoir, taken from the French, with roots of both memo and memory. Since this chapter first hit print in the New Yorker, it is astonishing it wasn’t corrected. At another point, she exclaims “for crying outside!” when she surely meant the cliché “for crying out loud!”

Mid-book, Malcolm makes it clear she refuses to air complaints about those she respects or loves. About her father she writes: “My mind is filled with lovely, plotless memories of him. The memories with a plot are, of course, the ones that commit the original sin of autobiography. They are the memories of conflict, resentment, blame, self-justification — and it is wrong, unfair, inexcusable to publish them… “‘Who asked you to tarnish my image with your miserable hurts’ the dead person might reasonably ask.”

The fear of her tart-tongue darting its acidy way into print may be the main reason the book avoids emotion. In addition to failing memory, has her fear of bitterness — of being dislikable — infringed upon her confidence? Some childhood cohorts receive both first and last names: an odd and ballsy move. Once she gets into adult life there is barely a mention of lovers, husbands, friends, or co-workers. About her father, she rather slyly lets us know she could complain. This is as far as she will go: “I know he loved my sister and me but he loved his own life more.” A complex thought, simply stated.

Author Janet Malcolm. Photo: Wiki Common.

The occasional aphoristic gem is Malcolm at her best. But to be a memoirist who refuses to make stories out of life is like being a sculptor who refuses to use space.

When I came upon the chapter called “Love Sick,” I thought: Thank God, some real emotion at last! But no: instead it is Malcolm at her most evasive. It begins by offering a group photo about which she cannot even venture a guess. Then she mentions that a boy from high school was an usher at the local Loew’s 72nd Street movie theater. She goes on to describe the theater’s lavish, ornate Arabian Nights decor. The reader now fully expects the aforementioned teenager to enter the picture. But, again, no. After displaying grave discontent that she, like the rest of humanity, has suffered numerous episodes of “chronic longing” and “the virus of love,” she moves onto several pages of analysis concerning Sigmund Freud’s 1915 treatise Observations on Transference-Love. The closest she gets to the emotional tone of memoir here is to add the words “me too” to the millions struck down by the fever of lovesickness. You could call this chapter “the art of the impersonal essay.” Even the most daring chapter, about a long liaison with a married man, is at its most finely tuned when discussing the Manhattan geography of the affair.

The author displays an old world concept of class: if you did not inherit old money you weren’t really rich. The Winn’s upstairs neighbors weren’t rich, she says, they just wound up with two million in the bank by “being frugal.” Malcolm puts down the vast majority of the Czech immigrants of her parents’ generation, who joked often but were never funny, according to the author. (She has stuck fast to some of her teenage prejudices.)

One of the more substantial chapters explains how and why she was sued for libel, lost the trial and then, after extensive coaching, won the appeal years later. (The litigated book was In the Freud Archives.) The fascinating element here is Malcolm’s astute analysis of how her embodiment of the aloof public persona affected by New Yorker magazine writers bedeviled her first trial. “Proved to be dire,” is Malcolm’s phrase. “The idea was to be reticent in real life, self-deprecating and, here and there, funny, but always keeping a low-profile.” On the stand Malcolm chose to be quite above it all. Her instinct in court was to prove she was an excellent writer, and allow the falsity of the charges to subtly come to the fore. “I put myself above the fray; I looked at things from a glacial distance,” she writes. During the trial’s appeal, she dropped the public cool of the New Yorker prototype. She was coached on how to appeal to the jury: how to look, sound, and succinctly prove her case. It worked brilliantly. Malcolm rid herself — on the witness stand — of decades of icy distance.

My contention here is that memoir is akin to public appearance. One is performing for a (friendly) jury of one’s peers. Narrative warmth is called for, but also a true desire to uncover and assemble a series of memories — “plotted” or otherwise — and, if possible, reaccess some of the long gone events in a truthful fashion: to soulfully present yourself to the world. Elegance isn’t enough. Malcolm has previously contended that in long-form journalism, the inclusion of an “I” narrator is but “a construct.. it’s not the person you are. There’s a bit of you in it.” In a memoir, you need more than a bit.

That said, it is my guess that if Malcolm were still alive, she would not allow the publishing of Still Pictures in its current form.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

This seems like a very sad book. Who thought this needed to be actually published?

It was published, as many books are, with the idea of winning back advances from the publisher, and with the family’s hope that she would like it printed posthumously. I’m not at all sure she was a sad case. She had two apparently good marriages, (Her first ended with the death of her spouse.) She also, I assume, was friendly with lots of interesting writers. It is just that she a very poor choice for memoir. I think her fans will tolerate it. I was a bit engaged for a while. She shies away from more than her emotions, but from the majority of interesting meaty, soulful views about life’s episodes.

Dan, I am surprised that such a skilled veteran journalist makes the same writing mistake of many of my students: you save the thesis of your fine essay until the very last sentence If you would have explained from the first that this book by Malcolm was put together after her death by others, and that she might not approve, lots of your problems with the book would be seen in a different, more accurate, light.

I chose not go down the road you suggest for several solid reasons. First off, I have no way of knowing that she would have disliked the publication of her memoirs “in its current form.” It would’ve been pure conjecture, and nothing to hang a long piece on. Yes, it would’ve been a colorful choice, but a flawed one. I will say that the lead I chose was not lily-livered, nor misleading, and was based on the info I knew. Your choice might have also lost some readers right off the bat. I have been a journalist for 40+ years, and I know an intriguing but faulty lead when I see one. (By the way, I’ve also taught memoir writing for decades, and even assigned many adult-ed classes the writing prompt of the old snapshot. It can be done beautifully! I probably didn’t mention my being a writng teacher because I might have sounded didactic and even a touch jealous since Malcolm was one of the most famous journalists in the USA, and, last I checked, I am not.)

So, your idea was simply not my thesis, but an off-shoot of one. I do believe Malcolm would’ve written a bad memoir even if she were healthy, because — about her own life –she is a less than forthcoming writer. It just wouldn’t have been quite as empty. She clearly chose topics that were easy for her to handle, and didn’t reveal too much. It created the picture of a crabby person. She’s a graceful writer, so it was easy to read, and occasionally even a small pleasure. I will admit here that I have not read much Malcolm over the years, and didn’t want to come off an expert.

I never said the book was put together by others. That is not the case. This is what she left. Her daughter wrote a short afterward, and Ian Frazier wrote a love letter of a forward. I would hope, if she had more healthy years, that she would’ve written more. Or trashed the book and tried more of her long-form journalism. Was she dismayed with what she left us? I don’t know. But I do know that the genre of memoir was not a good fit for her.

I will end by saying that my thought about Malcolm’s possible displeasure at seeing the book come to light as it was… it was a thought that popped into my head after days of note-taking, pondering and writing. It wasn’t in my first draft. I love the idea of strong last lines, not simply a summary of the already digested. I was depressed at the thought that this slim book was the best she had to give.

Thank you for this very helpful review. I found the book tantalizing and frustrating but couldn’t quite explain why. Your take on it makes sense to me.

Thank you for your comment. That you have read the Malcolm book — and been left understandably perplexed — makes your pleased response to my (overly long!) review especially welcome. It made my day.