Book Review: “Run Towards the Danger” — Grappling With Memories of Trauma

By Helen Epstein

Sarah Polley’s essay on sexual assault by itself is worth the price of the book, essential reading for anyone interested in the physical and psychological aftereffects of violence against women.

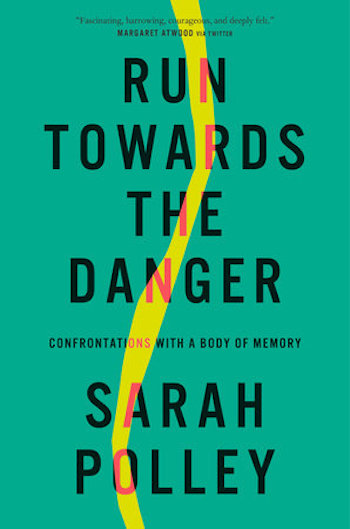

Run Towards the Danger: Conversations With a Body of Memory by Sarah Polley, Penguin Press, 192 pp.

Sarah Polley has been on our cultural radar most recently as the director of Women Talking (Arts Fuse review), but she has had an extraordinarily long and idiosyncratic career, beginning as a five-year old child actor in Toronto. At eight, she worked as Ramona in the TV series adapted from the books of Beverly Cleary. At nine, she starred in Terry Gilliam’s film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. When she was 11, her mother died of cancer. Sarah lived alone with her bereaved father for a couple of years, then with a boyfriend. She continued to work in film, and was widely admired for her performance, at 14, in Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter. Then, as a writer and director, she made the feature films Away From Her (adapted from a story by Alice Munro) and Take This Waltz, as well as the documentary Stories We Tell. She was barely 30, when she created this award-winning Rashomon-like documentary narrated by a group that included the father she knew, the biological father she discovered as a teenager, her four half-siblings, and assorted witnesses.

These films flit through Run Towards the Danger, a collection of six autobiographical essays about traumatic events and how she remembers them now that she is in her early 40s. During that time, Polley became a political activist, a wife, mother of three children, and friend and colleague to dozens of people — famous and not — who appear and reappear in these essays. Polley is quintessentially Canadian in her graciousness toward all of them and in her understated approach to memoir. “These stories don’t add up to a portrait of a life, or even a snapshot of one,” she writes in her preface to the essays, some of which she has been thinking about for decades. “They are about the transformative power of an ever-evolving relationship to memory. Telling them is a form of running towards the danger.”

That motto — “Run Towards the Danger” — is the advice a Pittsburgh neurologist gave Polley after a fire extinguisher fell on her head in 2015, resulting in years of post-concussive syndrome. Unlike all the other physicians she consulted, he believed that “in order for my brain to recover from a traumatic injury, I had to retrain it to strength by charging toward the very activities that triggered my symptoms.” In this theme-driven book, Polley addresses experiences of physical and psychological traumatic injury, and the conclusions she draws from those repeated confrontations now.

Polley’s first memoir is as idiosyncratic as her films. She eschews a clear narrative arc and instead willfully digresses over long swaths of time and subject, following her associations as one does in psychoanalytic therapy. As in Stories We Tell, she relies heavily on the input of other people for her story line. All her chapters are set in Canada, and each deals with one traumatic situation in depth, reconsidered multiple times over many years.

The first and most intricate chapter is “Alice Collapsing,” set at the Stratford Festival’s staging of Alice Through the Looking Glass in the summer of 1994, when Sarah was 15 and cast as Alice. It addresses her theater debut, rehearsing and performing, while the scoliosis with which she was born becomes ever more painful. Polley has strong feelings and theories about the relationship between Alice Liddell (the model for Alice) and Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll), but she’s unable to persuade her director to allow her to probe them during the production. Instead, the production has one objective: to “delight” children. She speculates about Dodgson’s pedophilia and her own ambiguous relationship to her father. She also describes the practical ways of compensating for a crooked spine while performing, as well as the conflation of physical and psychological pain that, in her case, resulted in paralyzing stage fright. The essay is strewn with quotes from Alice in Wonderland and reads as though it’s bursting at the seams. There is enough material here for a novel and it could use several rewrites. I gave up twice and moved on to the other essays. Only when I circled back was I able to make more sense of this fascinating but not fully digested text.

“Mad Genius” is perhaps the most conventional chapter in that it is a reflection on the process of making a movie. Polley’s spin on this material is looking back on what it was like to work as a child actor under the direction of Monty Python’s Terry Gilliam in 1987. Monty Python had been a beloved part of the Polley family culture: both her parents were avid fans. In kindergarten she startled her teachers by singing, “I love to hear you oralize when I’m between your thighs you blow me away.” When she won the part of Sally Salt in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, she writes, “I witnessed in my father a pure unmitigated elation.… the pinnacle of my success and my father’s pride had been reached. I was eight years old.” The family moved to Italy (for filming in Cinecittà) and then to Spain. Chaos and near-fatal accidents with explosives ensue. Sarah is left with lifelong PTSD, ducking when she hears a sudden noise. Years later, after Gilliam made controversial remarks online about the #MeToo movement, his carelessness in directing then-child Sarah Polley was recalled. Her costar Eric Idle tweeted, “She was in danger. Many times.” In 2018, more than 30 years after the filming, Polley writes gratefully, “Someone who was there was appearing out of nowhere to confirm my memories and verify my version of events.”

The importance of a witness to validate traumatic memory is nowhere more evident than in “The Woman Who Stayed Silent.” This compelling chapter alone is worth the price of the book: a long, unsparing examination of Polley’s own nearly three-decade-long silence regarding an experience of sexual assault at the hands of Jian Ghomeshi, host and co-creator of a popular CBC talk show. It happened in the early ’90s, at a time when Harvey Weinstein was blithely locking in NDAs from actresses he had assaulted while receiving over-the-top expressions of thanks from them at Oscar speeches. It was also long before reporters Jodi Kantor, Megan Twohey, and Ronan Farrow documented the story in 2017 and #MeToo hit the internet.

Polley’s quiet and self-contained essay moves from the ’90s to 2017, zeroing in on her flickering memories of assault, her reluctance to speak about it, her examination of that reluctance, her interrogation of other women in her situation, of lawyers, and her thoughts about all of it now. She is not a journalist and is not interested in providing a summary of what most of her Canadian readers already know, so here’s my American one:

Jian Ghomeshi was a hip, attractive CBC employee, more like a younger, feminist, Iranian-Canadian version of intellectual talk show host Charlie Rose than a Harvey Weinstein. Starting in 2007, when he was 40, Ghomeshi hosted a talk show called Q, airing twice daily on the CBC, and in the US. Though a nationally known figure, he lived and worked in the small cultural community of Toronto, where almost everyone knew him or knew someone who knew him. His and Polley’s paths had already crossed casually when he was performing with a Toronto band.

Polley’s essay begins as she discovers a tweet about herself online: “Wonder why Sarah Polley never spoke out about being assaulted by Jian Ghomeshi. #HerToo. She was the woman who stayed silent. Ask her.” No one had “liked” or retweeted the post, she notes, but it rattled her and made her resolve to try once again to write what she had resisted writing for years.

Polley first met Ghomeshi directly at a party when she was a teenager. She wonders if her story should begin “twenty nine years ago, when I was around fourteen years old, and a man in his twenties tenderly brushed a strand of hair away from my face,” or two years later, when “something happened to me that I couldn’t understand, and so part of my brain hid it from me until years later.” She decides to start at the age of 35, when in the summer of 2014 her friend, freelance writer Jesse Brown, tells her he is reporting on four women who have accused Ghomeishi of sexual assault. He is set on pursuing the story but doesn’t know how best to do it while protecting himself from legal action.

Why does he ask her? She is a filmmaker, not a lawyer, not a reporter, not even a memoirist at that point. Polley doesn’t explain. In fact, she spends little time establishing the context of what will become Canada’s most explosive media story of sexual assault. Nor does she raise key questions most nonfiction writers would identify and answer. Instead, Polley deliberately chooses to carefully lay out the predicament and thought process of an insider, one of the women whom Ghomeshi has “allegedly” (she puts the term in quotes for legal reasons) assaulted — in her case, as a minor. She follows the advice of her lawyer brother and her lawyer friends not to “come forward” and testify in court, but to bear witness as a memoirist. Her brother instructs her to write down every detail she remembers and finds relevant to the process of moving from silence to speech. Her achievement, I think, is significant and worthy of its own film. Nonetheless, I felt a need for more context and did some research.

Author and filmmaker Sarah Polley. Photo: Twitter

By the fall of 2014 most of Toronto’s close-knit media community had been hearing rumors about Ghomeshi for years. Some insiders knew that Q’s female producer had complained to her union that Ghomeshi had sexually and emotionally harassed her for three years. Some were aware that journalism students at the University of Western Ontario were no longer allowed to apply for internships at Q because of Ghomeshi’s inappropriate behavior. Some knew that Ghomeishi had told his CBC superiors that an ex-girlfriend was alleging he raped her and that the CBC had hired a crisis management team. Some knew that yet other women had complained about Ghomeishi and had been harassed on the internet. In December, the New York Times op-ed page ran a story about them.

But Ghomeishi was, like his American counterparts, defiant and, as a successful minority media darling, all but untouchable. A profile in the glossy Toronto Life earlier that year gushed that his show was syndicated by 160 US stations; a weekly televised version drew 300,000 viewers; the Q YouTube channel averaged 1.5 million hits per month; the podcast, about 250,000 downloads a week. His memoir, 1982, was number one on the bestseller lists when it was published in 2012.

Faced with this situation, Polley’s friend Jesse Brown tried to find institutional support. By the summer of 2014 he got it from the Toronto Star and one of its investigative reporters, Kevin Donovan. In October, Brown tweeted that he was working on a story that would be “worse than embarrassing for certain parties.” As Donovan reports in his 2017 book Secret Life: The Jian Ghomeshi Investigation, Ghomeshi’s legal team invited CBC executives to watch X-rated videos from the host’s private collection in an attempt to persuade them that Ghomeshi was no assaulter, just a guy into rough but consensual sex. They miscalculated. The CBC fired Ghomeshi and the Star published a long, widely publicized report. By November, more than 20 women alleged Ghomeshi had slapped, hit, punched, choked, or bitten them during sex, beginning in 1988. A Royal Canadian Air Force captain named Lucy DeCoutere was first to go on record and inspired the hashtag #IBelieveLucy. Ghomeshi was arrested and his trial set for February 2016.

In Run Towards The Danger, Polley keeps her narrative focused on her small, then private thread in this saga. “In the days following the Toronto Star story,” she writes, “more women came forward with similar stories including actor and Canadian Air Force captain Lucy DeCoutere, who was the first to identify herself publicly…. she encouraged other women to come forward and to tell their stories and to share their names if they could.”

Polley could not. In her polite, understated narrative, she points out that in October of 2014, she was married and had two children under three, one breast-feeding. She does not remind us that she was still suffering from postconcussive symptoms from the fire extinguisher episode. She does not say what she told her husband or her therapist. But she does describe her discussions with other Ghomeshi victims, with her siblings, and with friends. When she tells her older sister Jo she feels lucky that Jian didn’t choke her, Jo surprises her by replying, “But he did choke you, didn’t he?” It is only when her lawyer brother Mark recalls picking her up after her date with Ghomeshi that Polley starts to remember.

For years she had been dining out on the story of her “worst date ever,” but left out her age (16) and his (28). She left out what exactly had happened during sex, how she had told only pieces of what happened to her brother and sister, and how she had appeared on Q — friendly, self-deprecating, ingratiating — when publicity for her films had required it. She also maintained a friendly, flirty email correspondence with him. For the next few years, she asked many people whether or not she should “come forward.” Her brother and almost all the other lawyers she consulted told her not to. Too many people had heard that milder, less violent version of the encounter at dinner parties. Some of them were lawyers. She would be skewered. “Recovered memory” was suspect.

Ben Whishaw, Rooney Mara, and Claire Foy in scene from Sarah Polley’s film Women Talking.

Only a few people disagreed with the majority. “The advice you get from lawyers,” one friend told her, “isn’t necessarily going to be the same that you will give yourself as a woman, as a mother, as a political activist.” Only one criminal lawyer advised her to come forward and say everything and be clear that what happened was a sexual assault. “It was the right thing to do, he said.”

Polley decided to keep quiet. She does not mention reading the many articles in the Canadian press about Ghomeshi and/or sexual assault, or Kevin Donovan’s book. Her focus remains on the evolution of her thinking. She begins to make sense of her own cringe-worthy behavior. She explains her decision not to go public to a friend who had worked at the CBC, and quotes her as saying, “I think that at some point your moral compass is going to kick in and you won’t have a choice about what to do.”

The eight-day trial before a judge — no jury — took place in February 2016. Some of the allegations dated back a decade. Canadian weekly MacLean’s wrote that two courts — the criminal justice system and the court of public opinion — collided with brute force on the morning of March 24. Justice William B. Horkins acquitted the former CBC Radio host on four charges of sexual assault and one count of overcoming resistance by choking. The judge’s plainly worded decision was unsparing in describing the three complainants’ lack of reliability and credibility: they were “deceptive,” “manipulative” and showed “a wilful carelessness with the truth,” he said. If a hashtag had been attached, it would have read: #IDoNotBelieveThem.

Sarah Polley does not tell the reader how much of this she followed or how it influenced her decision to ultimately write her own book about trauma, which includes her own belated testimony in the Ghomeshi case. I, for one, am grateful that she did it in her own time and her own way. Her essay deserves to become a classic, of interest not only to memoirists but to all those who are interested in the aftereffects of violence against women.

Helen Epstein is the author of the memoir The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma, Getting Through It and nine other books of literary non-fiction.