Film Review: “Frownland” — An Invisible Person Made Intimately Visible

By Betsy Sherman

This little-seen film — disturbing, uncompromising, often darkly funny — should be recognized as one of the most original American independent films of this century.

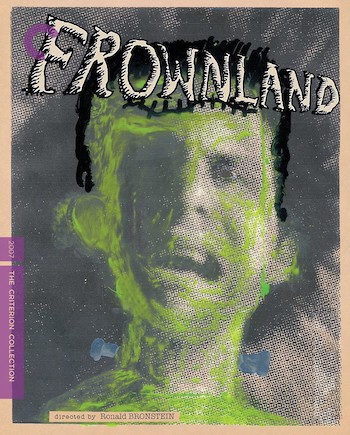

Frownland – Directed by Ronald Bronstein. Available on Blu-ray and DVD from The Criterion Collection, and streaming at criterionchannel.com.

While New York City was experiencing its travails of the early-to-mid-2000s, both monumental (the September 11th attack) and incremental (the Disney takeover of Times Square and other such gentrification), a creative project was slowly taking shape within its borders. Ronald Bronstein’s debut feature Frownland (2007), a no-budget movie made over six years, was an illustration that, in the great city’s underbelly, qualities such as pride and resilience were not within reach of everyone. The little-seen film should be recognized as one of the most original American independent films of this century.

While New York City was experiencing its travails of the early-to-mid-2000s, both monumental (the September 11th attack) and incremental (the Disney takeover of Times Square and other such gentrification), a creative project was slowly taking shape within its borders. Ronald Bronstein’s debut feature Frownland (2007), a no-budget movie made over six years, was an illustration that, in the great city’s underbelly, qualities such as pride and resilience were not within reach of everyone. The little-seen film should be recognized as one of the most original American independent films of this century.

Frownland played some film festivals and had assorted screenings, but never got nationwide distribution. I attended a memorable screening at the Harvard Film Archive on Sunday, July 8, 2007, at which Bronstein and star Dore Mann presented the film. It has drifted back into my consciousness now and then, with an attendant bewilderment about why this feverish little gem seems to have been forgotten. No more need to fret — it’s been released by The Criterion Collection with a director-supervised remastering on Blu-ray and DVD, and with engaging extras that illuminate Bronstein’s disturbing, uncompromising, often darkly funny work.

With its title taken from a Captain Beefheart song, and an undertow it shares with fiction by Kafka and Dostoyevsky, Frownland is a character study like few seen in American cinema. The film’s intention is not to get viewers from story point A to B to C. It isn’t only that puzzle pieces are missing: the pieces change shape when you’re not looking. What counts is how what you’re seeing and hearing makes you feel. Frownland succeeds in its mission: making intimately visible an invisible person.

Keith Sontag is barely scraping by in a world that, if it notices him at all, gives him the cold shoulder (Dore Mann gives a brave, raw performance, heading a cast of fellow nonprofessional actors). He’s stuck in barely tolerable living conditions, has a demoralizing job, a hideous roommate, and disturbing family memories. The movie opens on him lying on a bed that’s crowded into an apartment kitchen, eating popcorn and watching a monster movie. Keith is completely contented, and this is the last time we’ll see him anywhere near that. The doorbell sounds, all that comes through the intercom is the sound of sobbing — and we’re off to the races.

Keith knows exactly who it is, a young woman named Laura (Mary Wall, another fearless performer). Her relationship with Keith is enigmatic; we don’t know what the sobbing is about, or whether he had anything to do with it. Keith tries to at least make a show of empathy, pulling at the skin around his eyes to produce water from his tear ducts (recalling D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms, in which abused waif Lillian Gish has to push the corners of her mouth up in order to present a smile). We later find out that Mary is a high school student with a propensity for self-harm, and suicidal fantasies expressed in the comics she draws. In this early part of the film, her masochism is demonstrated by burying her face in a down pillow that she knows will make her skin break out.

Keith exists in a sort of prison; the movie leaves it up to the viewer to decide whether it’s one of his own making. He’s crowded into the film frame, as cinematographer Sean Williams practically glues the camera to Mann’s face. Keith takes self-effacement to an extreme: his verbal communications are prefaced by apologies, qualifiers, and aptly chosen (so he thinks) analogies. Rather than entryways into a conversation, these embellishments are just houses of straw, easily blown down by the big bad wolves he encounters. Whether this should be seen as an affliction or not (Keith does see a psychiatrist), this locution is used by the movie as simultaneously a source of uncomfortable humor and an acknowledgment of his suffering.

Then there’s his job, going door to door selling coupon books said to benefit a multiple sclerosis charity. To make the task harder, the crew of hawkers is dropped off in communities where soliciting is forbidden. Keith’s sense of failure is visually underlined in the exchanges with his boss Carmine (Carmine Marino), the supplicant Keith on the pavement, the unreceptive Carmine in the driver’s seat of the van.

Another figure in Keith’s orbit, perhaps not by choice, is Sandy (David Sandholm). No backstory is given to their friendship, but we can glean from shots of him closing up a bar that he may be a bartender, and feel that profession’s duty to listen to the troubles of others. He tolerates Keith’s presence and can absorb his idiosyncrasies, up to a point.

The most fraught, and painfully entertaining, scenes in Frownland are those in which Keith confronts his roommate Charles (played with delightful effeteness by Paul Grimstad, who also scored the film’s sometimes whimsical, often creepy, synthesizer score). While Keith sleeps in the kitchen, Charles gets to spread out in the main living space, which contains his electric keyboard. The situation that’s coming to a head is that Charles hasn’t paid the electric bill and a service cut-off is imminent. Think of every similar situation you’ve had like this, then raise it to its maximum degree of awkwardness and pressure. Charles is as facile with words as Keith is tongue-tied. His taunts, not to mention his superior tone, are cruel, but his description of Keith’s “ridiculous, disjointed splutterings” is pretty accurate, as Keith himself might admit. The manner in which Charles says he’ll take care of the bill throws the likelihood of that happening into doubt, and makes Keith very, very nervous.

Keith (Dore Mann) as the desperate salesman in Frownland.

This magnification of a banal incident into high drama may seem a stretch, but it works. Keith’s desperation escalates, especially after a subsequent fight with Charles (by candlelight). Propelled down the city streets at night, Keith becomes manic, striding furiously forward, a broken cigarette in his mouth. The eerie synthesizer music ramps up, and the grainy cinematography (shot using a short-lived Kodak 16mm film stock) makes it look like, as Bronstein describes it, the actor is surrounded by “a swarm of angry bees.” Perhaps inevitably, the movie circles back to its monster-movie opening, with Keith besieged by a hipster version of villagers with torches.

Frownland stands as Bronstein’s only directorial feature. In the years since, he has been working with (Boston University’s own) Safdie brothers (Good Time, Uncut Gems) as a co-writer and editor, and also as star of their 2009 Daddy Longlegs.

The Criterion disc extras are choice. There are two deleted scenes, the more interesting one being an extension of Keith’s visit to a psychiatrist. The setup for Bronstein’s 35-minute conversation with Josh Safdie is in keeping with the dark-comic tenor of Frownland: Safdie was dragged in by Bronstein to shoot the piece even though he had a 103-degree fever. It’s a fabulous rundown of what led to Frownland, what it was like making it, and Bronstein’s outlook on the world.

Plus there’s a booklet that perfectly reproduces the look and feel of a fanzine. Inside, there’s a sharp essay by Richard Brody and a valuable oral history of the film compiled by Michael Chaiken. Director, cast, and crew members discuss the technical, creative, and perhaps most of all, psychic challenges of being part of their collective. Just a taste: as part of the extensive rehearsal process, Bronstein had Paul Grimstad go to East Village bars in character as Charles and “be a dick to people.” He had Dore Mann, in character as Keith, interact with women in AOL chat rooms (“That went as well as you might imagine,” says Mann).

A recurrent note struck by Bronstein is his disdain for exposition (says actress Mary Wall, “He’d much rather have people not know what’s going on”). In the conversation with Safdie, Bronstein criticizes the urge to “orient” audiences with introductions or explanatory opening sequences, which he calls “essentially lubricating them into the right frequency to feel that they’re in good hands.”

So watch Frownland (without looking at the extras first!). If you believe that part of the mission of art is to dis-orient you, you couldn’t be in better hands.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.