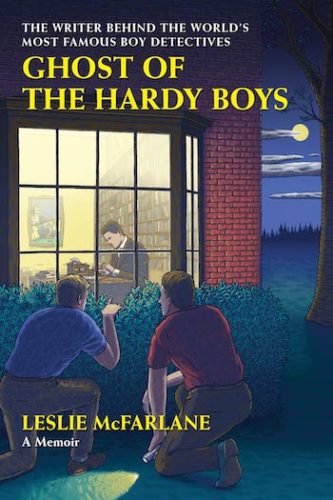

Book Review: “Ghost of the Hardy Boys” — The Man Behind America’s Favorite Teenage Sleuths

By Gerald Peary

In this genial, colorful memoir, Leslie McFarlane reveals the long path to how, anonymously, he became author of the best-selling series of boys’ books in publishing history, 20 million volumes and counting.

Ghost of the Hardy Boys by Leslie McFarlane. Godine, 304 pages, $24.95.

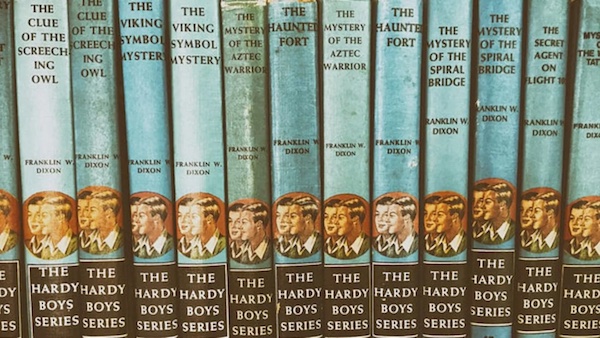

As a Hardy Boys-crazed lad of seven and eight, page-turning madly through a half-dozen of their mysteries, I also had, I suppose, a first favorite author. Franklin W. Dixon. I knew the name for sure, but I don’t recall any curiosity about who exactly that was. If I had vague thoughts about him, there was a conflation in my mind with how I pictured Frank and Joe’s tweedy detective dad, the venerable Fenton Hardy.

As a Hardy Boys-crazed lad of seven and eight, page-turning madly through a half-dozen of their mysteries, I also had, I suppose, a first favorite author. Franklin W. Dixon. I knew the name for sure, but I don’t recall any curiosity about who exactly that was. If I had vague thoughts about him, there was a conflation in my mind with how I pictured Frank and Joe’s tweedy detective dad, the venerable Fenton Hardy.

As an adult, I’ve known for decades that “Franklin W. Dixon” was a nom de plume. But of whom? Seventy years after my Hardy Boys childhood, lazy me finally bothered to locate the answer, which has been available to those who cared to know for at least 45 years. It’s all laid out in Leslie McFarlane’s colorful, genial memoir, Ghost of the Hardy Boys, first published in 1976, a year before McFarlane’s death. (The book has been reissued in hardback by Godine with a nifty faux Grosset & Dunlap 1920s Hardy Boys cover.) Therein, McFarlane reveals the long path to how, anonymously, he became author of the best-selling series of boys’ books in publishing history, 20 million volumes and counting.

It began in the mid-’20s when McFarlane, already a veteran journalist in northern Ontario, took, for adventure, a newspaper job in the United States. He expected tabloid excitement when he went to work for the Springfield Republican in Western Massachusetts. What he discovered was a gentlemanly, leisurely paper which actually had a policy against “scoops.” McFarland defied company protocol by coming in one day with an inside interview of a passing-through theater personality. Good stuff? The editor informed his eager reporter that the celeb had already been interviewed in the Republican seven times through the years, and he told exactly the same stories.

Bored and unchallenged, McFarlane looked about for something fertile to do in his Springfield off hours. Fortuitously, he answered a cryptic ad in Editor and Publisher asking for “Experienced Fiction Writer Wanted to Work from Publisher’s Outlines.” Soon after, he got a letter from a certain Edward Stratemeyer in East Orange, New Jersey, offering him a chance to audition for Stratemeyer’s syndicate. Little did McFarlane know that this was “the Henry Ford of fiction for boys and girls.” Stratemeyer was the person behind an extraordinary assembly line of juvenilia that flooded America from the beginning of the 20th century, including (among many other series) the Rover Boys, the Bobbsey Twins, Bomba the Jungle Boy, and Nancy Drew. Stratemeyer himself wrote some of the books, including ghosting posthumous Horatio Algers. But mostly the writers were for-hire employees assigned company-produced pen names, authoring books that rigorously followed plot outlines provided by Stratemeyer. You got $100 for each completed book, but, contractually, no royalties or name recognition ever.

Said McFarlane of Stratemeyer: “Many of his writers were professionals. Some of them … were actually very well known to the American public. When they wrote for Mr. Stratemeyer, however, their identities were hidden behind ‘house names’ which belonged to the syndicate.” Next to his meager income for the Republican, McFarlane thought that $100 for a quickly written book wasn’t a bad deal. He passed the entry test for Stratemeyer, writing several chapters of a proposed novel from an outline; soon he found himself employed writing the sixth book in a series about the deep-sea diver Dave Fearless. McFarlane shed his own name for that of author Roy Rockwood, who, he found out, was supposedly responsible also for the Bomba the Jungle Boy series. “Now I learned from an unimpeachable source that Roy Rockwood wasn’t a human being at all. He didn’t exist; he never had existed. He was just as fictional as Bomba.”

A young Leslie McFarlane. Photo: Godine

And so it was that McFarlane as Rockwood came to pen Dave Fearless Under the Ocean. Stratemeyer wrote back that it was “a lively narrative,” and assigned McFarlane more Fearless volumes. “He wanted to know if I would take an assignment every month and make myself available for other series.” McFarlane agreed to the bargain and, while working on Dave Fearless in the Black Jungle, resigned from his job at the Republican. He moved back to Canada, living by himself in a cabin in Northern Ontario. He would write whatever was assigned to him by Stratemeyer, and he might still have time left over to pursue a career in serious fiction. He’d been admiring stories by Joseph Conrad in H.L. Mencken’s The Smart Set, and Conrad would be his literary model.

However, his Heart of Darkness never came. A story he was proud of writing about a brother who discovers his sister when he visits a whore house was submitted to Mencken with hope for publication. This was the wonderful one-word rejection: “Naïve. HLM.”

But McFarlane was consoled by Stratemeyer asking if he’d like to do the first three books initiating a detective series. Hopefully, the Hardy Boys could match the success for children that the S.S. Van Dine Philo Vance books had achieved for adults. And there would be a higher price for providing each book: $125. McFarlane accepted immediately. “What a change from Dave Fearless! No man-eating sharks. No octopi. No cannibals, polar bears or man-eating trees.” Just two two high-school students, brothers Frank and Joe Hardy, who were obsessive amateur detectives. But lest the reader get any idea that the new series offered artistic freedom: it was Stratemeyer who came up with all the characters, down to Chet Morton and Biff Cooper, and he also invented the hometown setting, the small city of Bayport on Barnet Bay, on the Atlantic Coast. Stratemeyer provided the book’s title, The Tower Treasure, and all subsequent titles.

Stratemeyer gave McFarlane his new author name: Franklin W. Dixon.

Starting in 1927, McFarlane was to write over the years 21 Hardy Boys books, including my two childhood favorites, The Missing Chums and The Secret Panel. In his memoir, he seemed more bemused by their existence than deeply proud of them. They certainly never gave him a big head. But he was proud of his professionalism carrying through his assignments, which he considered a major step up from the total hack work of Dave Fearless. He acknowledged special touches that he brought to the series, like spending time on the meals the Hardy family ate, or his vivid characterization of their cantankerous Aunt Gertrude, who became, to everyone’s surprise, the favorite character of readers. McFarlane admitted he failed with the Hardy mother, Laura, whom he labeled as “bland” and never more than “a carrier of sandwiches.”

McFarland did manage in his lifetime (1902-1977) to publish lots of genre fiction. But he really made a second career in Canada as a film documentarian and then a mover-and-shaker in network television production. At home, he kept a shelf of his Hardy Boys books, seemingly never opening them for a nostalgic read. His son wasn’t even told that he’d written them. Curiously, he never met Edward Stratemeyer in person, nor did they ever once commiserate on the phone. But he thought fondly of his legendary editor, always grateful to have gotten the chance to write those books, and apparently not minding at all that, though so many millions of Hardy Boys were sold, Leslie McFarlane made a grand total of about $15,000 as Franklin W. Dixon.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque; and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world.

Tagged: Gerald Peary, Ghost of the Hardy Boys, Godine, Leslie McFarlane.

If McFarlane said that Stratemeyer was in East Orange, NJ in 1926, he was mistaken. Edward lived in the Roseville section of Newark from 1907 until his death in 1930. From the fall of 1914 he conducted his business from offices in New York City in the vicinity of Madison Square Park. There were a sequence of these as the offices became unusable when tall buildings around blocked the natural light coming through the windows.

Further, the ad that McFarlane responded to was not in Editor and Publisher. That was a trade magazine of the era but no Stratemeyer ad appeared in it. However, his ad DOES appear in The Editor of April 10, 1926 (p. 17) with different working than McFarlane remembered.

McFarlane was writing of events half a century before the book was published in 1976. It is natural that he would have some lapses of memory. But some of the items are made up or exaggerated for dramatic effect under the influence of his editor at Methuen. It is simply not possible to treat this book (new or old edition) as an historical record. I wish that the new edition had footnotes to mark his departures from reality. It is very glib and humorous but nothing can be taken at face value unless it is corroborated from a contemporary source such as a letter from the Stratemeyer Syndicate Records Collection at NYPL.

For example, he talks about being excited to write as “Roy Rockwood” since he had read Bomba the Jungle boy in his youth. The trouble with this is that McFarlane was born in 1902. Bomba started in 1926, the same year he started writing Dave Fearless stories for Stratemeyer (volumes 10-15).

Other Stratemeyer issues can be discovered on my Stratemeyer.org website. It is a topic of interest of mine for more than 33 years and I have several books in the works related to them and series books in general.

Who would have known that there was a genuine Edward Stratemeyer expert in the house peering over my shoulder? Yes, I took McFarlane at his word about the details of his life and he, honest chap, was remembering to the best of his ability what happened half a century earlier. Can you forgive him for saying he read an ad in Editor and Publisher when the actual ad was in The Editor? Can anyone really trust his/her memory? If McFarlane recalls his childhood love of Bomba the Jungle Boy books when the series didn’t even exist, maybe I never read a Hardy Boy book as a child and only thought I did! Those who read my review above should proceed with skepticism and caution.

Gerald, I enjoyed both your article and your response to perhaps the only expert in the world on Edward Stratemeyer. BTW, I received the Hardy Boys tomes as a boy as hand-me-downs from my older cousins. I enjoyed the Bobbsey Twins books from my public school library in the second grade. The only thing that I might have added to your entertaining piece was that the $125 fee in 1927 is equal to about $2000 today.