Book Review: “The Poetics of Cruising” — Imaginative Acts of Capture

By Nicole Veneto

By exploring the historical and artistic significance of cruising throughout poetry, photography, and visual culture, the book produces a rich and exciting topography of queer culture that posits a reflexive relationship of vicarious cruising between “cruising texts” and their consumers.

The Poetics of Cruising: Queer Visual Culture from Whitman to Grindr by Jack Parlett. University of Minnesota Press, 256 pages, $27 (paperback).

What’s in a look? Is a chance meeting with the eyes of a passing stranger on the street as consequential as a long, desirous gaze at a potential hookup on the other side of the bar? How do we derive meaning from looking and being looked at by other people? What sort of powers are at play between the one who looks and the subject of that look, who may or may not be aware that they’ve been pierced by a glance? The social, political, and cultural dynamics that govern seeing and being seen are the backbone of queer and feminist media studies. As a media theorist myself, discourses over voyeurism, spectatorship, and (un)reciprocated gazes make up a bulk of what I’ve studied throughout my academic career. Looking is how we perceive and construct images of others, and what goes into that perception is as reliant upon our own subjective interpretation as it is on how others are visually represented.

What’s in a look? Is a chance meeting with the eyes of a passing stranger on the street as consequential as a long, desirous gaze at a potential hookup on the other side of the bar? How do we derive meaning from looking and being looked at by other people? What sort of powers are at play between the one who looks and the subject of that look, who may or may not be aware that they’ve been pierced by a glance? The social, political, and cultural dynamics that govern seeing and being seen are the backbone of queer and feminist media studies. As a media theorist myself, discourses over voyeurism, spectatorship, and (un)reciprocated gazes make up a bulk of what I’ve studied throughout my academic career. Looking is how we perceive and construct images of others, and what goes into that perception is as reliant upon our own subjective interpretation as it is on how others are visually represented.

Much has been made about the sexual politics of men looking at women, but what about men erotically looking at other men? This question brings up the topic of gay cruising, or soliciting casual (and often anonymous) sex through the exchange of glances between men in public spaces. It is a form of quiet communication that expresses sexual availability and interests, a language that poet and University of Oxford research fellow Jack Parlett describes as an eroticized “series of intensified looks, looks which may come and go but nonetheless leave an impression.” His new book The Poetics of Cruising: Queer Visual Art from Whitman to Grindr argues that cruising has “long been a visual culture where image and self-image play a constitutive role” — “an aesthetic phenomenon” articulating the “optical interaction between queer subjects in time and space” in profoundly visual terms. By exploring the historical and artistic significance of cruising throughout poetry, photography, and visual culture, Parlett produces a rich and exciting topography of queer culture that posits a reflexive relationship of vicarious cruising between “cruising texts” and their consumers.

From the very outset, Parlett establishes photographic art as analogous to cruising practices; both are essentially optical phenomena where “acts of looking are intensified and eroticized” into images that can be physically preserved or tucked away into our memory for future use. The “look” of cruising is photographic in nature and utility, instrumentally an “imaginative act of capture” that preserves moments of “erotic perception” shared between two people.

The nature of cruising functions vis-à-vis the “gay public space” where the act of looking unfolds. Historically speaking, urban spaces facilitated cruising encounters because they “reinterpret[ed] intimacy by enforcing proximity between strangers.” Cruising therefore developed in conjunction with 19th-century urbanization and the subsequent development of the gay community in the 20th century. Still, the connection between cruising, public space, and photographic art was not rooted in the invention of the camera, but originated in poetry and the written word (hence the poetics of cruising).

The first two chapters dissect the homoerotic city poems of Walt Whitman (particularly “To a Stranger” and the Calamus section of Leaves of Grass) as both metaphorically photographic and proto-cinematic distillations of cruising. Acts of looking and the optics of perception are intimately lined with the visual throughout Whitman’s work, their perspective frequently assuming “the gaze of a speaker looking upon an exterior world” in an “indexical” fashion in order to “freeze” the moment in memory’s time. This is reflected in the poet’s burgeoning interest in early photography as well as his signature lyrical lists, which silent film director Sergei Eisenstein once described as a “huge montage conception.” Parlett suggests that Whitman’s poetic montage — the “dream-like succession” of “long lists of things” and expansive “tableaux(s) of [the] body” — anticipates the Soviet film montage Eisenstein pioneered in early cinema. More importantly, Whitman’s proto-cinematic approach to the subjects of his poetry emphasizes erotic desire as stemming from “the temporal distance between apprehension and recollection”; “the stranger enters, at the moment of passing, into the erotic archive [i.e. the “spank bank”] of the observer’s mind” as raw material for “erotic creation” that can be reconstructed according to our own desires.

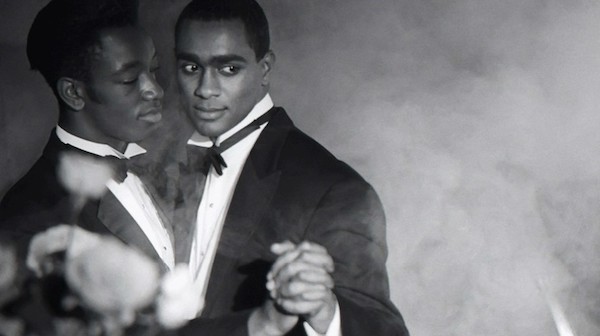

To Parlett, the pictorial component of cruising articulated by Whitman helped establish a particular “semiotic practice” unique to the queer literary and artistic canon. He subsequently turns his attention to the work of Langston Hughes and Isaac Julien’s 1989 short film Looking for Langston to investigate how the “racial and interracial dimensions of desire play out” in cruising texts. Like Whitman, Hughes’s sexuality has been a topic of debate among queer and literary scholars for decades. Whether or not both poets would identify as gay in a modern context is a transhistorical question largely left by the wayside. What’s more important to Parlett is that Hughes’s poetry shares Whitman’s fascination with looking — finding and seeking “unresolved and unspoken threads of queer desire” — in ways strikingly similar to photography and montage. But for Hughes, notions of looking and being looked at are deeply racialized. Citing James Baldwin, Parlett notes that black men’s hypervisibility and fetishization as “‘a kind of walking phallic symbol’” uniquely subjects them to the “suspicious and fetishistic gaze of white men, both straight and gay.” Within the context of the devastating AIDS epidemic, Parlett analyzes the racialized gaze’s function in Looking for Langston and how the film suggests “looking” as a “contested site, where the various intersections of race, performance, and desire are made visible.”

A scene from Looking for Langston.

Though Parlett doesn’t engage much with film theory beyond deconstructing Looking for Langston and detailing the cinematic referents in Frank O’Hara’s and David Wojnarowicz’s artistic oeuvre, his overall analysis lends itself incredibly well to queer filmmaking. In reference to O’Hara’s love of cinema, the idea that cruising engages an “aesthetic economy” that renders potential hook-ups “in relation to photographic or cinematic likeness and to the erotic fantasies attached to movie culture” is heavily reflected in queer visual culture. Case in point: visual allusions to Marlon Brando’s personification of a “rough and rebellious masculinity” in the 1953 motorcycle drama The Wild One are queered throughout Kenneth Anger’s filmography (Scorpio Rising especially) and heavily eroticized in Tom of Finland’s artwork. As often happens whenever I read theoretical analyses, I started to interpret certain films through a similar lens of meaning. Around the time I was reading The Poetics of Cruising, I watched a lot of New Queer cinema from directors like Derek Jarman and Todd Haynes. Looking and the exchange of glances between two people holds a powerful significance in queer cinema, functioning as a motif for unspoken and marginalized desire between men — and women, as evident in Haynes’s Carol — as well as a means of articulating a particular self-image or persona that invokes certain sexual fantasies, as in Haynes’s Velvet Goldmine.

Parlett concludes the book by interrogating how cruising practices have moved from the physical, public space and into the digital sphere with gay hook-up apps like Grindr. The digitization of cruising further reinforces the “visually mediated” interplay of desire by reducing people to a “grid” of images that flattens “‘the reality of another’s body’” into a consumable marketplace commodity. Furthermore, online cruising makes the prejudices of certain gazes all the more explicit: “no fats, no femmes, no blacks/asians/trans/etc.” Although the sort of gay cruising spaces like bath houses and city piers ravaged by the AIDS epidemic are long gone, digital media nonetheless opens up new spaces and possibilities for “the optical and visual dimensions of desire” to evolve. Ending on this note, The Poetics of Cruising leaves readers with a lot to think about. The history of cruising is so much more than colored handkerchiefs and antiquated notions of queer promiscuity; it’s a place where the intersections of race, class, and sexuality overlap in acutely visual ways.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the new podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and Twitter @kuntsuragi for weird and niche movie recommendations.

Tagged: Derek Jarman, Jack Parlett, Nicole Veneto, The Poetics of Cruising, Todd Haynes, crusing, queer visual culture, sex