Author Interview: Jan Brogan on a Revelatory Murder in Boston’s Combat Zone

By Blake Maddux

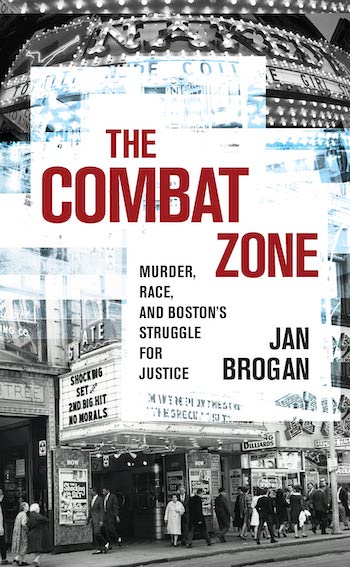

The Combat Zone is more than simply a captivating exposition of legal proceedings and adjacent matters. It is an incisive, vivid, jarring, and meticulous account of — as the subtitle says — “murder, race, and Boston’s struggle for justice.”

The Combat Zone was the area of downtown Boston that had been officially designated in late 1974 to serve as the city’s adult entertainment district.

The Combat Zone was the area of downtown Boston that had been officially designated in late 1974 to serve as the city’s adult entertainment district.

The plan was for it to restrict the proliferation of venues that peddled such wares as live nude entertainment and pornographic material.

Alas, and perhaps — in retrospect — obviously, it turned out to be ground zero for drug-dealing, pickpocketing, prostitution, and mob activity that proceeded more-or-less unabated, due, in part, to on-the-take police officers. The Wall Street Journal characterized it as “a sexual Disneyland.”

On November 15, 1976, Harvard football player Andrew “Andy” Puopolo and his teammates honored the annual tradition of bidding adieu to the season with drinks at one of the area’s many strip clubs.

A few hours after midnight, and altercation broke out among several football players, two prostitutes, and Combat Zone denizens Leon Easterling, Richie Allen, and Eddie Soares.

It ended with Puopolo being assaulted by the knife-wielding Easterling. He and his companions were soon arrested and charged with assault with intent to commit murder.

The trial of the three Black men brought the criminal elements of the Combat Zone and the racist reputation of Boston into sharp relief. Two years to the month after the sentences were handed down, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled that the striking of Black citizens from the jury pool rendered trials unfair for Black defendants. Therefore, a second trial of Easterling, Allen, and Soares was ordered in 1979. That jury reached significantly different conclusions.

In her new book The Combat Zone, author Jan Brogan handles the knotty details of this saga — including its unexpectedly far-reaching consequences — with the expertise and acuity of a veteran journalist and author of four mystery novels.

Her first nonfiction book is more than simply a captivating exposition of the legal proceedings and adjacent matters. It is an incisive, vivid, jarring, and meticulous account of — as the subtitle says — “murder, race, and Boston’s struggle for justice.”

At the heart of her telling is Danny Puopolo, Andy’s grieving, understandably angry, and wholly devoted younger brother.

Jan Brogan will discuss her book The Combat Zone: Murder, Race, and Boston’s Struggle for Justice at the Massachusetts Historical Society on February 23. Click here for details and to register to attend either in person or online.

Brogan spoke by phone to the Arts Fuse in advance of her talk at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The Arts Fuse: Is the murder of Andy Puopolo and the subsequent trials remembered by many if not most Bostonians who were adults at the time?

Jan Brogan: A lot of people remember it. They don’t remember every detail correctly, as it was 45 years ago. Even the people involved don’t. It’s just the nature of memory.

Danny told me that his daughter moved to California and people would say, “Oh, you related to that Harvard football player who got murdered?” It was a really big deal at the time. Part of it was Harvard, that he was a Harvard football player and a young college kid who had his whole life ahead of him and all the advantages going forward.

AF: Who were some of the people you interviewed for the book?

JB: I was able to interview a lot of the people who were there that night, which was really helpful. And I was able to interview all the attorneys, except for [prosecutor] Tom Mundy, who had passed away. But I was able to interview a lot of people who worked with him in the office, and the assistants who helped him in the second trial.

I would have loved to have interviewed a juror in either trial. I sent out letters, but a lot of them were old to start [at the time of the first trial], so a lot of them had passed away. And the first jury was very insistent on not commenting and being anonymous. For the second jury, the transcripts are incomplete, so the jury list isn’t there. There were only like two or three names I could glean from, I think, a Herald article. I wrote all of them and I didn’t hear back from any of them. That was my biggest disappointment. This is why you shouldn’t do a crime that’s 45 years old!

But I was able to spend a lot of time with the Puopolos, which was important. And I was really able to get a lot of time from the lawyers and the Harvard football players who were there, and people who knew Andy and who knew Leon Easterling and Richie Allen. I would have loved to have spoken to more people, but it took me almost 10 years to do this as it was. I feel good about the level of research that I was able to do.

AF: How did the first trial lead to significant reform in how juries were selected in Massachusetts?

JB: I didn’t find out about that until six to eight months into my research. No one knows about that. They interviewed me for Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, and the lawyer interviewing me said that he couldn’t believe that the prosecutor would strike that many Blacks [from the jury] and that he could never do that today. And I told him that you could never do that today because of this case!

When the Supreme Judicial Court said that you couldn’t strike more than a certain percentage of available Black jurors, and California had a similar decision less than a year before, they were considered kind of radical and reformist. Other states did not jump on the bandwagon. It took eight years for the federal court to do that, and their solution wasn’t as good.

Author Jan Brogan. Photo: Amazon

AF: Irrespective of the wisdom of the jury’s decisions in the second trial, were the changes in jury selection that came about between 1976 and 1979 positive ones that were overdue?

JB: Yes. The high court was a good decision on a tough case.

They had to put a stop to the way Blacks were being struck from juries. I don’t think Andy Puopolo necessarily got the justice that he deserved. But at the same time, the criminal justice system was improved, and it was necessary. It was overdue, but Massachusetts was one of the first states to change it.

AF: Boston’s reputation as a racist city figures prominently in the book. Was 1976 the beginning of this or did the year’s events — e.g., the Puopolo murder trials, busing, and “The Soiling of Old Glory” — solidify or amplify something that was already in place?

JB: It had been percolating. But to be fair, New York City or north Jersey, where I’m from, I’m sure Chicago — any urban center that was poor had ethnic tribalism and racism. Boston, I’d say, may have been worse because of its geography.

The racism in the schools and the running of the schools was horrific. The distribution of resources and the unevenness between the schools, that had to change. But the busing and the way they went about it just made matters worse. It made the tension worse and the reputation worse. And when you have this terrible reputation for racism, middle-class Blacks from other areas won’t want to move here.

In short, Boston was already racist and busing made it worse.

AF: Danny Puopolo is a major figure in this book. How generous was he with his time and information?

JB: Danny did not want to tell his own story. He wanted to tell Andy’s story. He wanted to memorialize his brother, who he felt had sacrificed himself for a friend and did not get justice.

He doesn’t like to talk about himself. But he realized that Andy couldn’t be the protagonist. Frankly, it was Danny’s story that really inspired me. I was really fascinated with the trauma that this kind of murder inflicts on the family members. I was really impressed by Danny’s struggles and those of the family. The parents are still alive. They’re in their 90s. I was very impressed with his devotion to his brother’s memory.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins—Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson—in Salem, MA.