Book Review: “Chasing Me to My Grave” — An Indispensable Black Voice

By Patrick Conway

This was an artist who approached his singular craft with equal measures of exuberance and precision.

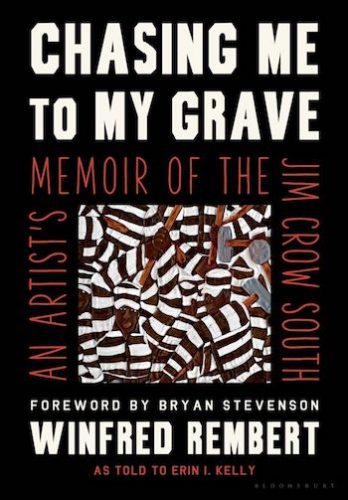

Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South by Winfred Rembert as told to Erin I. Kelly. Bloomsbury, 304 pages, $30.

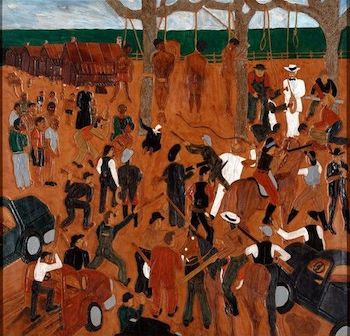

Powerfully amplified by his plain and straightforward delivery, Black artist Winfred Rembert evokes some of the ugliest and most brutal aspects of American history in his posthumously released memoir: “There’s a picture I painted called ‘Almost Me’. It’s a picture of a guy. Dead. Fully lynched. He didn’t survive. He’s hanging there all alone. He can only speak from his grave, and there ain’t much talking you can do from the grave.” In a literal sense, of course, Rembert’s remark about speaking from beyond the grave is accurate. The Black artist passed away in March of this past year, and Chasing Me to My Grave offers most of us a chance to listen to his voice for the first time. His artwork and storytelling are unified by their vivid depiction of scenes from his youth: time spent in juke joints and pool halls, on chain gangs and in Georgia cotton fields, at protests as well as his own narrow escape from a lynching.

The book was written in collaboration with Erin I. Kelly, a philosophy professor at Tufts University, and includes a foreword penned by civil rights activist, lawyer, and Just Mercy author Bryan Stevenson. With both candor and clarity, Rembert recalls different stages of his life. He discusses his childhood, his experiences of political violence, his forays into drug dealing, and his own artistic development, all delivered against the dramatic backdrop of our country’s history of racial cruelty and oppression. Rembert’s paintings are interspersed throughout the volume: they are colorful, complex, and often even revelatory of experiences that are important to unearth and examine. Perhaps most touching are Rembert’s descriptions of his relationship with his wife, Patsy. He describes his marriage as being life affirming, his wife offering him the support (and occasional kick in the pants) necessary to find the courage to revisit and confront a past that is both painful and traumatic.

One of the more notable stylistic aspects of the memoir is it’s plainspoken delivery. At times, its conversational tone can be confrontational, as when Rembert discusses his disdain for wealthy whites in his hometown of Cuthbert, Georgia. They seemed all too eager to celebrate his success once he achieved a certain level of artistic renown. At other points, the writing turns introspective, the artist reflecting on his family and personal relationships, as well as his own behavior and the lasting impacts of violence. Despite the book’s many weighty topics, Rembert does not attempt to moralize or dwell too long on any single trail. He avoids becoming too sentimental; instead, his voice typifies the type of down-to-earth, matter-of-fact resilience that he was forced to develop in order to survive the Jim Crow South and eventually find success as an artist.

Winfred Rembert, “The Lynching, After the Lynching, The Burial.” Photo: Yale Art Gallery.

Given Rembert’s extraordinary personal experiences, it is is a wonder that his art is not overshadowed. The paintings included are a testament to his talent. Rembert talks about his artistic process with zest, detailing how his life experiences informed his art. He also provides an intimate knowledge of his craft. His paintings are distinctive because they were often painted on carved and tooled leather. He takes the reader through the process of soaking the leather, drying it, cutting and beveling it, and eventually the application of dye His joy in the process is evident: this was an artist who approached his singular craft with equal measures of exuberance and precision.

Chasing Me to My Grave will most likely appeal to a number of different audiences. For those interested in American history, particularly in the impact generated by racial oppression, the book stands as a raw and very personal account of the degradations of the Jim Crow South. For fans of Rembert, the memoir offers invaluable insights into both his life story and fascinating artistic process. And for those not yet familiar with Rembert’s work, the volume serves as a compelling introduction to a unique artist who has an indispensable tale to tell.

Patrick Conway is a former criminal defense investigator at public defender offices in Washington, DC and Boston, and a current doctoral candidate at Boston College researching the expansion of higher education opportunities in prison. His writing has appeared in Post Road, Gravel Magazine, and the Harvard Educational Review, as well as received recognition from the Best American Essays anthology. His work and research were recently featured on the Have You Heard podcast. He can be reached on Twitter @PFConway30.