Film Commentary: Time to Reduce Filmmaking’s Carbon Footprint

By Steve Provizer

It is about time that the filmmaking industry is forced to seriously grapple with issues of sustainability.

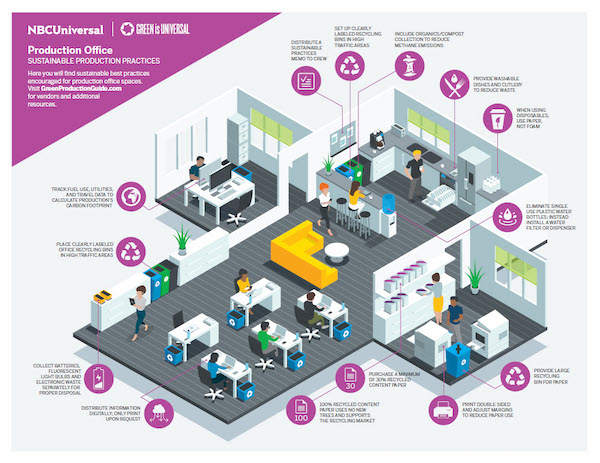

NBC Universal created visual guides to illustrate sustainable production best practices in various settings Photo: NBC Universal.

Over the last few years, the film-television industry has been wrestling publicly with issues of racial and gender representation as well as predatory sexual behavior. It’s responded by adopting new ways to pick the Academy Awards, upping representation of women and minorities in front of and behind the camera, and by holding those who commit sexual crimes to account. But there’s another issue that the industry has yet to be “outed” on. It is about time that it is forced to seriously grapple with its carbon footprint.

Before the pandemic, filmmaking in the U.S. was projected to be a $50 billion industry in 2020. For about a year, the industry barely operated, but an agreement reached between the Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA) and the studios put strict anti-COVID-19 protocols in place. In the last few months, activity has skyrocketed. In Massachusetts, for example, 4 large productions were recently completed and there are 7 others underway.

The last complete report from the Massachusetts Dept. of Revenue (in 2015) says the film industry spent $272.5 million in this state. I’m an actor, a member of SAG-AFTRA , and I know that number has risen considerably in the last few years. Several television series have since found a home here, as well as an increasing number of individual film and television productions. Now that the tax subsidies have been put on a firm footing, this activity will continue to rise. While I’m happy to have the work, I’ve become increasingly frustrated about all of the waste generated on film sets, detritus that is thrown into garbage cans, dumpsters and, eventually, dumps and landfills. On the last three North Shore shoots I’ve worked on, there was not a single recycling bin on the set.

Recycling issues abound: meals served on non-recyclable utensils and plates; uneaten food on dishes tossed away; the waste stream generated by props, costuming, and makeup. Toxic materials, including what’s used for sets, often end up in dumpsters and landfills. The increasing call for computer-generated effects for blockbuster films raises power needs exponentially. There’s also the environmental impact of filming in wilderness or natural surroundings: wildlife and habitats may be disturbed because of sound and light pollution. Vegetation is trampled. You can’t help but wonder: what happened to all those autos that went off cliffs during car chases in thousands of films and TV shows over the past century?

Google “green film sets” and you get the impression that much is being done regarding the enormous amount of waste generated by the filmmaking process. In reality, change has been sporadic and desultory. New York State has created a Seal of Approval to distinguish “sustainable” films. Hollywood’s only widely accepted sustainability project, created by the Environmental Media Association, is the Green Seal program. It recognizes production companies that meet certain criteria but has no way to certify that films have met their standards. The Producers Guild of America has partnered with seven studios to release what they’ve dubbed a Green Production Guide , a toolkit offering free resources to film and television professionals searching for ways to lower their environmental impact. Variety reports that Sony will install solar power panels on each of its soundstages; this will supply 1.6 million megawatts of power, offsetting 8% of the studio’s electricity use. And private companies are around that can be hired as consultants on individual film projects. The industry touts these efforts, but almost no films achieve carbon-neutral status. In fact, the number is embarrassingly low: in the hundredths of a percent.

In this enormous industry, data is hard to come by. There’s no industry-wide method dedicated to accounting for waste/recycling/carbon use. It’s impossible to evaluate what proportion of waste is being dealt with and what is just being dumped. Carolyn Buchanan’s 2016 study notes: “When attempting to determine a movie production’s carbon footprint, it may either not be publically available or it may not be computed internally at the movie studios. Further, production plans, which outline individual budget line items for the production, are extremely confidential.”

The Producers Guild of America Green Report cited above amassed enough data to prove just how useful hard information can be. Their study showed that a particular studio spends an average $11,175 on plastic water bottles during a 60-day shoot. If a case of Poland Spring water costs $8.49, then you’d have to buy about 1,370 cases to make a rounded total of $11,175. 24 x 1,370 is 31,900. That’s 31,900 water bottles in 60 days. Universal Studios, for example, made 17 films in 2018; assuming a 60-day shooting schedule, that would be about 537,031 plastic water bottles a year. From Universal productions alone! And that’s not looking at the waste generated by props, costuming, and set construction.

The Producers Guild of America Green Report cited above amassed enough data to prove just how useful hard information can be. Their study showed that a particular studio spends an average $11,175 on plastic water bottles during a 60-day shoot. If a case of Poland Spring water costs $8.49, then you’d have to buy about 1,370 cases to make a rounded total of $11,175. 24 x 1,370 is 31,900. That’s 31,900 water bottles in 60 days. Universal Studios, for example, made 17 films in 2018; assuming a 60-day shooting schedule, that would be about 537,031 plastic water bottles a year. From Universal productions alone! And that’s not looking at the waste generated by props, costuming, and set construction.

A study from Greenshoot, a UK-based organization, concluded that the average person (in Britain) generates about 7 tons of carbon a year, while a single film technician typically generates 32 tons per year. No such statistics are available for the U.S.

Transportation is also an area of concern. The Buchanan study suggests that flying in talent, crew. and materials from California for Massachusetts shoots results in the generation of a tremendous amount of carbon-burned emissions. The study notes the large number of trips called on to transport talent, crew, and executives from the West to the East Coast — a mix of commercial flights and much more wasteful private airplane trips. And ground transportation usually means a fleet of vans to shuttle crew and actors between “base camp,” set, and catering — which are often miles apart.

Another area of high impact energy use is lighting. LED lights would greatly reduce that waste. How much LED-use will the current technical exigencies of filmmaking allow? Hard to say, but Sony has shot entire features using just LED bulbs. How widespread are their use? The fruits of my anecdotal research: a large Boston-area film rental outfit told me that about half of the lights they rent are energy conserving LED’s.

Last year, I became increasingly fed up with the waste I saw on sets and started to engage in conversations with catering and craft services about the lack of recycling bins or large containers of water. Their response took the form of evasions and shoulder shrugs.

I began to dig deeper, wondering how things might be changed for the better. Although filmmakers first proclaimed their interest in making the industry more sustainable in the early 2000’s, I discovered that undertaking this would mean starting from scratch.

As a member of SAG, I thought the first thing to do was to contact the local union office. The union takes no active part in eco-activities, but it was generally supportive. They suggested I gather together a group of decision makers to discuss the issues; it would include representatives from catering services, craft services, location services, producers, and interested SAG members. Of course, all the would-be attendees would be working. Productions are fluid, people move from production to production, sometimes into different jobs. The chances of finding interested parties who happen to be between jobs and would be willing to participate in such a confab were slim. To get them in the same room at the same time, a near impossibility.

The Center for EcoTechnology in Florence, MA. Photo:Center for EcoTechnology

Sensing a dead end, I looked for an alternative approach and found the Center for EcoTechnology (CET), a non-profit supported by the Commonwealth of Mass to help businesses and other institutions figure out how to deal with their waste streams. I exchanged a number of emails with them, explaining the complicated nature of a movie set. They were willing to help, but admitted that this situation was far different from what they usually did, which is to determine the flow of materials in a building or institution. Clearly, CET would need to spend time observing a variety of film sets. But, when I asked SAG about permission to bring a representative of CET onto a set, they responded that the authorization would have to come from someone in production. But who? They were not really sure who to apply to. Maybe locations? Maybe catering? Maybe the producer?

Stymied, I asked myself: do I have to invent an eco-conscious wheel, or has it already been built? In fact, it has. But it turns out that accessing the expertise of the relevant organizations is difficult.

There are no groups in New England dedicated to dealing with the carbon footprint of filmmakers,, but there is one in New York City called Earth Angel Sustainable Production Services. They describe themselves this way: “Earth Angel is the leading sustainability consultancy servicing film and television production in the United States, providing the STRATEGY, STAFF, STUFF and STATS to easily and affordably reduce the environmental impact of entertainment production.”

I was willing to spend the necessary time in New York to be trained in this black art. My thought is that I would be able to come back and present myself to producers as a qualified eco-supervisor. (There are several names for this service, including: environmental steward, eco-manager, greens-supervisor, greens-person, and sustainability leader.) I hoped I would also be able to train other local people to fill this valuable role. Earth Angel were initially responsive. They said they were working on an “immersion program” and would let me know about its progress. I was advised to subscribe to their newsletter, which would have details of said program, which I did. Unfortunately, I have only received a few newsletters and the program they mentioned has (apparently) never gotten off the ground. I have been in touch with them several times and then applied to be in a 2-week program, but I never heard back.

I also reached out to the West Coast version of Earth Angel called Environmental Media Association, in L.A. They responded quickly and supplied some useful information. But it was unreasonable to think I would get any serious logistical support to foster this work on the East Coast.

What makes this task so hard to accomplish? Filmmaking is organized as a hierarchy, from the director and producer down to the production assistants. Each job is clearly defined — gaffer, best boy, second assistant director, etc. — and each of these people has plenty of hard work to do. Expanding anyone’s job description is most likely a non-starter. Script changes, as well as the amount of footage shot in a given day, may call for shifts in the shooting schedule that require last minute location changes and the readjustment of transportation plans. Special effects snafus happen — something may have to be blown up more than once.

Such problems are not easily overcome and while some aspects of a production obviously need be kept secret, accountability must become second nature in other areas: statistics on travel kept with a requirement to buy carbon credits to offset carbon use; a person responsible for sustainability should be part of the planning and execution team; recycling requirements must be tied to the number of employees on a set; liaison requirements should negotiated with local food distribution and lumber recycling services. Good Samaritan Acts should be passed in states to eliminate liability if you donate food with good intention to a non-profit, so there’s no excuse to not contact local food banks with surplus food.

Producer’s Guild of America.

Filmmaking schools will have to change their habits as well. I have acted in films for students at Emerson and Boston University and can testify that these film schools pay scant attention to the issue of waste on sets. That must be reversed. A commitment to sustainability isn’t just about being altruistic. Recycled set and costume materials can be reused on other films and/or sold to other producers. Using LED lights mean lower electrical bills. Buying water in bulk is cheaper than buying cases of bottles. Purchases of airplane tickets can be reduced by using 3-D imaging teleconferencing technology, which will reduce the number of people needing to be present on location. Massachusetts has grown a large talent base; the industry should increase the number of local hires of cast and crew. Sustainability was not a part of the MA tax-incentive program — and it should be.

The industry has been well aware of this issue for about 20 years and the Green Production Guide provides a good template. But let’s face reality. The call for “voluntary compliance” will simply not be enough. As with any industry that generates enormous amounts of waste, there has to be strong oversight.

The reckoning regarding the racist and sexist side of filmmaking (ageism is still not on the radar) was spurred by outside pressure on the industry. It’s time for activists to demand that movies and their makers do more than issue dire warnings onscreen about the existential threat of global warming. The industry must practice what it preaches and produce its product with net zero carbon output. Actors with clout, ticket buyers, and streaming subscribers must apply pressure on filmmakers so that the industry becomes a part of the solution, not the problem.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.