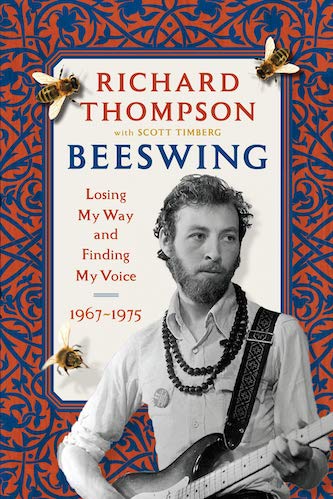

Music Interview: Guitarist and Singer-Songwriter Richard Thompson on His Memoir, “Beeswing”

By Blake Maddux

“I really thought that I could sustain a life in music, but perhaps I’d end up in Las Vegas backing Tom Jones or something.”

In a 2019 interview (which I conducted), guitarist and singer-songwriter Richard Thompson explained why the memoir that he was writing would cover the years 1967-1975 only.

In a 2019 interview (which I conducted), guitarist and singer-songwriter Richard Thompson explained why the memoir that he was writing would cover the years 1967-1975 only.

“One of the problems I have with a lot of music biographies is that they do tend to taper off after about the age of 27,” the Queen Elizabeth II–dubbed Officer of the Order of the British Empire opined. “Your life becomes a lot less interesting in most cases. So I’m trying to hit the interesting years and forget about the other stuff.”

The then in-progress book was published on April 6 and is titled Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice, 1967-1975 (Algonquin/Workman). It covers Thompson’s postwar upbringing in North London, the four years he spent with the pioneering British folk-rock band Fairport Convention, the first three albums that he recorded with his former wife, Linda, and the couple’s embrace of Sufism. (Arts Fuse review of Beeswing.)

From his time with Fairport Convention in the late ’60s through a star-studded 70th birthday festivity at London’s Royal Albert Hall in September 2019, Thompson’s work has been a cause for celebration. The consistently high quality of his output has earned him a 1997 Ivor Novello Award for songwriting, the #19 ranking on Rolling Stone‘s 2003 100 Greatest Guitarists list, the aforementioned OBE title in 2011, and Grammy nominations in 1991, 1996, 2010. The L.A. Times described Thompson most succinctly when it called him “The finest rock songwriter after Dylan and the best electric guitarist since Hendrix.”

Clearly, Thompson — who turned 72 three days before Beeswing was published — has had quite an interesting life since age 27. However, focusing on the specific nine-year span that he does affords space for more detailed recollections as well as brief mentions of, for example, being in a sitar class with Andy Summers, his relation to Syd Barrett, receiving mail from Paul McCartney, noticing that Graham Nash used a bit of his band’s stage banter as a song title, and witnessing John Bonham wallop the drum set of Fairport Convention’s Dave Mattacks (who has lived in Marblehead, MA, since 2000).

The recent New Jersey transplant spoke with me about his first book by phone two days after doing so with Elvis Costello via Crowdcast.

Some serious posing, all in different keys. Malcolm Fuller, Perri and Richard Thompson. © Richard Thompson.

The Arts Fuse: The book is dedicated to your collaborator Scott Timberg, who committed suicide in December 2019. How did you connect with him and how does he deserve to be remembered?

Richard Thompson: Scott was a wonderful writer about music. He worked at the L.A. Times for many years, he was at the L.A. Review of Books, and he was an author as well. I sort of knew Scott socially and we’d done interviews together. My book wouldn’t have happened without him because he was bugging me, saying, “You must write this book about this time period. This is important, this is good stuff.” Finally, he convinced me to get started. He was going to have more of an editorial role at the end of the process, but unfortunately he passed away before that could happen. But he should be remembered as a fine journalist. In Los Angeles, he really had a good reputation.

AF: Why did you title a book about the late ’60s and early ’70s after a song that was released in 1991?

RT: Well, the song is kind of a reflection on the ’60s and people I knew in the ’60s. And, you know, some of the attitudes of that time. A generation of people rejecting the road well-traveled, not necessarily following in their father’s footsteps or going to university and getting straight jobs. A lot of guys I knew at school became drug dealers or hippies, they lived in communes, they went off around the world. They did a lot of alternative things rather than settling down and getting a job. The song “Beeswing” is kind of reflecting people who dropped out of society for some reason or another. Partly voluntarily, in some cases involuntarily.

AF: There is a quote attributed to several different people that goes, “I don’t enjoy writing but I enjoy having written.” Which side of that quote would you say you were on?

RT: Actually, I enjoyed most of the process. I enjoyed writing, but I wasn’t an avid rewriter. When you write a book, you have editors who shove you and cajole you. But I enjoyed it very much. Having written it, I thought, “Should I start over?,” because I could conceive of it in different ways. I could conceive of it as more of a hallucinatory view of the ’60s. The ’60s to me seemed very jumbled, you know, drug- and drink-influenced. But that would have been almost impossible to read. It would have been like reading Ulysses or something.

AF: Did you ever reach out to anyone mentioned in the book to confirm any information?

RT: Not too much. A couple of times I reached out to an old Fairport colleague or something, but they were fairly useless. Everybody, myself included, seems to have a very selective memory of the past. Often their version of history would contradict mine. And I thought, “Well I know I’m right, so they must be wrong!” I kind of wrote it not thinking too much about the structure; then I had to go back afterwards and try to place everything in time, which was probably the most difficult thing, really. I had to rely on websites that have Fairport dates going right back to the beginning. It was incomplete, but at least it was somewhere to get started. I truly wished that I’d kept a journal of that time. That would have been absolutely fantastic.

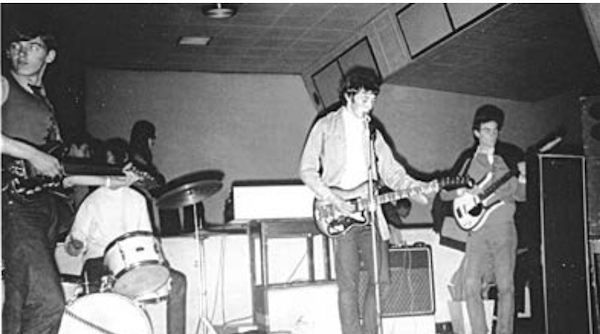

Pre-Fairport with Shawn Frater on drums at the Golders Green bowling alley, 1966. © Richard Thompson.

AF: You write about discovering and learning from your father’s music collection. Do you remember the first recordings that you bought for yourself?

RT: The very first record I ever bought was a terrible record, and I’m embarrassed to tell you. It was called “Friends and Neighbours,” by Billy Cotton. He had a show on BBC radio. When I was young, I thought that this was like the pinnacle of music. It’s like a bad singalong. It’s atrocious. And then the next record I bought was “A Four-Legged Friend” by Roy Rogers. The B-side definitely influenced my musical taste for life. It was called, “There’s a Cloud in My Valley of Sunshine.” I think, basically, I’ve been rewriting that song for the last 50 years! They were 78s, of course. I can see them now.

AF: How well-known was Fairport Convention despite not being chart-topping pop stars?

RT: By the late ’60s we were getting better known. Recently on Facebook somebody reprinted the band’s fees from about 1969. Who was earning what. And Fairport was fairly high up the ladder fee-wise. So we must have been doing quite well. We were as known probably as Fleetwood Mac or something like that at the time.

[“Now Be Thankful” by Fairport Convention, the B-side to which long held the Guinness record for longest song title; and check out that first comment]

AF: You must have been pretty eminent to have received communications from — among others — the Beatles.

RT: The Beatles kind of had their ears to the ground. They were aware of music happening in all different places and were very musically curious. George Harrison came to one of our very early gigs, which I didn’t know at the time, but he commented on it later. The Beatles were very hip to what was going on.

AF: Was Jimi Hendrix a household name when he joined Fairport Convention onstage?

RT: He wasn’t a household name at the time. He was very well-known among musicians. Guitar players were rightly intimidated by him. I was as well, ’cause he could always upstage you if he felt like it! But if Jimi says, “Do you mind if I sit in boys?,” you kind of swallow hard and say, “Well, yes, okay…”

AF: Briefly, how do you justify your claim that “Fairport…really did invent a genre of music”?

RT: In our formative years, we all hung out at folk clubs. We were very aware of traditional music from Britain, but we didn’t think it was a particularly hip or cool thing to be playing. We were far more interested in rock music. But at a certain point, we thought we should put our own culture into the music and start playing something more homegrown. Sandy [Denny] was already singing a lot of traditional songs in her solo shows. Then we really started to rearrange the songs, to turn them into something people really hadn’t tried before. And it became this sort of full-force different strain of rock music that came from Scottish-Irish-English traditional roots. I think that was the difference. We were quite a loud band, and the lyrics were very powerful on those old ballads. That was a great combination. That allowed a movement to happen. And people saw that model from Fairport in other countries — Holland, Spain, Scandinavia — and thought, “Well, we should be doing the same thing. We should be doing this with our culture.”

[“Sloth” by Fairport Convention; again, check out that first comment]

AF: You write on the last page of the book, “At twenty-seven I felt as if I was on the musical scrapheap.” Now those digits are reversed, you’ve just published a book, released an album of new live performances, and will soon (hopefully) be welcomed back to venues worldwide. Would you have bet in 1976 that you would be as active as you are in 2021?

RT: Yes, but I wasn’t quite sure in which context I’d be playing music. I really thought that I’d be a musician for life or for as long as I could keep doing it. I didn’t know if I could sustain myself in a duo with Linda or as a soloist. I really thought that I could sustain a life in music, but perhaps I’d end up in Las Vegas backing Tom Jones or something.

AF: How have you filled the void left by being unable to play live, which you describe as “the best thing…richly rewarding for me”?

RT: It’s been very difficult. I haven’t really managed to fill it. Doing stuff online is wonderful because you can stay connected to the audience, but it’s also weird and not as satisfying to play to kind of nothing. It’s a bit more like being in a recording studio, where you are kind of playing for yourself. Instead of applause you get comments scrolling down at the side of the page. It feels a bit distant. Personally, I can’t wait to get back out there. I’ve got shows being booked for the summer even, and lots of stuff shoved into next year. So it’s looking up.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins–Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson–in Salem, Massachusetts.

Very interesting interview, Richard’s sense of humour shines through as ever. I’m keen to read the book, I must pop along to Waterstones bookshop early next week.

Many thanks

Mike

Thank you very much for reading and commenting, Mike. As I have told others, the book is much more interesting than the interview!

Want the book..but…mainly I want the album with…Lover Don’t Go.. I THINK that is one of Richard’s..please respond..thanks a bunch! sueatherrin@gmail.com