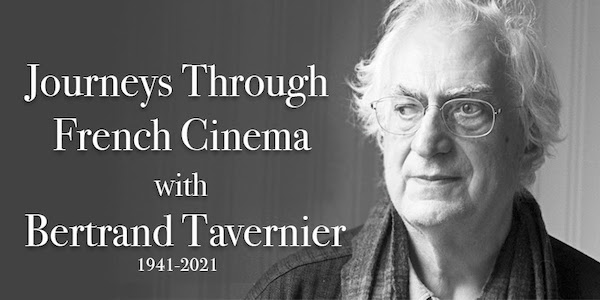

Film Interview: Bertrand Tavernier (1941-2021) Talks About – What Else? – French Cinema

By David D’Arcy

We mourn the loss of an affable, generous man, a bridge to a vast history, who also knew and loved American culture.

The filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier died last week at 79. Two things stuck with you about Tavernier. He was from Lyon, and he was a collegial and inspired authority on everything cinematic.

We mourn the loss of an affable, generous man, a bridge to a vast history, who also knew and loved American culture.

I last interviewed Tavernier five years ago, when he was yet again helping to save great works of French cinema from oblivion via his documentary My Journey through French Cinema, which is available here from Kino. The company is also streaming Travenier’s 8-part TV series Journeys through French Cinema.

This conversation with the writer-director has not been published until now.

Bertrand Tavernier has been a film critic, publicist, screenwriter, director, and producer. And, throughout his life, Tavernier has also been a film historian. We should be extremely grateful.

In My Journey through French Cinema, Tavernier is also an archaeologist, a film lover who has dug back into decades of French film to exhume what’s been neglected, underappreciated, and potentially lost. He would be the first to say that his choices here are personal, but he would stress that his personal attachment to these films and filmmakers makes them no less important. Part of his mission was to salvage what he could from an endangered past. You’ll learn here that some footage was saved before it would have been repurposed into celluloid for making combs. The subtext to Tavernier’s erudite screen travelogue is plain: this is a plea for film preservation.

Some of the names are familiar. He reflects on Jean Renoir, Jean Gabin, and Jean-Luc Godard. (He worked as Godard’s press agent.) We see footage from the films of Jacques Becker, Jean-Pierre Melville, Marcel Carné, and Jean Sacha. They’re worth knowing and remembering. In addition, the documentary is a way to learn about the films that inspired Tavernier to become a filmmaker.

Tavernier, the director of many films (‘Round Midnight, The Princess of Montpensier, A Sunday in the Country, Coup de Torchon, Life and Nothing But, L. 627, Fresh Bait, etc.), does not make a pitch in this documentary for his own varied and underappreciated work. Will Tavernier’s own efforts be relegated to the same back drawer of memory where we find the neglected movies in My Journey through French Cinema? Let’s hope not.

Watching Tavernier’s doc of more than three hours, you’ll feel that there’s still plenty more to say about French movies. No surprise.

The Arts Fuse: Why did you make My Journey through French Cinema?

Bertrand Tavernier: I wanted to look at and show the work of filmmakers who were underrated and unknown, even in France now, but especially in this country, starting with somebody like Jacques Becker. Becker, among the super-great filmmakers, is somebody who is very badly ignored in America. You practically never find essays about him, articles on his work.

But the first intention was to share my admiration, the love that I have for some of those filmmakers or composers, and hoping that it would put them on the map. When I was making the film it turns out that my editor was first hearing about some of these old movies, and he rushed to see them. He was so excited. He discovered at least 100 films which he loved.

I think admiration is contagious, and it’s something which opens your mind. If the film inspires some people to search for those films, to write about those films, to study those directors and composers, I will have succeeded.

AF: Was there enough archival material — and resources — out there for this project to be accomplished as you envisioned it?

Tavernier: I didn’t receive any help, at least not at first, and not from the National Center for Cinema (CNC, Centre National pour le Cinéma). The project was stopped twice. I was forcing the CNC to investigate who had the rights to these films. I was forcing the people who owned the films to discover that they had titles that they knew nothing about.

I succeeded at 80 percent. I had to take out some films which had not been restored, and sometimes we had to work with very bad copies of things that a friend might have given us, so the images were horrible. We were hoping that they might be restored, and very often they were.

For instance, Cet Homme Est Dangereux (Jean Sacha, 1953) is now beautiful to look at. Casque d’Or (Jacques Becker, 1952) is stunningly beautiful. So we succeeded, I think, in helping to restore many films. Gaumont discovered that there were many films that it owned, like Le Garçon Sauvage by Jean Delannoy (1951), which is nearly a masterpiece. So restoring that film already has had a positive effect.

There was a moment when the dramaturgy of the film imposed a particular direction. It was not accepting films from some directors. This was not a value judgment, but because they did not fit into the narrative’s construction. So I decided to do an eight-hour series for TV with everything that I could not put into the film (Journeys through French Cinema).

AF: What’s your intended audience?

Tavernier: I don’t know. It’s like a fiction film. I don’t know — people who are curious, who want to remember some memories. If I had an audience in mind, I would not have made any of my films because, most of the time, as with my fiction films, people told me that there was no audience. They said that there would be no popular interest in ‘Round Midnight (1986). They told me that their expectation of a domestic audience was zero — not a single spectator. The film was financed by video sales and by foreign sales. The film had two Academy Award nominations and it won one for best music. Life and Nothing But (1989) — I was told by the head of the conglomerate, the person above my producer, that I had to abandon the film, because I would not have a single spectator anywhere for such a story. Nobody would come. And he said, “Here is a check, paying your whole contract, so that you won’t make the film. And here’s another check, for an open contract on any subject you want.” And I said no.

The film was a hit, and won about 25 international awards, and was a success in many countries.

It’s the same thing with this documentary. I was told that nobody would come, until Gaumont and Pathé thought it was important, perhaps not for generating audiences, but for France, for the reputation of French cinema, for the knowledge of the French cinema, that it is something that should now be shown in schools, in festivals, in retrospectives, in the cinématheque. I hope so. Jean Renoir said something memorable to me about this that has been quoted a lot: “You have to make a film thinking that you’ll change the course of history — you need that arrogance — but you also must be humble enough to think, if you touch two people, you’ve done something extraordinary.”

Here’s a story. I was approached by a young Black guy, his name, I remember, was Kelly White. And he said, “You know, I love your films, and you know that quotation from Renoir. I’m one of the two people, and your films have changed my life.” That was very moving.

AF: Let’s talk about your focus on music in the film.

Tavernier: Film critics and film historians ignore music. Sometimes they’re right. In some American films, the music seems to be made for listening to in a massage parlor, just pianistic things. In American cinema, when the studios put 85 minutes of music into a 90-minute film, it destroyed the notion of music, even though there were some superb composers — [Erich Wolfgang] Korngold, Miklos Roza, before Bernard Hermann, before Jerry Goldsmith.

But in France it was different. In France, I discovered that many great directors knew a lot about music. René Clair worked many times with the same composer and he gave him directions. For example, in Les Belles de Nuit (1952), you have to play the scale, do re mi fa sol…, just the scale. And Becker asked Paul Misraki in Montparnasse 19 (1958) to use only four notes. Julien Duvivier was a great music lover. In Golgotha (1935) [a drama about the crucifixion of Christ] the first card [in the credits] of the film is “a film by Julien Duvivier,” and on the same card it read, “music by Jacques Ibert.” Ibert was a great classical composer, very important. He was so well known that Orson Welles asked him to write the music for Macbeth, which has been completely forgotten. And Welles also asked Misraki to do the superb score for The Confidential Report of Mr. Arkadin (1955).

Bertrand Tavernier in his office. Photo: Criterion.

Composers are never mentioned in books about the history of the cinema, never mentioned. The fact that they changed the mood of a film or understood what a film was about is rarely studied. The intimacy between Maurice Jaubert and Jean Vigo, between Maurice Jaubert and a lot of directors, made him perhaps the best composer of the ’30s. There’s also the fact that the French directors were among the first, after Carol Reed and The Third Man, to use one instrument — like the guitar in Forbidden Games, like the harmonica in Ne Touchez Pas au Grisbi (1954), or Miles Davis’s trumpet. At the same time, the Americans — because a lot of the composers were Viennese, Hungarian, or German — often used enormous orchestras to perform great scores. Jaubert made use of 12 or 15 musicians for Vigo’s L’Atalante (1947), with instruments that were not used in American films, like the saxophone, like the accordion. It’s only in the ’50s and the ’60s and the ’70s when you have American composers who are doing that kind of thing, like Goldsmith in Chinatown (1974), where I think there were five or six instruments. And you have the trumpet player playing the high notes in The Band Wagon (Vincente Minnelli, 1953).

AF: About Jean Renoir, whom you cite as writing letters condemning Jewish influence in French cinema and seeking to promote the collaborationist regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain. In the film, Jean Gabin says “Comme metteur en scene, c’était un génie; comme un homme, c’était une pute.” That translates into “as a director, he was a genius; as a man, he was a whore.”

Tavernier: Gabin said that to me. The auteuriste position is bad when it is used to excuse everything in the director. So when the director is old, and his film is done in an incompetent way, it’s “the work of an Old Master,” as if we’re talking about painting.

That [same position] is used to excuse some bad films of Howard Hawks — I mean, Rio Lobo is a terrible film. To try to find any kind of quality there is an insult to the masterpieces like Only Angels Have Wings or Red River.

Renoir, you couldn’t touch him, he was perceived to be a saint. It was reported several times that his behavior was at least debatable, some people even said it was shameful. But most turned against the people who made these serious charges. Now these facts turn out to be true. When Renoir’s correspondence was published some of the letters were horrifying.

Jean Gabin in French Cancan.

I think Gabin, who was very patriotic, never forgave him. Gabin enlisted in the army. He fought in the Italian campaign. And to see the man whom he admired the most behaving like that was a shock. So when they met again on a very good film, French Cancan (1955), it was not the same kind of relationship. It was correct, professional, but it was not the love that existed at the time of La Grande Illusion (1938) or La Bête Humaine (1940).

AF: Gabin seems to have played against type behind the scenes — reading scripts carefully, editing them when he felt something wasn’t right. He had his own ideas about how drama worked.

Tavernier: Sometimes, at the end of his life, Gabin was protecting himself, but of all the actors that I’ve met, he was the one who spoke the most beautiful French. It was full of slang, full of images, but it was so inventive, it was so personal. And his vision of the cinema could be very interesting. I remember the first time that I met him, and I said that the credits of La Marie du Port by Marcel Carné (1950) read that the film was written by Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, a Dadaist poet. And Gabin said that it was impossible, because you couldn’t speak any of the lines. He said that the real author was “my friend Jacques Prévert,” and that Prévert rewrote the entire screenplay.

I asked Prévert, “did you do that?” And he said, “yes, I did. At that time, I had a bad relationship with Carné, I wasn’t speaking to him, but I rewrote that.”

[laughing] And I have, framed in my house, a review written by a French critic, saying that this is the first great film by Marcel Carné, because it’s not written by Prévert.

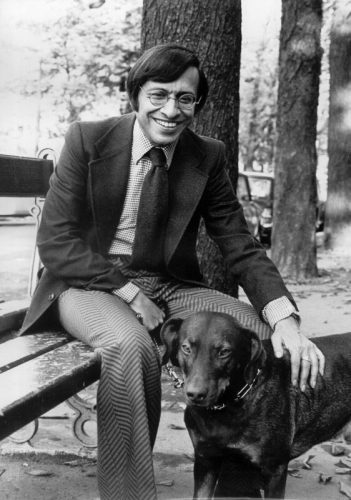

Robert Benayoun — “He had something that very few critics had. He was very educated.”

AF:: In your section about Jean-Luc Godard, you talk about how he didn’t want critics who praised him to come on the set of his film Le Mepris [or Contempt] (1964). He didn’t want to be bored by them. But he did allow Robert Benayoun of [the film journal] Positif to come, even though he had trashed Godard’s previous films.

Tavernier: I was the press agent on the film, and I tried to make Benayoun change his mind, because I thought he was unfair. Godard wanted to speak only to him. He said, “don’t bring a guy who has already written a book about me, he bores me to death with his praise. I want to have an argument with Benayoun.” Godard at the time was very provocative, very funny. I did three films with him, and we stayed in touch over the years. That was a great lesson.

AF: Benayoun has a forgotten film of his own, the marathon documentary on Jerry Lewis, Bonjour Mr. Lewis (1982).

Tavernier: As for Benayoun, he was very unfair regarding Godard and some other New Wave directors at the time, but he was ahead of his time when he praised Jerry Lewis, analyzing his films, as well as writing great books about Buster Keaton, about Harry Langdon, and about slapstick. He had something that very few critics had. He was very educated. He knew poetry, he knew books, he knew novels, he was an expert on paintings. And he wrote extremely well. He hated some directors, but when he was writing about the things he loved, he was marvelous. He wrote about the traditions of comedy in the Yiddish theater. He hadn’t discovered cinema, as many critics today have, with the cinema of Tarantino.

AF: Everything film critics know today seems to come to them by way of cinema. When you mention that Benayoun, who died in 1996, had a great education. That is admirable, but it’s rare.

Tavernier: It is rare, but it wasn’t always so. I quote journalist Michel Cournot on the 1965 masterpiece of Pierre Schoendoerffer, La 317eme Section (Platoon 317). Cournot was a great poet, a great, great poet. And he wrote the best book about shooting a film, the novel Le Premier Spectateur. It’s incredibly funny, only dialogue with a few descriptions. You slowly understand the violence, the pain, the excitation, the difficulties that a film director endures.

It ends with a monologue where the director says to his sound engineer, “I know I’m a pain in the ass, but I have to be like that.”

“At the same time that I’m on the set, solving a problem,” [the director says,] “I am in the cinema, watching my film. It’s a cinema in Poitiers or Angouleme, not well heated, the projection isn’t good, the sound’s not great. As I’m watching a scene, suddenly I discover that the woman sitting next to me isn’t attentive. She doesn’t understand what’s grabbing the main character, because a shot isn’t precise enough. I am on the set, but I’m also the first spectator.”

He’s the first spectator and suddenly, for a brief moment, he feels that he must do what he can so the people sitting next to him will forget their tax problems or the fact that they won’t be paid at the end of the month. He’s giving them something. In Cournot’s book, this is the reason why the director is so horrible, and why he may be even more horrible doing his next film.

AF: What do you find encouraging and discouraging in French cinema today?

Tavernier: There are plenty of exciting films made by exciting directors – Benoit Jacquot, Arnaud Deplechin, Emmanuelle Bercot, I like some of the films of François Ozon. And there’s a great variety of films — some great cartoons, great documentaries. What is discouraging is that sometimes those films take a long time to be financed. All directors have to fight against a dictatorship that says you should make comedies.

Jean Gabin, left, and Arletty star in Le Jour Se Leve. Photo: Productions Sigma.

I have some knowledge of history and I can say that Carné, Duvivier, and Renoir had the same problem. Why make La Grande Illusion, why make Le Jour Se Leve when there’s some great vaudeville that’s making much more money than you are? And they were [making much more money], and they are totally forgotten now, impossible to watch.

Here’s a funny thing. The official selection of the French government for the Venice Film Festival of 1934 was Bouboule I, Roi Negre. I’ve seen the film. It’s a comedy, set in Africa, where all the Black people are cannibals — done as a gag, as a joke. It’s rather depressing now. It was the official selection in 1934 in Venice.

AF: Mussolini must have loved it.

Tavernier: Yes. I wanted to include a scene from it in the series. You have Bouboule, played by a singer at the time who was very popular, George Milton, and he falls into a trap. He ends up there with a hyena. And he says in French, “la, ou il y a de la hyenne, il n’y a pas de plaisir.”

It’s a play on words with the proverb, “la, ou il y a de la gene, il n y a pas de plaisir.” [ translated very loosely as “there’s no need to stand on ceremony”]

I wanted to quote that. People call it “the golden age” of the French cinema. Look what you had.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Bertrand Tavernier, French cinema, French film history, Journeys Through French Cinema

What can make a lover of cinema happier than hearing Bertrand Tavernier talking about movies? Thanks, David, for the lovely interview and the knowledgeable questions.

“Jean Gabin, left, and Arletty star in Le Jour Se Leve. Photo: Productions Sigma.”

Arletty? She looks like the romantic interest in the film, Jacqueline Laurent as Françoise.

Thanks for the inspiring talk. Must see the TV series.