Visual Arts Favorites 2019

Our critics sound off on some of their most striking visual art experiences this year.

Kathleen Stone

“Chamonix,” Joan Mitchell, about 1962. Oil on canvas. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Museum of Fine Arts mounted an ambitious show of art made by women that I ultimately found unsatisfying. Still, the show Women Take the Floor contained many outstanding pieces. If I had to name one that has stayed with me, it would be Joan Mitchell’s Chamonix. The painting manages to depict the iconic mountain in icy tones of white, black, and blue, applied via jagged strokes. At the same time, Mitchell, who painted it in 1962, conveys a vision so immediate and personal that one can practically feel the pressure of her hand on the brush as it pushes against the canvas.

Speaking of artists underappreciated in their time, as Mitchell was, I enjoyed the small show, also at the MFA, of mid-century works collected on a provisional basis. The idea was that the museum would assemble a collection outside of the normal acquisition process and then later decide which pieces to retain and which to deaccession. Most were kept and they’re now on view in Collecting Stories: A Mid-Century Experiment. Collected from all over the country, the works reveal how artists were experimenting with technique and exploring a variety of subjects, even as the media gaze centered on Jackson Pollock and other, mostly male, New York abstract expressionist painters. Thanks to Zoë Samuels at the museum for walking me through the show and to the Henry Luce Foundation for underwriting it.

The Hood Museum at Dartmouth College did many things right in its redesign. One was hiring the architectural firm of Tod Williams Billie Tsien; the museum now feels open and welcoming. Another was to rehang its collection with a focus on pieces that did not receive adequate attention in the past, and to commit to frequent rotations. Today the collection, augmented with pieces on loan, is really compelling. I was particularly excited to see the quantity and variety of contemporary African art.

I took two road trips this past year, and made art a major interest during both. One trip was along the western and southern shores of Lake Erie, with stops in Detroit, Toledo, and Cleveland. All have major museums with outstanding collections, a remnant of their profitable industrial pasts. In Detroit, I saw the splendid Diego Rivera murals, plus the rest of the collection, which includes fine Impressionist works. At the Toledo museum, there was an impressive show that combined 20th-century music and art — a feat of innovative curating. When I arrived in Cleveland, the photography exhibit Gordon Parks: The New Tide, 1940–1950 was near the end of its run. I thought I knew Parks’s work, but I was wrong; it is more diverse, incisive, and beautiful than I had appreciated before. In February 2020 the same exhibition will be shown locally, at the Addison Gallery in Andover. I’ll definitely see it again and recommend it to others.

On my second road trip, I headed south. My first stop was the High Museum in Atlanta, Georgia, where the collection includes significant pieces of contemporary African art. Just as at the Hood, the art was exciting and diverse, a sign of the dynamic aesthetic trends coming from Africa. The High also has a significant collection of folk and self-taught art, much of it Southern and African American, all of it splendid. The next stop was further south, in Montgomery, Alabama, where I visited the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, both projects of the Equal Justice Initiative. The art in both institutions explores various historical narratives — of slavery, segregation, lynching. There is also an examination of a justice system that works unfairly against African Americans. At the Legacy Museum, a particularly outstanding piece is a bronze statue in honor of Michael Brown, part of artist Sanford Biggers’s BAM series. Other work by Biggers, drawn from the same series that honors black victims of police violence, was on view at the Tisch Family Gallery at Tufts University. That should remind all of us to make a resolution for the New Year to visit the many museums that are part of New England’s academic institutions. You can often see work equal to what’s on view at the stand-alone museums.

Mark Favermann

In no particular order:

1. The Peabody Essex Museum’s $125 million expansion and renovation in Salem, MA

PEM added 40,000 square feet to the main PEM facility. It includes 15,000 square feet of Class A galleries, a light-filled atrium, an entry for school and group tours, linkages to existing galleries, and a beautiful 5,000-square-foot garden. Now the ninth-largest museum in America, PEM has taken the new wing as an opportunity to reflect — with honesty — on its complicated history and examples of unsavory acquisitions.

2. A Creative Camelot — The Bauhaus and Harvard University at The Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, MA

An inspiring show that celebrates the 100th anniversary of the founding of The Bauhaus and its relationship to Harvard University.

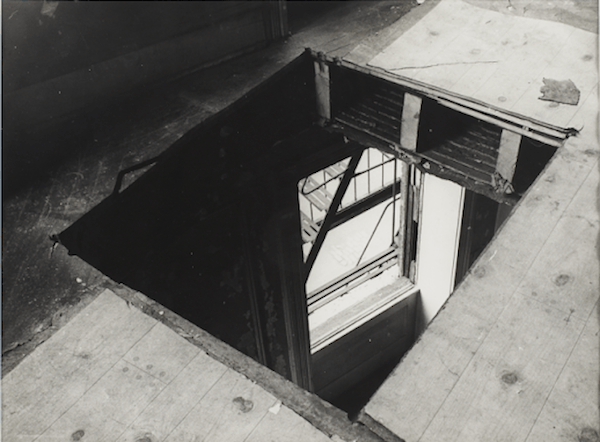

“Infinite Light” by Gordon Matta-Clark, 1972 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner.

3. Gordon Matta-Clark, Anarchitect — Anarchy + Architecture at Brandeis’s Rose Art Museum, Waltham, MA

An exhibit that presents a creative, insightful, and pioneering look at urban blight from the ’60s and ’70s, from an artist who died much too young.

4. Contemporary and Antediluvian — Judy McKie At Gallery NAGA

Functional art by mastercraftsperson and artist Judy McKie that draws on a personal mythology in which animal and plant forms are abstracted yet recognizable, anthropomorphic though strangely primeval.

5. Andy Goldsworthy’s “Watershed” — Mysterious Simplicity

Land artist Goldsworthy’s Watershed is an unadorned but stunning permanent addition to the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA.

6. Patronicity

The city of Lawrence, MA, using matching funds from Mass Development’s Patronicity Program and the Essex County Community Foundation, commissioned artist John Powell to create Iluminación Lawrence, a citywide lighting project that created an immersive public art gallery through the use of LED lighting and projections. The Town of Hull also used Patronicity to bring in several artists to create an ArtWalk made up of temporary walls and sculpture located across from Nantasket Beach.

7. Almost every project sponsored by Now+There: the wonderful Sunflower Seed Project, which distributed 10,000 seeds by artist Ekua Holmes throughout Boston’s Roxbury Neighborhood; artist Nick Cave’s joyful but also a bit creepy Augment, and Pat Falco’s thoughtful MOCK, which examined Boston’s Housing crisis by way of a mock-up of a traditional three-decker located in the booming upscale Seaport District.

8. A favorite visual arts institution of mine (with whom I have worked in the past), Boston Cyberarts, and its series of cutting-edge art and technology exhibits at its Green Street Gallery above the Green Street Orange Line MBTA Station in Jamaica Plain. In addition, there is the organization’s sponsorship of rotating digital artists on the Boston Convention Center’s huge marquee; its Greenway Conservancy Augmented Reality (AR) exhibit, which blends interactive digital elements with real world environments; and its commitment to commissioning artists to create digital experiences at Boston Properties’ new video wall in the courtyard at 100 Federal Street. To Boston Cyberarts, the future is now.

9. The purchase by an anonymous donor of the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed Usonian residence, Kalil House (1957), in Manchester, NH. It was then given to the Currier Museum to go with its stunning Zimmerman House (1951) down the block. Eventually, Kalil House will be open to the public as well.

10. One of the worst public art happenings of 2019 was the choice of The Embrace for the Martin Luther King/Coretta Scott King Memorial on the Boston Common. In this case, crowd-sharing superseded sound choices. What we have is a clunky, awkward, 22-foot-high bronze sculpture of hands embracing (or is that wrestling?). At least this mistake should be a learning experience: drawing on the verdict of the lowest common denominator is no substitute for knowledgeable and aesthetically sensitive decisions regarding permanent public art and architecture.