Theater Review: “The Haunted Life”– The Lyricism of Jack Kerouac’s Formative Years

By Jay Atkinson

It’s Shakespeare in Lowell –the stage piled with ghostly corpses, the heroes all dead, the young bard in mourning.

The Haunted Life by Sean Daniels. Based on the book by Jack Kerouac. Directed by Sean Daniels and christopher oscar peña. Staged by the Merrimack Repertory Theatre (produced in collaboration with Jim Sampas and The Estate of Jack Kerouac) at 50 East Merrimack Street, Lowell, MA, through April 14.

Actors Vichet Chum and Raviv Ullman in the MRT production of “The Haunted Life.” Photo: Meghan Moore.

In the Author’s Introduction to Jack Kerouac’s 1960 novel, Lonesome Traveler, the Lowell, Mass. native states that he “set a record at Columbia College cutting classes in order to stay in dormitory room to write a daily play.” The Merrimack Repertory Theatre’s adaptation of Kerouac’s “lost” novella, The Haunted Life, written in his formative years, reflects the best and the worst of the Beat icon’s early work. In a palpable sense, the MRT’s production is literary kin to those first-born plays Kerouac scribbled in his Columbia dorm as World War II approached.

The strength of MRT artistic director Sean Daniels’ adaptation — his script and direction — include capturing the protagonist Peter Martin’s lyrical optimism, leavened by a keen awareness of his own mortality and that of the people he loves. This is the foundation of Kerouac’s work, running like a dark vein of gold from his juvenilia (produced while a student at New York’s Horace Mann School in 1939) to his later work, including the mournful 1962 novel, Big Sur. Jack Kerouac loved America with the pure heart of an immigrant, the edge of his yay-saying adventurousness blunted by a melancholy romanticism.

With a stripped down cast and bare bones staging, Daniels and his five actors wade through Kerouac’s ocean of words, sometimes effectively and other times, not so.

Peter Martin, soulfully portrayed by dark-haired Raviv Ullman, is a Boston College track star living with his parents in Lowell. Joe Martin (Joel Colodner) is an unapologetic racist who owns a print shop, and Vivienne Martin (Tina Fabrique), a warm-hearted homemaker who dotes on her son, speaking affectionately to him in their native French. Peter is spending an aimless summer in Lowell between semesters, listening to the Red Sox on the radio and to his father’s bitter rants. Young Martin also spends time emoting with his childhood friends, Dick Sheffield and Garabed (both played by Vichet Chum); sparring with his on-again, off-again girlfriend, Eleanor (Caroline Neff); and getting drunk.

As a writer, Kerouac rarely featured set pieces of narrative action, and neither does this play. The five actors almost never leave the stage, which is encrusted with a huge collection of windows, suggesting a crowded urban neighborhood. For example, when Peter and Joe Martin are engaged in a conversation dominated by the paterfamilias, the other actors watch from the sidelines, delivering exposition in the form of soliloquies. At times, these speeches are helpful, but often come across as staged readings of Kerouac’s ornate, multi-layered prose.

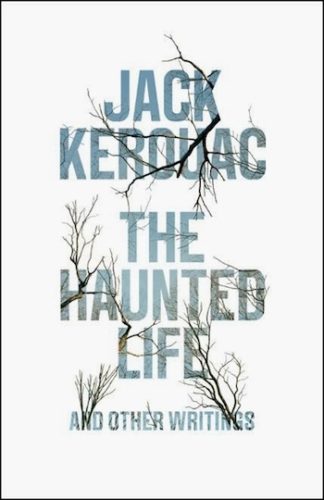

Jack Kerouac in his football playing years.

My companion, a high school English teacher, said that the first act dragged somewhat, as she found it hard to distinguish between the characters. Chum is playing three of them — Garabed, Peter’s boyhood chum and founder of the Young Prometheans; Dick Sheffield, a fellow Lowell High athlete; and Peter’s Merchant Marine shipmate, Bakkedahl. Chum sports a poet’s scarf to signify Garabed, and other times, a dark sweater and cap. But it becomes a tiring exercise to keep these characters straight, especially in the first act.

It’s important to note that Daniels’ script for The Haunted Life is the most recently discovered lens through which Kerouac examined several versions of the same story. Unlike most writers, Kerouac gave up traditional revision methods based on line editing, instead focusing on full draft composition. (A persistent Kerouac myth is that he abandoned revision altogether, but the many partial drafts of his signature novel, On the Road, disprove that notion.) It’s clear that his 205-page novella, The Haunted Life, was a practice session for his 1950 novel, The Town and the City, the tale of young Peter Martin and his family reckoning with their idyllic lives as the second world war looms.

The Town and the City, in turn, was an extended warm up for Kerouac’s later work, especially his novels, Maggie Cassidy and Vanity of Duluoz, where he treads back over his youthful achievements in football, track, and baseball. In fact, Kerouac’s unrealized final project, The Legend of Duluoz, a compendium of his novels with the real names inserted, is an epic re-examination of that same period in his life. This palimpsest runs from 1938, when he emerged as a Lowell High football hero, to approximately 1947, when he turned 25. Kerouac would agree with Flannery O’Connor’s observation that “anybody who has survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days.”

The 279-seat MRT is located in a grand brick edifice on East Merrimack Street in Lowell. Built in 1909, the theatre and adjacent Lowell Auditorium are situated near the old Lowell Sun building, where Kerouac worked briefly as a sportswriter. Gloomy and atmospheric, the theater is crammed with the ghosts of what Kerouac called “O Lowell of my soul.”

During intermission, as I waited for my companion to fetch a drink from the bar, the maze of hallways connecting the theatre with the auditorium was thronged with skinny girls in bespangled dance costumes waiting to go into the auditorium. Coltish, young, and wearing expressive make up, they gabbled in the high-pitched voices of excited performers. Here and there, pairs of teenage dancers waited solemnly in their matching costumes, talking in the whispered shorthand of old hoofers, stretching their calves, practicing heel-toe maneuvers, and knotting their hands. This is the sort of thing Kerouac would have noticed and taken delight in, causing him to miss the opening of the second act.

Don’t miss that curtain. The first act concludes with a radio announcement that the Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor. There’s an earsplitting cannonade of war sounds (created by sound designer David Remedios) and the set is plunged into darkness. That darkness, and the tension it brings to the play’s second act, continues to gather despite the brightly lit stage. Against his parents’ wishes, Peter ships out with the Merchant Marine. Joe Martin loses his print shop, and he and Vivienne must sell their house. Peter’s beloved friend Garabed is killed overseas (his personality and experience modeled on Kerouac’s childhood muse Sebastian Sampas, a U. S. Army medic who was killed at Anzio.) Peter’s little mentioned and never seen brother, Wesley, is also killed off stage, like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Joe Martin is diagnosed with cancer, reconciles with Peter, and dies. It’s Shakespeare in Lowell –the stage piled with ghostly corpses, the heroes all dead, the young bard in mourning.

Although Joel Colander as Joe Martin and Vichet Chum, playing a raft of characters, engage in bombastic speeches and take turns chewing the sparse, bony scenery, the heart of the play is Raviv Ullman’s Peter Martin. As a writer, and a character in his own story, Kerouac had a profound interiority, something that’s opposed to the outwardly charismatic people he traveled with. Ullman’s performance is the eye of the storm — Kerouac’s dark brow, compassion, and wistful loneliness are all present in the character. Even when surrounded by the other actors, Peter seems alone on stage. Ullman’s deft underplaying captures Peter’s brooding nature, budding alcoholism, and the apprehension of his lost youth.

Although Joel Colander as Joe Martin and Vichet Chum, playing a raft of characters, engage in bombastic speeches and take turns chewing the sparse, bony scenery, the heart of the play is Raviv Ullman’s Peter Martin. As a writer, and a character in his own story, Kerouac had a profound interiority, something that’s opposed to the outwardly charismatic people he traveled with. Ullman’s performance is the eye of the storm — Kerouac’s dark brow, compassion, and wistful loneliness are all present in the character. Even when surrounded by the other actors, Peter seems alone on stage. Ullman’s deft underplaying captures Peter’s brooding nature, budding alcoholism, and the apprehension of his lost youth.

In Act 2, Peter and his girlfriend Eleanor grow apart, and in a final attempt at rapprochement, she visits him in New York. It’s February 1942, and a voice on the radio announces that a German U-boat in the Labrador Sea sank Peter’s Merchant Marine ship, the SS Dorchester. Reflecting one of Kerouac’s actual experiences, when he barely missed shipping out a second time with the Dorchester, 650 lives were lost, including several of his friends. Plunged into reverie, Peter says, “I ride the bus and all I see is empty seats…. every seat represents a son, a father, a brother.” That’s all we need here, and Joe Martin’s high-minded soliloquy that precedes it defuses a genuinely theatrical moment.

Despite Kerouac’s adventurous life, abundant source material, and matinee idol looks, it’s never been easy to capture his “book movies”, as he called them, on the stage or movie screen. Beginning with Kerouac’s narration for Robert Frank’s avant-garde film Pull My Daisy (1959), extending through misfires like The Beat Generation (1959) and The Subterraneans (1960), and including Hollywood productions of On the Road (2012), Kill Your Darlings (2013), and Big Sur (2013), Kerouac’s torrent of stories have been nearly impossible to render visually.

Daniels and his troupe have run up against the same difficulties that bedeviled these productions — how to reconcile Peter Martin’s inner turmoil and outer composure in a visual medium. By reworking the play’s first act, trimming speeches, and making the characters separate and distinct through inflection and wardrobe, Daniels could move The Haunted Life to the top of that list.

Jay Atkinson is the author of Paradise Road: Jack Kerouac’s Lost Highway and My Search for America, and seven other narrative books. His eighth book, Massacre on the Merrimack: Hannah Duston’s Captivity and Revenge in Colonial America, won the 2016 Massachusetts Book Award Honors in Nonfiction. He’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize four times, and teaches writing at Boston University. You can e-mail Jay at jaya@bu.edu, or follow him on Facebook or Twitter.

Great review!