Book Review: “No Way Home” — A Memoir with Quirk and Heft

No Way Home is a model for how to tell a weird, complicated story in a way that will make the reader hang on tight for the whole ride.

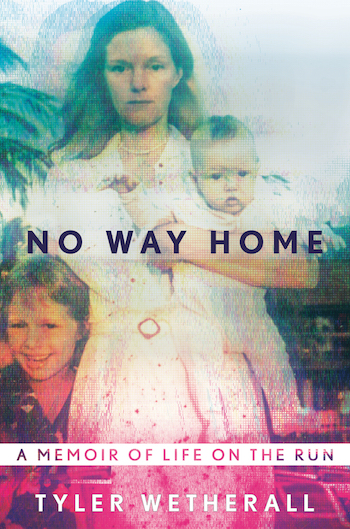

No Way Home: A Memoir of Life on the Run by Tyler Wetherall. St. Martin’s Press, 320 pages, $26.99.

By Katharine Coldiron

No one would ever wish for a traumatic childhood just to have something good to write about. No writer sets out to have a messy life for the sake of penning a searing memoir later. But when life happens that way, and the writer is skilled enough to record his or her life compellingly, an opportunity to publish that story will likely appear. Such is the case with Tyler Wetherall’s first book, No Way Home, a memoir about Wetherall’s life as the daughter of Ben Glaser, a major marijuana smuggler. In the mid-1980s, Wetherall’s family “went on the run,” moving through a dozen houses in Europe in just a few years. Ultimately, after her parents split up, her father relocated to a Caribbean island to hide. He was caught on Wetherall’s twelfth birthday by authorities who tracked him down via the paperwork generated by her visit to him.

This story, and the many emotional narratives that twine around it, are recounted by Wetherall with unusual sequencing. The book is written as a series of non-parallel flashes forward and back. The present day in Cornwall shifts to the mid-1990s in Saint Lucia, which becomes the early 1980s in California, which loops back to the present day in Cornwall. Although the book starts slowly, the storyline soon becomes as exciting as a thriller. A scene in which Wetherall’s mother hides a cell phone inside a couch while the FBI searches the home gallops along with high tension.

In fact, although the action in No Way Home is spurred at each turn by Wetherall’s father Ben, Wetherall’s mother, Sarah, easily emerges as the book’s most fascinating character. She is a determined, prickly, and resourceful woman. Wetherall explains with nonchalance that Sarah was a model and actress in her youth, that she ran off to marry her first husband at sixteen, and that she bargained with Ben that, if she agreed to her son’s circumcision, their second child would take her surname instead of her husband’s. Wetherall’s breezy storytelling paints all this as nearly normal.

But then, nothing is normal in No Way Home. The practical details of Ben living as a criminal in hiding — he smuggled many millions of dollars of marijuana in the 1970s, and eluded authorities for eleven years — are odd enough. But equally unusual are the ways in which Wetherall must reckon with her family as the center of her emotional life. On a prison visit, her father tries to tell her about his decision to marry someone else. But he ends up talking at Wetherall instead, and she tamps down her feelings out of a sense of futility.

He continued to explain to me how I felt, but he was wrong this time, and that made it all the more isolating. Mom and Dad divorcing had fallen way down the hierarchy of problems in recent years, trumped by the FBI and prison; I was upset that I had found out through someone else that he was getting married, and I held on tight to this reason, because if I let it go, I might have to admit that really I was just angry. It was easier to be angry with Dad for marrying Lana than it was to be angry about everything else, and it was easier to resent that he hadn’t told me this one thing, rather than all the other important things he had kept from me.

The memoir is written in plain language, but it delves with grace into Wetherall’s instability as well as her discomfort with the fugitive life. The central part of the volume takes up the smuggling and fugitive actions that sent her family on the run, though the suspense of the book’s final third doesn’t derive from these external circumstances but from Ben’s inability to understand what he has cost his family. Wetherall is the most visible manifestation of that price. A conversation after Ben gets out of prison in 2001 makes the emotional sacrifice clear.

“I know you wish it hadn’t turned out this way—obviously—but really you just wish you’d never been caught, don’t you? You never acknowledge that you shouldn’t have smuggled drugs when you had a young family who needed you…”

Dad had pulled into the driveway of Artie’s house and turned off the engine. He sat back in his seat looking out over the Bay. I saw him struggling, my words hammering away at years of fortified denial.

No Way Home is not as hard-hitting or “brave” as certain splashy memoirs are, but its storyline is unique and intriguing. This is a special family, and for more than just its remarkable history: its members have charm, intelligence, and realistically mixed-up relationships. Wetherall’s siblings provide additional quirk and heft to her story—her sister, Caitlin, has different methods of processing emotion than Wetherall, providing a rounded perspective to the family’s many transitions, and her half-brother, Evan, is both funny and grounded, offering levity and solid advice at the right moments. Through it all, they are loving; Sarah maintains healthy boundaries and is a caring mother, while Ben takes many risks with his freedom just to spend time with his children. In fact, it’s a risk for the sake of family togetherness that gets him caught.

Another memoir about a non-dysfunctional family, no matter how extreme its circumstances, would seem to promise a familiar and placid read. But No Way Home is anything but. In fact, it’s a model for how to tell a weird, complicated story in a way that will make the reader hang on tight for the whole ride.

Katharine Coldiron‘s work has appeared in Ms., the Guardian, the Rumpus, and elsewhere. She lives in California and blogs at the Fictator.