The Arts on Stamps of the World — November 22

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

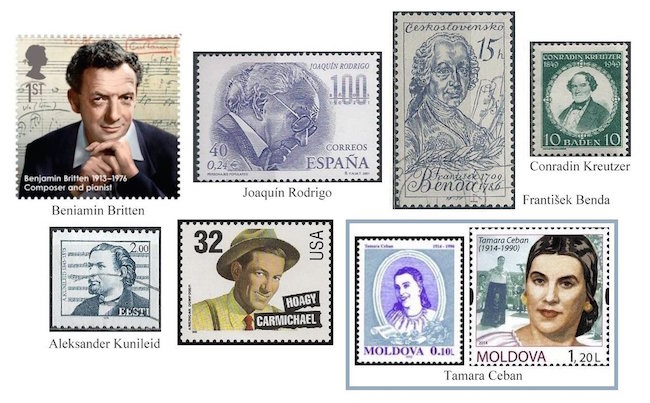

How appropriate that so many distinguished, even great musicians were born on St Cecilia’s Day! Represented on postage stamps of the world are Benjamin Britten, Joaquín Rodrigo, František Benda, Conradin Kreutzer, Aleksander Kunileid, Hoagy Carmichael, and Tamara Ceban, all born or baptized on November 22. Not yet found on stamps are Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and, of course, the late, great Gunther Schuller, who passed away on June 21, 2015. Other prominent classical musicians born on this date are conductor Kent Nagano, pianist Stephen Hough, and organist Peter Hurford.

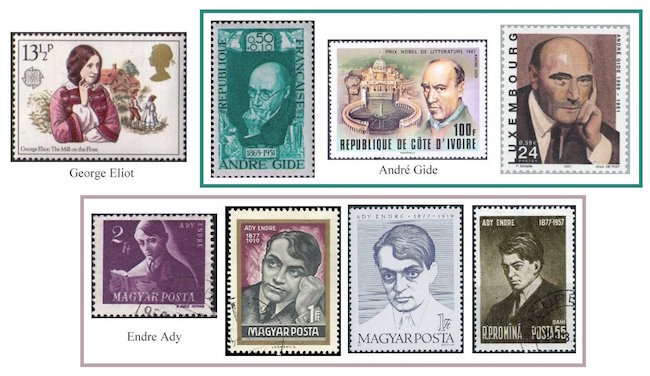

So I thought we’d start our presentation with all the music people before moving on to the other arts, even though we have two very great writers for November 22, George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) and André Gide, as well as the renowned Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias and filmmaker Terry Gilliam.

Of the great composer, conductor, and pianist Benjamin Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976), who wrote so much of my favorite 20th-century music and left a substantial body of superb recordings as a performer, I will simply point out that he wrote a lovely Hymn to St. Cecilia in 1942. The stamp was issued for his centenary four years ago.

Yesterday I spoke of Francisco Tárrega’s childhood injury to his eyes; his countryman Joaquín Rodrigo (November 22, 1901 – July 6, 1999) was almost completely blind from diphtheria from the age of three. His teachers included Paul Dukas. Although Rodrigo’s first published compositions appeared in 1940, his famous Concierto de Aranjuez had been written in 1939 in Paris. His other “best-seller”, the Fantasía para un gentilhombre, was composed for Andrés Segovia in 1954. In 1991, King Juan Carlos bestowed upon Rodrigo the hereditary title of Marquis of the Gardens of Aranjuez. Despite having written so much guitar music (along with many other works), Rodrigo never mastered the instrument himself. He wrote his music in Braille.

Bohemian violinist and composer František (or Franz) Benda was baptized on 22 November 1709. He was the brother of Jiří Antonín Benda, and like him worked for much of his life at the court of Frederick the Great. Besides his compositional legacy, Benda was the founder of a German school of violin playing. For his instrument he wrote 26 concerti, 170 (!) sonatas, 31 duets, and a hundred solo capricci. There are also 17 symphonies. He died on 7 March 1786.

Conradin Kreutzer (or Kreuzer; 22 November 1780 – 14 December 1849) was active at Vienna, Stuttgart (as Hofkapellmeister), Württemberg (as Kapellmeister to the king from 1812 to 1816), and Cologne (conductor of the opera from 1840). Although his works are mostly forgotten today, his 1834 opera Das Nachtlager in Granada (The Night Camp in Granada) held the stage for more than fifty years, and his Septet for winds and strings makes an appearance from time to time. He was one of the 50 other composers (besides Beethoven) who responded to Diabelli’s request for variations on his little waltz.

Estonian choral composer Aleksander Kunileid was born Saebelmann (or Säbelmann) in 1845. His father taught him organ and piano, and the young man continued his studies with the choral composer Jānis Cimze. Around this time Saebelmann, moved by the mood of the Estonian national awakening, dropped his Germanic-sounding name and took up the name “Kunileid” from the motto of Carl Robert Jakobson: “Otsi, kuni leiad” (“Seek, until you find”). It was Jakobson, an important figure in the Estonian movement, who gave Kunileid a prominent role in the first Estonian Song Festival of 1869. Two years later, Kunileid moved with his brother Friedrich Saebelmann to Saint Petersburg, then to Poltava, where he died of heart disease on July 27, 1875, at the age of 29.

Among all these classical musicians we have only one popular music person born on St. Cecilia’s Day, but he’s an icon: Hoagy Carmichael (November 22, 1899 – December 27, 1981). He was born in Bloomington, Indiana, and got his unusual name from an unusual source: a circus troupe called the Hoaglands happened to be staying at the house while Carmichael’s mother was pregnant with him. So it is that he was born Howard Hoagland Carmichael. It was from his mother that he got his earliest musical training. Other than lessons with jazz musician Reginald DuValle, Carmichael had no other instruction in music. He started playing professionally in 1918 and met and formed a partnership with Bix Beiderbecke in 1922. Beiderbecke recorded one of Hoagy’s songs in 1924. Meanwhile, Carmichael was working toward his law degree, earned in 1926. The next year saw the birth of “Stardust”, which didn’t become a hit until 1930. By that time Carmichael was in New York. He started writing songs for Hollywood and in 1937 made the first of his fourteen appearances on screen. His song “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening”, written with long-time lyricist partner Johnny Mercer, won an Oscar in 1951. (I said that Carmichael was not a classical composer, but he did write two orchestral scores, Brown County in Autumn in 1948 and the Johnny Appleseed Suite in 1963, but they did not please the critics.) He worked as the host of radio programs and continued his acting career on television. Over the course of his life he wrote hundreds of songs, and fifty of them were hits.

Tamara Ceban (née Ciobanu, 22 November 1914 – 23 October 1990) was a Moldovan singer of opera and folk music and achieved considerable fame in her native land, which was then part of the Soviet Union. Among her more celebrated roles were Tatiana in Eugene Onegin and Cio-Cio-San (Ciobanu’s Cio-Cio San, of course). She was elected a deputy of the Supreme Soviet! Here’s a link to an old film of her performing a folksong.

On the literary front, one of the great novelists of the 19th century, Mary Ann Evans, better known by her pseudonym of George Eliot, was born on this day in 1819. A homely girl, she was blessed with keen intelligence and given a sound education to compensate for her “unmarriageable” qualities. When her formal education ended at sixteen, she augmented it with voluminous reading. She became a freethinker and translated intellectually probing religious works by such writers as David Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach. In 1851 Evans became assistant editor for the left-wing journal The Westminster Review, a most extraordinary position for a woman in those times. She determined to become a writer and produced essays for the review, though her first book, Scenes of Clerical Life, didn’t appear until 1857. Only with the great success of Adam Bede (1859) did Evans come forward from behind the guise of “George Eliot”. It is gratifying to note that she enjoyed a loving and intellectually enriching relationship with George Henry Lewes for a quarter century, then married a man twenty years younger than herself. At least two of Eliot’s novels have been staged as operas: Silas Marner (1961) by British composer John Joubert, and Middlemarch in Spring by the American Allen Shearer, which just premièred in 2015. Martin Amis and Julian Barnes have called Middlemarch the greatest novel in the English language. I’ve read it twice and would be hard put to disagree. Additionally, there are settings of Evans’s verses by Charles Stanford and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, among others. Mary Ann Evans died on 22 December 1880.

I had a dear humanities professor at UMass Boston by the name of Irvin Stock who loved to recall his meeting as a young man with André Gide (22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951). When Gide himself was a young man of 21 he brought out his first novel, The Notebooks of André Walter (Les Cahiers d’André Walter, 1891). Not long after, he went to Northern Africa and surrendered to his desires for boys. His new friend Oscar Wilde, whom Gide met in Paris, didn’t discourage him. Gide’s marriage to his cousin Madeleine Rondeaux in 1895 was prompted by his deep love for her from childhood and by a genuine wish to provide for her, but the marriage was never consummated; ironically, it was the son of Gide’s best man at the wedding who would much later give him a fuller quasi-conjugal repletion. Outspoken and unafraid, Gide bravely defended homosexuality in Corydon (1924), reported on the abuses of colonialism in Travels in the Congo (1927) and Return from Chad (1928), and renounced his embrace of Communism in no uncertain terms in Return from the U.S.S.R. (1936): “No one can begin to imagine the tragedy of humanity, of morality…in the land of communism, where man has been debased beyond belief.” Among Gide’s other accomplishments was the introduction into France of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim. A prolific writer of fiction, drama, poetry, criticism, autobiography, and travel, he would become a recipient of the Nobel Prize in 1947.

Many readers see Endre Ady (November 22, 1877 – January 27, 1919) as the greatest 20th-century Hungarian poet. He published his first poem at 18 and his first volume of poetry at 21, receiving widespread recognition with his fourth volume, Blood and Gold (Vér és arany), in 1907. The next year, a new magazine, Nyugat (The West) became his home for the remainder of his life—he became an editor in 1912. He wrote much political material as well. Ady’s poetry, which was set to music by Bartók and Kodály, was strongly influenced by Baudelaire and Verlaine. Besides the stamps (one of them Romanian), Ady’s image was also seen on the 500 forint Hungarian banknote of 1975.

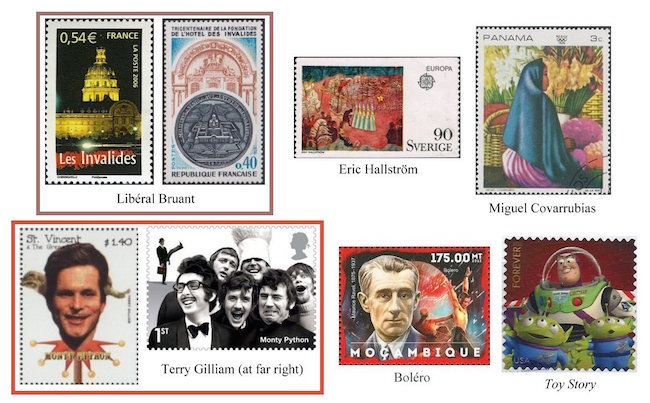

22 November 1697 is the day on which Libéral Bruant died. Born about 1635, he came from a family of French architects spanning the 16th to the 18th centuries, but of them all he is the best known, and his most prominent work, the Hôtel des Invalides in Paris, was a late commission (1670) from Louis XIV. Bruant died before the work could be completed, and the feature that now dominates the whole structure, the dome, was actually designed and built by Jules Hardouin Mansart, who had assisted Bruant from the early stages. On the first of the stamps I’ve chosen to illustrate the edifice, Mansart’s dome towers above Bruant’s pedimented central block at the fore. The other stamp is a more fitting tribute to Bruant, as it portrays both a close-up of the facade, featuring an equestrian Louis, and, on the medallion, an overview of the entire complex. Bruant was one of the first eight members of the Royal Academy of Architecture founded by Louis in 1671.

Swedish artist Eric Hallström (22 November 1893 – 17 June 1946), born in Stockholm, was the son of a lithographer and landscape painter who gave him early instruction before his formal studies in the city. Hallström also painted landscapes but is better known for his street scenes. The stamp gives us Hallström’s New Year’s Eve at Skansen.

Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias (22 November 1904 – 4 February 1957) was known mainly as a painter and caricaturist, but he also worked as an illustrator, art historian, and ethnologist. Born in Mexico City, he began while still in his mid-teens to create illustrations for publications of the Mexican Ministry of Public Education. In 1924 he received a government grant to visit New York City, where he was introduced to critic and photographer Carl Van Vechten and through him to New York’s literary Smart Set. It wasn’t long before Covarrubias was contributing to Vanity Fair. He also designed for the theater, including sets and costumes for Josephine Baker and dancer/choreographer Rosa Rolanda, who would become his lover and, in 1930, his wife. Their friends included Eugene O’Neill, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and W.C. Handy. Covarrubias made book illustrations for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Herman Melville‘s Typee, and Pearl Buck‘s All Men Are Brothers. For the National Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City Covarrubias was invited to establish an Academy of Dance, which he did with the assistance of Rosa, also inviting his friend José Limón to open the inaugural season in 1950. As an art historian, Covarrubias was an expert on pre-Columbian art, in particular that of the Olmecs. I could find none of Covarrubias’s caricatures on stamps and only one painting, Flower Seller on a stamp from Panama.

Today’s last birthday celebrity is another brilliant member of Monty Python, Terry Gilliam (born 22 November 1940). He first saw the light of day in Minnesota, but went to high school and college in Los Angeles. He worked with Pythoners-to-be Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin on the British ITV children’s series Do Not Adjust Your Set (1967-69). Gilliam became a British subject in 1968 and, disgusted with the administration of our 43rd president, renounced his American citizenship in 2006. In the intervening years he went from animator and strip cartoonist to director of phantasmagorical feature films such as Time Bandits (1981), Brazil (1985), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), 12 Monkeys (1995), and The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009). (He co-directed Monty Python and the Holy Grail with Terry Jones.) More recently he has expanded into opera direction with an English National Opera production of Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust (2011). In the What-Might-Have-Been Dept., it seems Stanley Kubrick envisioned that Gilliam would direct a sequel to Dr. Strangelove.

We wind up with two premières: the first performance of Ravel’s Boléro in 1928 and the release of the first fully CGI movie, Toy Story, in 1995.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.