Visual Arts Review: Italian Futurism — The Future That Wasn’t

Futurism, as the Italian proponents conceived of it, ended up not having much of a future. But its practitioners had some good days at the beginning, which merits a visit to the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York through Sept. 1.

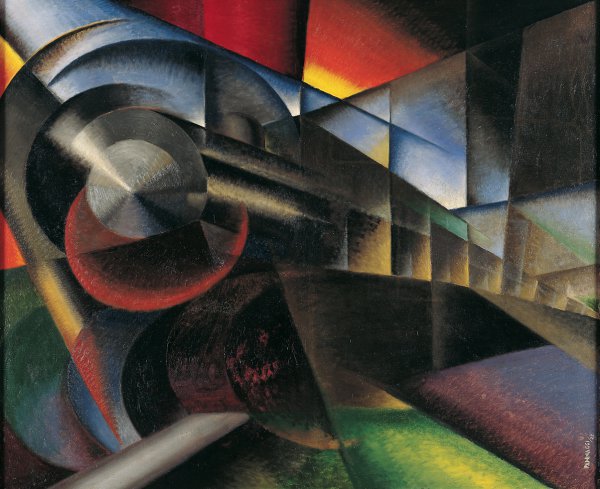

Ivo Pannaggi, Speeding Train (Treno in corsa), 1922. Photo:Courtesy Fondazione Cassa di risparmio della Provincia di Macerata

By David D’Arcy

Entering the ambitiously titled Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe at the Guggenheim, the first form you notice is the container for this show of 360 objects in a range of media – the reverse spiral by Frank Lloyd Wright, completed in 1960.

Wright’s remarkable building is a lot of what the Futurists dreamed of accomplishing – it is revolutionary, daring, provocative, and pure in its aesthetic.

A car could ascend this ramp to the heavens, so the Futurists’ infatuation with the motorized age would be satisfied. Their leader, the calculatingly vituperative F. T. Marinetti, declared that “a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

The Wright structure suggests an industrial form, whether the shape reminds you of a smelter-sized crucible or a modern toilet. And its construction defied old-fashioned approaches to building. The cement was poured continuously, without seams, to create the walls and ramp. The Italian Futurists were nothing if not purists. Or intolerant anti-purists, depending on your perspective: they demanded that old swampy Venice be dynamited. We can assume they would have approved of the Guggenheim’s abrupt, curvaceous jolt to 5th Avenue’s grand facades.

Of course, Wright was not an Italian futurist. More accurately, he was his own kind of futurist, never following anyone else’s manifesto. He did write a few of his own.

Tightly focused, the Guggenheim exhibition revolves around the Italian Futurists, who burst onto the scene before 1910, at the end of the Belle Epoque, which they despised along with everything else that smacked of peace. They had a few imaginative and influential years up to the early days of World War I. After that, what had once been seen as revolutionary became a set style. Their influence faded with the violent end of Italian fascism, which the Futurists supported. At that point, the anarchistic movement was too exhausted to celebrate the downfall of Il Duce.

Futurism, as the Italian proponents conceived of it, ended up not having much of a future. But its practitioners had some good days at the beginning, which merits a visit to the revelatory Italian Futurism, 1909–1944. You may never again have the opportunity to see an exhibition on such a scale devoted to this subject.

The two figures to watch here are Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) and Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916).

Marinetti was the mouthpiece of a movement at first inspired by words rather than pictures. Here are the bullet points of a much longer decree that appeared on the front page of Le Figaro in Paris in February 1909. Marinetti had already said much of the same in Italy. It merits being quoted at length to appreciate its resonance with fascism.

MANIFESTO OF FUTURISM

We want to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness.

The essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity and revolt.

Literature has up to now magnified pensive immobility, ecstasy and slumber. We want to exalt movements of aggression, feverish sleeplessness, the double march, the perilous leap, the slap and the blow with the fist.

We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath … a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

We want to sing the man at the wheel, the ideal axis of which crosses the earth, itself hurled along its orbit.

The poet must spend himself with warmth, glamour and prodigality to increase the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements.

Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.

We are on the extreme promontory of the centuries! What is the use of looking behind at the moment when we must open the mysterious shutters of the impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We are already living in the absolute, since we have already created eternal, omnipresent speed.

We want to glorify war — the only cure for the world — militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.

We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.

We will sing of the great crowds agitated by work, pleasure and revolt; the multi-colored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals: the nocturnal vibration of the arsenals and the workshops beneath their violent electric moons: the gluttonous railway stations devouring smoking serpents; factories suspended from the clouds by the thread of their smoke; bridges with the leap of gymnasts flung across the diabolic cutlery of sunny rivers: adventurous steamers sniffing the horizon; great-breasted locomotives, puffing on the rails like enormous steel horses with long tubes for bridle, and the gliding flight of aeroplanes whose propeller sounds like the flapping of a flag and the applause of enthusiastic crowds.

It is in Italy that we are issuing this manifesto of ruinous and incendiary violence, by which we today are founding Futurism, because we want to deliver Italy from its gangrene of professors, archaeologists, tourist guides and antiquaries.

If this manifesto sounds pompous and grandiloquent, it was – note the ode to industry, the call to bomb museums and the slam on feminism, probably meaning femininity. These were years in which the intelligensia was smitten with visions of political upheaval. Marinetti was far from the only theorist rallying followers, but his fervor ensured that Futurism was stronger in Italy than anywhere else.

True to his guidelines, Marinetti created “works” that were mostly manuals showing how to carry out his mandates – black and white diagrammatic designs (now faded) on paper that rejected Italian traditions of graceful composition and nuanced color. Marinetti flooded Europe with copies of his manifesto. Later, his followers would drop his pronouncements from airplanes, the latter becoming important Futurist symbols of modernity.

Umberto Boccioni, “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space” (Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio), 1913. Photo: he Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Marinetti’s followers were poets and artists who thought culture would be served by burning down anything that was revered as venerable. They also couldn’t wait for World War I to rip Europe apart. In the ’30s, they cheered Mussolini’s bloody invasion of Ethiopia.

If Marinetti was a polemicist, Boccioni, an adherent to Marinetti’s call for noise and cacophony, was a painter and sculptor first, with an imagination equal to his talents for propaganda.

In his sculpture, Boccioni (following Marinetti’s call to arms) sought to capture movement and force in three dimensions. Like other Futurists, he experimented with reducing his subjects to their skeletal elements – the inner machines that animate them.

Some things work better on paper. In the Guggenheim gallery, you can see the paradoxical results when Boccioni’s medium was bronze. In “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space” (1913), vectors of metal veer off from a figure’s ankles, shoulders, and loins. The shapes are curved but oddly stiff, fused to blocks on the pedestal. Instead of motion (or the suggestion of motion), the customary goal of the Futurists, Boccioni gives us monumentality. For the school kids who march up and down the Guggenheim ramps on weekdays, the bronze shape must look like a model for Robocop.

It is a striking figure – an ‘Every-Body’ that updates “Vitruvian Man,” Leonardo da Vinci’s 1490 illustration of the human body. But, in terms of its futurist panache, the piece has at least as much to do with yesterday as with tomorrow, more Victory of Samothrace than a roaring motor car.

Boccioni’s paintings are dedicated to swirls of energy. “The City Rises” (1910-11) is the best and the best-known, although reproductions do not do the picture justice. Its subject is violent change. Its setting is a construction site filled with visual cacophony, an attack by Boccioni on Italian notions of proper pictorial composition. (Fernand Leger also depicted images of construction in France, but not so apocalyptically). The central figure is a winged horse, red as if afire, hauling out building materials for new structures, tossing men aside in the process. Boccioni gives us a violent micro-crucible out of which is born the new, dragged into being by an animal of the old order that’s consumed by the process of creation. All its creatures – men and horses — are fused together, essentially draft animals playing a part in evolution. The painting was an act of provocation, although note that Boccioni couldn’t let go of an image from Greco-Roman mythology.

Boccioni could do more than depict what looked like the blast furnace of change. (His fixation with a fiery palette was shared with fellow Futurist Carlo Carra, whose dark “Funeral for the Anarchist Galli” (1910-11) looks more like a wild riot than a memorial vigil.) Boccioni departed from the rules in the movement’s iconoclastic manifesto, painting contemplative, even intimate, experiments in color and abstraction (he called them “States of Mind”). He was growing out of the Futurism before his death in 1916, thrown from a horse in a cavalry training exercise. Ironically, he was killed the creature at the center of “The City Rises.” His life ended at the service of a military unit destined to be automated out of existence.

Once Italian Futurism lost its greatest talent, the revolutionary party began to wind down.

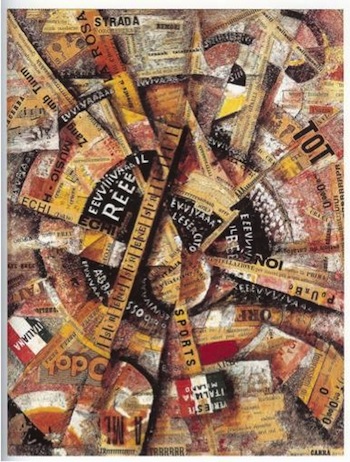

Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Demonstration (Manifestazione Interventista), 1914. Photo: Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

By 1916, Futurists abandoned the cacophony Marinetti mandated, reverting to the harmony and (God forbid) decorative grace that pure Futurism condemned. They may have found their inner bella figura, but Marinetti hadn’t given up imposting control: he wrote an imperious treatise about how to seduce a woman. Guido Severini’s military scene, “Armored Train in Action” (1915), features a railway car filled with faceless, pale blue riflemen. Each side of the track is bordered with green flora, an improbably mild color palette for a scene of war, even given its suggestion of mortality. Les fleurs du mal? Not quite. To our eyes, the picture comes off as war-lite. Given the newspaper photographs of corpses that Serverini’s contemporaries saw every day, this image probably looked improbably soft-focus back then.

These soft-focus pictures point to Futurism’s future, an evolution from provocation to decoration. Still, the kinder and gentler art that broke away from Marinetti’s dogmatic mandate charms the eye.

“Speeding Motorboat” (1923-4), a pattern of geometrical swirls in the wake of a boat on the distant horizon, is a bold but graceful composition in blue and gold, an ode to speed and motion that isn’t in the least threatening. The painter was a rare woman in the movement, Benedetta, the nom de guerre of Benedetta Cappa, who became Benedetta Cappa Marinetti when she married the voice of Futurism in 1924.

Ten years later, Benedetta painted “Syntheses of Communications,” a series of murals for the Palermo post office – huge dreamy canvases in pastel colors celebrating such Futurism-appropriate activities as communication via telegraph, telephone and radio. In a major coup, the murals are at the Guggenheim, at the top of Wright’s spiral. A Futurist to the end, Benedetta’s husband saw “dynamism” in these elegant images. The less dogmatic among us will see a hypnotically seductive lyricism.

As the edge of Futurism softened, so did its political belligerence. Soon after World War I, Futurists were developing the vocabulary of advertising. Selling out? They were shamelessly selling products, as we see in the work of Fortunato Depero (1892-1960), a puckish designer of everything from theater sets to toys to tableware to magazine covers to fascist propaganda. And yes, there were Futurist evening dresses.

The Futurist core of Depero’s work lies in its visual language, based on minimalist modules which could be used to shape figures, animals, and landscapes, even a folkloric scene of dancing devils in Halloween reds and oranges. Depero, who traveled to the US, gave Futurism a much-needed sense of humor. You can see it in his clever ads for Campari. You can also sample a blithe application of his imagery in the service of glorifying Il Duce in his mural-sized study for a mosaic, “Proclamation and Triumph of the National Flag” (1935). Note: the self-proclaimed rebels of Futurism are viewed as courtesans.

Installation view — Italian Futurism, 1909–1944, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: Kris McKay

Italy was not Germany, and Italian fascism did not persecute artists for ‘degenerate’ artistic styles, as the Nazis did. Futurists routinely paid tribute to Mussolini in paintings and sculpture. Yet for all their striking servility (bravado should not be mistaken for courage or independence), the Futurists fared badly when they submitted their conventionally modernist designs for government buildings, which was where the real money was at the time. Futurists lauded fascist creative destruction in their pronouncements and in their art, but the Fascist regime preferred structures and monuments to be Roman-style, decorated with columns and classical architectural elements that Marinetti and friends despised.

By 1944, when Marinetti died, Mussolini had been ousted (partisans would execute him in 1945) and Futurism had been largely discredited, even though, ironically, the war had destroyed some of the classical architecture that the Futurists had dreamed of demolishing.

The movement’s aesthetic legacy is elusive as you walk back down the Guggenheim ramp after taking in Benedetta’s celestial murals. Yes, the Futurists lived up to their anarchistic marching orders: they shattered images and forms, fragmented photographs, and simulated movement. But artists throughout Europe were undercutting traditional art before World War I. There was one extraordinary Futurist artist, Boccioni. He was surrounded by lesser lights who lived to heed the call of Marinetti. The movement produced plenty of experimentation, but few masterpieces.

Thus Futurism, for all its chummy worship of world-dominating power and warmongering, was essentially a treadmill back to the future. The movement’s most noteworthy works after 1916 were tasteful paintings that betrayed the crude machismo of the initial manifesto. Futurism’s conservative fate was to be displayed in museums, the very institutions that had been in its cross-hairs.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

The phrase “Futurism, as the Italian proponents conceived of it, ended up not having much of a future.” is arguably nonsensical. Every artistic movement is active for a rather short period of time and could therefore be said not to have a future. Hence why it is called a movement. If what you meant to say was that futurism was not a successful movement, then you would still be wrong. Futurism marked a change in art and reflected the big changes in society, the new era of industry and technology. I don’t agree with the Futurism Manifesto, I don’t support it and I don’t even like futurist art, but I still don’t agree with this affirmation. This was part of our artistic evolution and I don’t see the point in discrediting it.

“Futurism had been largely discredited, even though, ironically, the war had destroyed some of the classical architecture that the Futurists had dreamed of demolishing.” Why “Ironically”? Obviously the whole point of art is to see beyond, art is always an anticipation of what is going to happen. No surprise there.

“The movement produced plenty of experimentation, but few masterpieces.” Nothing wrong with this, experimentation is a key aspect of the artistic endeavour.

“The movement’s most noteworthy works after 1916 were tasteful paintings that betrayed the crude machismo of the initial manifesto.” It is fine for an artistic movement to evolve and change, especially if a world war enters the picture.