Music Interview: Jazz Colossus at 80. Bob Blumenthal on Sonny Rollins

Bob Blumenthal has spent almost his entire listening life as an admirer of Rollins and an appreciator of his music, and he is a prose stylist of great elegance and precision. There is hardly anyone alive more qualified to write this kind of career-spanning appreciation.

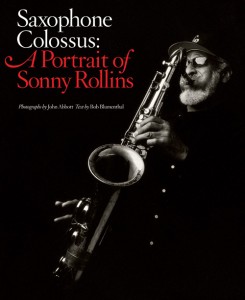

Saxophone Colossus: a Portrait of Sonny Rollins Text by Bob Blumenthal. Photography by John Abbott. Abrams, 160 pages, $35.

Saxophone Colossus: a Portrait of Sonny Rollins Text by Bob Blumenthal. Photography by John Abbott. Abrams, 160 pages, $35.

By Steve Elman

Here is the second part of the conversation.

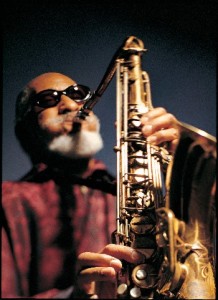

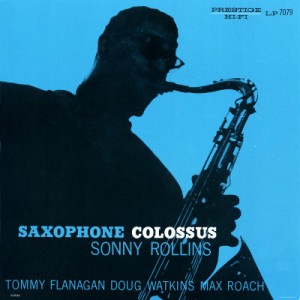

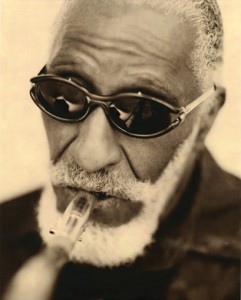

Sonny Rollins turned 80 on September 7. The book Saxophone Colossus: A Portrait of Sonny Rollins celebrates that milestone with five deeply perceptive essays by jazz critic Bob Blumenthal ruminating on the five tunes of Rollins’s classic 1956 LP with the same title. It is equally the work of photographer John Abbott, whose 110 luminous portraits of Rollins (along with studies of Sonny’s working band, Miles Davis, Max Roach, pianist Tommy Flanagan, and Rollins’s long-time bassist Bob Cranshaw) are interspersed through the text. Abbott’s award-winning jazz photography has been featured on more than 250 album and magazine covers. He has been the primary cover photographer for JazzTimes magazine since 2003

The design of the book is essential to its purpose. It fosters a front-to-back appreciation: words, then images, then words.

You will see nothing radical about it at first. As in so many coffee-table books, text and pictures alternate irregularly. In one chapter, there is a single photo followed by a single page of writing. At another point, there are two pages of text followed by seven photos. Saxophone Colossus shows off a nice variety of forms as it progresses—some pages of print are in large font and others in small; some photos are bled to the edges and others are framed in white space.

But whenever the essays are interrupted for images, the designers, David Groom and David Meredith, have taken care to end the page preceding the photographs with the last words of a paragraph, so that the reader is not led overleaf by a running sentence. Also, in nearly every case, they have tried to break the text at the conclusion of one of Blumenthal’s thoughts.

This approach helps the reader overcome preconceived notions of “reading the essays” or “looking at the pictures” as separate means of perception. It puts the brakes on the reader’s momentum, interrupting the progress through the book the way a zigzag breaks the path in a Japanese garden. Abbott’s pictures are not there to illustrate Blumenthal’s words. They give the reader a place to stop, to breathe, to think about Sonny Rollins.

Blumenthal has spent almost his entire listening life as an admirer of Rollins and an appreciator of his music, and he is a prose stylist of great elegance and precision. There is hardly anyone alive more qualified to write this kind of career-spanning appreciation. Saxophone Colossus fulfills the promise of this lifetime of study, and, at the same time, it rewards the reader with a purely visceral pleasure.

Our conversation circled around two poles, and I have edited the give-and-take into two parts. This segment focuses on Rollins’s music and personality. Note: Rollins’s 80th birthday concert will be in New York (September 10, 8 PM, at the Beacon Theatre) with guitarist Jim Hall, bassist Christian McBride and trumpeter Roy Hargrove, as well as special guests.

ArtsFuse: Abrams has posted a video of you and John [Abbott] talking about the book. In that conversation, you said, “Sonny did find an answer sort of halfway along in his career.” What did you mean by that and what was the answer?

Bob Blumenthal: To my mind, the question for Sonny was: how to function as a creative artist, given the economic, social, [and] cultural impediments [that face] an African-American jazz musician.

And, at various stages, his answer was to simply go away [that is, to take a hiatus from performing] and deal with it. He had a drug dependency; he went on sabbatical. He had some self-doubts about his own playing; he went on sabbatical. He had frustrations with the economics of the music business, record labels, and night clubs; he went on sabbatical.

When he returned for the final time, which was 1972, when he was 42 years old—and the last chapter of the book [“Blue 7”], which is subtitled “Sonny’s Theme,” deals with this—I think he found the solution or solutions.

One was that he and Lucille [Sonny’s wife] moved to upstate New York, where he was able to focus more exclusively on music. Lucille became his manager. The way they lived their life every day was Sonny would go into his studio, he’d practice and exercise and write music, and Lucille would stay in the main house and do all the business.

He also obtained a recording contract with Milestone that really gave him much more freedom in when he would make records, what kind of records he would make. He could do his recordings his way.

When you put these things together, I think it brought him to the point where he realized he didn’t have to keep dropping out because of frustration with one thing or another about his life and working conditions, and that he could get to the point where his music could be presented on the same level that Yo-Yo Ma’s music is presented or Vladimir Horowitz’s music was presented, and that he could play in the kind of venues that he felt the music deserved. So when I say “He figured it out halfway along,” that’s what I had in mind.

Blumenthal is a highly respected jazz writer. Over a 41-year career, he’s won two Grammys for album liner notes and a lifetime achievement award from the Jazz Journalists Association.

His first features and columns appeared in Boston after Dark in 1969, and they continued there for 20 years, through and after the paper’s transformation into The Boston Phoenix. The strength of that work led The Boston Globe to tap him as guest reviewer for the Boston Globe Jazz Festival in the late 1980s and ultimately to hire him as a regular writer (1990–2002). From 2002 to 2009, he was creative consultant to Marsalis Music, Branford Marsalis’s record label. In addition, he has contributed notes to dozens of LPs and CDs and authored pieces for many marquee music publications.

His first book, Jazz: an Introduction to the History and Legends behind America’s Music, was published by Smithsonian/Harper Collins in 2007.

Little-known biographical tidbit: he was a winning contestant on The $20,000 Pyramid. He lives in Newton, Massachusetts.

AF: It’s been six years since Lucille’s death. Is there anything that you’ve seen that is different in the way that Sonny lives his life today?

Blumenthal: I think that he’s more open to participating in things that aren’t just straight concert performances. He’s going to attend our book signing in New York City [Tuesday, September 14, 7 p.m., at the Tribeca Barnes & Noble, 97 Warren Street, NYC]. He did an on-stage interview with me in Burlington, Vermont this summer.

With Lucille not there, I mean, he’s up in the country, he’s off by himself. The Minguses [bassist – composer Charles Mingus and his wife Sue] had a place up there before Charles passed away, and [drummer] Jack DeJohnette and his wife are up there, and there was a little circle of social interaction. I think he misses that, among many other things, and that’s led him to get out in the world a little more.

I don’t think it’s affected the music, though.

AF: How often do you hear him play live these days?

Blumenthal: It’s been amazing. I saw him last month, and I said, “I’m becoming your stalker.” In the last year, I’ve heard him perform four times, and I will hear him for a fifth time in a 12-month span at his New York concert [part of Rollins’s 80th birthday celebration tour, September 10, 8 p.m., at the Beacon Theatre; see description below].

AF: Do you ever think, “Oh, he’s different from the way he was five years ago or different from the way he was 10 years ago, or different from the way he was 20 years ago?”

Blumenthal: Not so much in how he’s approaching playing as in the band and the music he chooses to play.

But I don’t quite look at it that way. I think that’s one of the questions that deserves more thought from people who love jazz. Does a great artist have to be constantly changing? I think a lot of the controversy about [the jazz programs at] Lincoln Center was around this notion: “Is art something you perfect and find the ideal and present [that is, display or perform], or does it just have to change all the time?”

But I don’t quite look at it that way. I think that’s one of the questions that deserves more thought from people who love jazz. Does a great artist have to be constantly changing? I think a lot of the controversy about [the jazz programs at] Lincoln Center was around this notion: “Is art something you perfect and find the ideal and present [that is, display or perform], or does it just have to change all the time?”

I think that if you look at the falling out that Willem Breuker [Dutch reedman-composer, 1944–2010] and Misha Mengelberg [Dutch pianist-composer, 1935-] had in Holland [in the early 1970s, as co-leaders of the Instant Composers’ Pool], it’s a lot [like this]. Breuker [later known as the charismatic leader of the Willem Breuker Kollektief] wanted to sort of create this show where everybody was very precise and on the money, and Mengelberg, whose whole aesthetic is “What can I do throw you off?” [saw things very differently].

AF: Much has been made of Sonny’s sense of humor. Can you be specific about the nature of that sense of humor?

Blumenthal: Well, I just think it’s his overall approach. The first time I interviewed him we talked about this, and he said, “It’s just your personality, and you can’t demand that everyone display humor when that is not their personality.”

He mentioned that many people have told him that they felt he was not serious enough, and that after he recorded “Tenor Madness” [a famous performance co-featuring John Coltrane; from Tenor Madness: Prestige, 1956, reissued on CD in 1990], Coltrane said to him, “Oh, you were just playin’ around.” But to me, “Tenor Madness” is a perfect example of how musical personality gets expressed. Coltrane, while not humorless, was relentlessly serious. So, when [the two saxophonists, Coltrane and Rollins] get to the part of the four-bar exchanges, on two or three [of them] Coltrane just belabors this scale passage over and over. Finally, in response, Sonny plays it backwards. Those are [just their] personality traits.

AF: A propos of that, one of my favorite Sonny moments is where he quotes “You Oughta Be in Pictures” when playing “It Could Happen to You” [from The Standard Sonny Rollins: RCA, 1965; reissued on CD in 1999 and in a multi-CD set, Original Album Classics, in 2010]. If you’re not thinking about what he’s doing, it’ll go right by you. “You oughta be in pictures! It could happen to you!” There’s an actual relationship between the titles, and that’s a very high order of humor.

AF: Another thing that is constantly mentioned about Sonny’s work is what Gunther Schuller called “thematic improvisation.” Many, many [jazz] musicians use motifs and excerpts of the theme [in their solos]. What’s different about the way Sonny takes the theme apart and works with it in his solos?

AF: Another thing that is constantly mentioned about Sonny’s work is what Gunther Schuller called “thematic improvisation.” Many, many [jazz] musicians use motifs and excerpts of the theme [in their solos]. What’s different about the way Sonny takes the theme apart and works with it in his solos?

Blumenthal: I think that he will sustain the reference, if you will.

In “Blue 7,” just about everything he plays can be traced back to a little melody which was improvised in the studio. The “composition” part of that piece was Sonny saying, “Here’s the key we’re going to play in, here’s the tempo, and here’s the order we’ll solo in. Now let’s go. Doug [Watkins, the bass player], walk a chorus, and we’ll see what happens.”

In the most recent interview I did with him, we talked about it a little. He said, “You know, I’m just a logical person. That’s just the way I think.” He’s been quoted many times as saying he didn’t realize what he was doing until Gunther Schuller wrote about it [“Sonny Rollins and the Challenge of Thematic Improvisation,” Jazz Review, November 1958], but that’s the way his mind works. And as a result, he can sustain that kind of referential approach to playing in a much more extended frame than other people do.

AF: It’s probably likely that no drummer who’s worked with Sonny has had as important a role in his music or was as creative a fire [for him] as Max Roach was. I wonder why you think that is, first of all. And secondly, do you think that Sonny is unwilling [at this point in his career], to confront a major talent, say a [drummer] Roy Haynes, or a Jack DeJohnette? Does he prefer to work with people who are “second” to his genius? Or would he embrace the idea of real give-and-take with someone who’s on the same plane?

Blumenthal: I think his encounter with Max came at a very pivotal time in his career. He had just overcome his drug dependency. He had been acknowledged as a creative force but hadn’t really established himself to the point where he was a bandleader. By working in Max’s band for almost two years, it gave him the confidence to stand on his own two feet as a bandleader.

[As for the other question,] he has made albums with Jack DeJohnette [Sonny Rollins’ Next Album, 1972; Reel Life, 1982; Falling in Love with Jazz, 1989; three tracks on Here’s to the People, 1991; Old Flames, 1993; two tracks on Sonny Rollins + 3, 1995; four tracks on This Is What I Do, 2000; all released on Milestone]. But, in the chapter on “St. Thomas,” I talk about his dissatisfaction with drummers and how many great drummers have had short-term relationships with him.

I think part of it is, once he reached the point where he could function as he chooses—for example,] his summer [2010] tour was three festivals in Europe, then he’s playing New York in September, then he’s in Japan in October, then he’s doing four or five concerts in Europe in November—that’s irregular enough so someone like Jack DeJohnette’s going to have a hard time committing to that kind of schedule.

AF: If Sonny had the chance to do a session with Roy Haynes, would he do it?

Blumenthal: Well, they played together at Carnegie Hall in 2007. They played three tunes. [You remember that] tapes of Coltrane and Monk at Carnegie Hall were discovered at the Library of Congress from a quite extravagant concert [in 1957] where four or five other bands played [Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall: Blue Note, 2005]. Sonny performed that night with, I think it was [bassist] Wendell Marshall and [drummer] Kenny Dennis, and they played three trio numbers [as yet unreleased].

His Carnegie Hall concert in 2007 was in two parts: the first part was Sonny, [bassist] Christian McBride, and Roy [Haynes], playing the same three tunes he had played 50 years earlier, and then after intermission it was Sonny’s current band. [There are pictures in Saxophone Colossus of Rollins, McBride, and Haynes at the time of that concert].

[Also,] he’s got this 80th birthday concert in New York [September 10, 8 p.m., at the Beacon Theatre, with guitarist] Jim Hall, [bassist] Christian [McBride], and [trumpeter] Roy Hargrove as special guests, and they say more may be on the way. It wouldn’t surprise me if Roy [Haynes] showed up, if he were available. Roy and Sonny go way back to the Bud Powell recordings of 1949.

AF: As far as you know, Sonny has no reluctance about working in these sorts of situations, and he would work with anybody, if he thought it would be artistically valid and satisfying?

Blumenthal: Yeah, but just because we hear things one way doesn’t mean he does. I remember a piece that Francis Davis wrote once, when Sonny said, “Somebody recommended this guy [a young drummer], because my regular drummer can’t perform. We’re playing next week.”

And Francis was singing the guy’s praises. Then a few weeks later, he saw Sonny again, and he said, “Well, how did that work out with . . .”

And Sonny said, “Augh! Horrible, terrible!” And of course, we didn’t hear it, we don’t know. But he hears things his way, so we’re never quite sure where that leads him.

AF: In the interview that you and Sonny did with Tom Ashbrook on WBUR, Sonny said that, while Lucille was alive, she guarded against private recordings, and he’s embraced that more since she passed away, to the extent that one of his most recent releases consisted entirely of concert performances privately recorded by individuals in the audience.

Blumenthal: The backstory on that, as I understand it, is that one of his biggest fans took on a personal mission of collecting as much of this material as he could and presented it to Sonny, and said, “Here, you should have this stuff.”

His attitude about what music will be released without his permission has not changed at all. I said, when we were working on the book, to John, “One of the things that’s most interesting to me is that you could publish the most unflattering photograph, I could say the nastiest thing, and it would mean less to Sonny than if someone released some music of his that he did not approve of.”

AF: I remember being backstage [with him]—the only time I ever MCd a Sonny Rollins date. Sonny was like an island of calm in the middle of the pre-concert chaos. Is that something that you’ve noticed? Does he have an inner centering that keeps him focused on his own goals and distanced from what’s around him?

Blumenthal: I think that that’s part of his day-to-day approach to life.

He doesn’t like tours where he’s playing one night here and the next night somewhere else. He likes to get to town a couple of days early. Any interviews or any kind of activity cannot take place the day of the performance. He’s extremely focused the day of the performance.

[For example,] in Perugia, his band did a sound check at 4 p.m.; the concert was scheduled to start at 9:30 p.m. When the sound check ended, his band went back to the hotel. He stayed at the venue in the dressing room and practiced, he said, in part because he’d been in the hotel for two days and he couldn’t practice in the hotel.

Particularly on the day of performance, it’s very controlled, and I can only assume that time has taught him this is the way he can get the most out of his skills, by doing it that way.

AF: Also in the WBUR interview, Sonny talked about “trying to find perfection” as a philosophical theme in his life. What do you think that means for him musically?

Blumenthal: I’d have to be inside his head to know. When I saw him last month, I went backstage, and I said, “The sound is great, the way [conga player] Sammy [Figueroa] and [drummer] Kobe [Watkins] work together is great, the clarity is fantastic!” and he said, “Calm down. Calm down. Don’t get so excited. We’re going in the right direction. We’re not there yet.”

So he obviously is able to apply standards that are personal. He’s said that he thought Saxophone Colossus was a good day in the recording studio, but he prefers Sonny Rollins Plus 4 [Prestige, 1956; reissued on LP as 3 Giants!; reissued on CD in 1991 and 2007].

If you step in and say, “Ah, we know better, Sonny. That’s good enough, go no further,” you’re inhibiting his ability to reach plateaus you can’t even imagine.

Tagged: Bob Blumenthal, Jazz, Music, Saxophone Colossus, Saxophone Colossus: A Portrait of Sonny Rollins