Visual Arts Review: London’s “Paul Klee: Making Visible” — Endlessly Inventive

Few artists in history have been as multifarious and prolific as Paul Klee – only Picasso and Ernst come to mind.

By John Engstrom

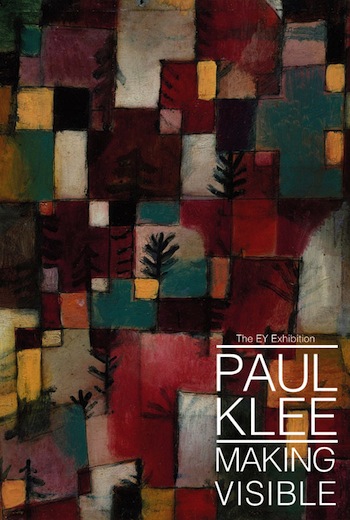

I don’t always think of Paul Klee’s artwork, revolutionary and inventive though it is, as being especially Surrealist – though I know the original Surrealists included Klee in their 1925 debut exhibit in Paris. And Klee was praised in print by leading minds in the movement. Surrealism’s founder Andre Breton noted Klee’s use of “free” or “automatic” drawing techniques, and poet Louis Aragon wrote: “One does not know whether to prefer the delicacy of his watercolours or the ceaseless invention of his drawings.”

I don’t know if Klee himself ever left a statement concerning his relationship to Surrealism. But if there was an affiliation between him and that school it clearly didn’t last long, for Klee has turned out to be one of those omnivorously gifted artists, “not for an age but for all time,” who can’t be boxed into a style, category, or school without cramping their genius.

But I certainly agreed with Aragon about the “delicacy of his watercolours” and the “ceaseless invention” of his drawings when I explored Paul Klee: Making Visible, a retrospective art museum exhibit blockbuster that’s now at the Tate Modern (through 9 March) in London.

In fact, I was blown away by them. The industry, ingenuity and technique that they represent are stupendous. Few artists in history have been as multifarious and prolific as Klee – only Picasso and Ernst come to mind. The exhibit’s seventeen crowded galleries merit a leisurely stroll, and the wall texts are helpful and well written. So what if Dr. Jonathan Miller didn’t like it.

There’s a certain amount of eye-strain as you go through the exhibit at first given that so many of the pieces are small and intricate, but they get bigger as you go along. In Gallery 6 there are outstanding images with enigmatic, private forms and glowing, earthen colors. And “Battle Scene From the Comic-Fantastic Opera ‘The Seafarer'” (1923), oil-graphite-watercolor-gouache on paper, is one of the few pieces in the collection that reflects Klee’s keen interest in the performing arts, whether it was opera, theater, or the circus. He was a profligate polymath.

Curated by Matthew Gale and Flavia Frigeri, the show takes a chronological overview of Klee’s history and aesthetics. A time-based, instead of a thematic, approach enables us to witness the evolution of Klee’s craft and ideas as traumatic history unfolded and exploded around him. It’s also enlightening about his creative wanderings into different techniques – I hadn’t known much about “abstract pointillism” or even Klee’s better known oil transfer paintings until I saw this London group.

Ships in the Dark, by Paul Klee. One of the paintings in the exhibition “Paul Klee: Making Visible” through March 9 at the Tate Modern.

One of my favorites of the work on display, “Fish Magic,” dates from 1925, the year of the Paris show. It evokes children’s art, still life, etching, and a Surrealist mindset – among the images are a floating clock and a swarm of ingenious, vibrant fish. We don’t know if we’re under water, or in a supernatural garden at midnight – there’s no indication of water.

Another fave of mine, “Forest Witches” (1938) from the Nazi period, evokes pictogram and labyrinth with the barest suggestion of female form (a pair of drooping breasts) and an overall mystery that challenges you to fathom it. It’s oil on paper on burlap, evidence of Klee’s creativity when it came to combining materials.

And titling his works! Among the more cryptic or titillating titles at the Tate are: “Primeval-World Couple,” “City Between Realms,” “Six Thresholds,” “Harmony of the Northern Flora,” “Project for a Garden,” and “Ghost of a Genius.”

This was the third Klee exhibit I saw in little over a year – the other two were at Boston College (Arts Fuse review) and in Rome, Italy. An article combining all three looks at Klee is inviting.

John Engstrom is a writer, photographer and collagist who lives in West Fenway. For the last two years he has been writing (and posting on Facebook) a cultural diary of film, opera, visual art and theater. He has been a second-string theater newspaper critic (for The Boston Globe) and a museum role player (at Plimoth Plantation, where he also did photography and video for the Media Department). His drawings, collages, assemblages and photographs have been exhibited at The Outpost and Zeitgeist Gallery. He holds degrees from Boston University and Tufts University (his master’s thesis for the latter was Poisoning: A Cultural Autopsy).