Short Fuse Book Review: “Zealot” — Jesus as Jewish Peasant and Revolutionary

I am a secular Jew who can’t but welcome Zealot‘s conclusion that Christianity pulled a role reversal on Jesus, and made this failed revolutionary Jew into someone who eschewed his people and its traditions in favor of Roman power.

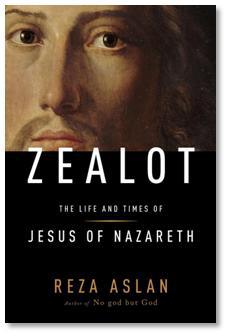

Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth by Reza Aslan. Random House, 336 pages, $27.

By Harvey Blume.

The responses, to date, to Reza Aslan’s concise, suggestive study—Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth—have been of two kinds. There is, to start with, the Fox News kind of response, which, inflammatory and uninformed as it is, can still generate enough faux controversy to blunt attention to what might be deemed genuinely controversial about Aslan’s book.

The Fox interchange, which immediately went viral online, begins with Lauren Green, Fox’s religion correspondent, challenging Aslan: “I want to be clear, you are a Muslim. So why did you write a book about the founder of Christianity?”

For a fraction of a second, Aslan seems nonplussed before responding that he, too, wants “to be clear” and that he is “a scholar of religions with four degrees, including one in the New Testament, and fluency in biblical Greek, who has been studying the origins of Christianity for two decades, who also just happens to be a Muslim.” The interchange continues in this vein, with Green questioning Aslan’s motives and Aslan restating both his unimpeachable academic credentials and the fact that they dovetail with a lifelong interest in the subject matter.

Green has had her defenders on the religious right, but by and large, she has taken a drubbing from the media for hosting a discussion about Zealot that managed to steer clear of anything pertaining to its contents. Following the interchange, Random House rushed another 50,000 copies of Zealot into print. The book, at this writing, sits atop the NY Times nonfiction bestseller list and is near that same position on the Amazon.com list.

Those curious about Aslan’s personal religious trajectory, and why a Muslim might have devoted himself to the copious amounts of research synthesized so well in Zealot, will get satisfaction from the Author’s Note with which the book begins. Its first sentence reads, “When I was fifteen years old, I found Jesus,” and continues, “For a kid raised in a motley family of lukewarm Muslims and exuberant atheists, this was truly the greatest story every told.”

We learn that Aslan’s family fled Iran when the Islamic Revolution of 1979 put Ayatollah Khomeini in power, at which point “religion in general, and Islam in particular, became taboo in our household.” With the economy of expression that has earned him praise as a prose stylist, Aslan adds that in the United States, “our lives were scrubbed of all trace of God,” and, furthermore, that “In the America of the 1980s, being Muslim was like being from Mars. My faith was a bruise . . . it needed to be concealed.”

Then, as a faith-free teenager, a year into college, Aslan attended a summer camp where he encountered the Jesus who became a “best friend, someone with whom I could have a deep and personal relationship.” Becoming a Jesus freak had a social dimension as well, since “accepting [Jesus] into my heart was as close as I could get to feeling truly American.” That said, Aslan emphasizes that his was no “conversion of convenience.” He burned with “absolute devotion to my newfound faith” and armored himself with arguments against those who cast doubt on the literal truth of the gospel stories.

Still, as he pursued academic studies, doubt crept in. The disparity between the gospel accounts and the findings of historians about Jesus and his age became too great for him to resolve by leaps of faith. Aslan turned back toward “the faith and culture of my forefathers, finding in them as an adult a deeper, more intimate familiarity that I ever had as a child.” But his academic pursuits led him, again, to Jesus—not the “detached, unearthly being I had been introduced to in my church” but the “Jewish peasant and revolutionary who challenged the rule of the most powerful empire the world had ever known.” That Jesus is the focus of Zealot.

Aslan has often said there’s nothing particularly new in his version of things. He told the NY Times, “What I’ve done is take this debate that scholars are immersed in and simply made it accessible to a nonscholarly audience. It’s something I wish more scholars would do, in various fields.”

That may be so, while also being disingenuous. Between defending Aslan from Fox News and applauding him for a work of scholarly compression and literary finesse, it’s easy to miss the fact that Zealot comes equipped with a razor sharp polemical edge, one that aims to cut back to the Jewish Jesus from what Christianity has made of him.

“Simply put” is one of Aslan’s favorite ways to begin a bold statement, as in “Simply put, crucifixion was more than a capital punishment to Rome; it was public reminder of what happens when one challenges the empire.”

Simply put, then, Aslan’s chief point is that the suppression of the Jewish Revolt in 70 C.E.—a calamity of incalculable proportions for the Jewish people, especially those who had dwelled in Jerusalem, which was razed and depopulated by Roman forces—served, at the same time, as a birth pang for Christianity as it came to define itself. Judaism, so far as Rome was concerned, was a pariah religion, and Jews the “eternal enemy of Rome.” The followers of Jesus (crucified circa 33 C.E.), scattered by then throughout the Roman Empire, with a key outpost in Rome itself, endeavored to scrub—to borrow another of Aslan’s elocutions—Jesus of his Jewishness. He is no longer one of the mass of Jews who detested the alliance between Roman rulers and the Temple’s high priesthood.

Aslan characterizes this arrangement as nothing less, “for all intents and purposes,” than “a temple-state,” which, between the tithes imposed by the priesthood and the tribute owed to Rome, drove the Jewish masses to seek salvation from a slew of bandits cum messiahs. Jesus, as construed by Christian followers after the Jewish Revolt, was never interested in purifying the Temple and freeing it from the grip of Rome; no, he opposed the institution entirely and wished it destroyed.

Momentously, for the direction Christianity took—and the “two thousand years of Christian anti-Semitism”—Rome is deemed, by Diaspora Christians of the time, to be innocent of Jesus’s death. It is Pilate, the Roman governor, who is depicted as wanting to spare this poor deluded Jew, and the Jewish High Priest who demands his death. Aslan tears this story to pieces: Pilate ordered the crucifixion of self-proclaimed messiahs by the hundreds. They proliferated in an age rife with the expectation of a Kingdom of God that would wipe Judea clean of the reign of the Ceasars: “To call oneself the messiah at the time of the Roman occupation was tantamount to declaring war on Rome.” Pilate was unhesitating in response to messiahs. Nor would such a high Roman lord have thought to interrogate Jesus in person, as Christian legend has him do.

After the Jewish Revolt, Jesus ceases to be the lower class Jew from the Galilee who could neither read nor write Aramaic, his only spoken tongue; nor yet Hebrew, the holy language employed by scribes and in Jewish rites; and certainly not Greek, language of the Hellenized elite. And yet it is in Greek that the chief discourse about Jesus then proceeds, amplified by men “immersed in Greek philosophy and Hellenistic thought,” who “reinterpret Jesus’s message so as to make it more palatable both to their fellow Greek-speaking Jews and to their gentile neighbors in the Diaspora.”

In the process, Jesus ceases to be “a revolutionary zealot” and becomes “a Romanized demigod.” He is transformed from a man “who tried and failed to free the Jews from Roman oppression to a celestial being wholly uninterested in any earthly matter.”

That Zealot is polemical should be abundantly obvious; Aslan has his points to make, but he is never didactic. The book is rich with detail about life among Jews in Jesus’s time. For example, Aslan voices what he maintains is the scholarly consensus—the notes in which he combs over his sources are nearly as rewarding as the main text—when he asserts that “Illiteracy rates in first-century Palestine were staggeringly high, particularly for the poor. It is estimated that nearly 97 percent of the Jewish peasantry could neither read nor write . . . ”

However startling this may be for those who think of Jews as eternally the people of the book, it does help explain the strange fact that there is no written testimony from the rebels themselves about the Jewish Revolt in which they fought and died. What we know from contemporary sources comes in large part from Josephus, a Jew, yes, but one who had gone over to the Roman side and wrote in Latin.

Aslan’s easy command of detail gives this book peculiar resonance beyond the core story of Rome, Jews, Christians, and Jesus, as if that story were not resonant enough. For example, the Jews who committed suicide at Masada, rather than surrender to Rome after Jerusalem had fallen, had printed coins labeled, in Hebrew, “Year One.” Year one was how French revolutionaries characterized the end of the monarchy and the beginning of the Republic.

Another example is “No lord but God!,” the slogan of the Sicarii, fierce Jewish assassins who targeted Jews they thought in league with Rome or the Hellenized elite. If that slogan reminds one of “There is no God but Allah,” perhaps this is one place where Aslan invites readers to grasp that the history he writes about has some connection with the Islamism from which his family fled. But that is only speculation.

Put simply, Zealot is a passionate and powerful book. I am a secular Jew who can’t but welcome its conclusion that Christianity pulled a role reversal on Jesus and made this failed revolutionary Jew into someone who eschewed his people and its traditions in favor of Roman power. But Jewish or not, I would welcome this book for its account of the epochal events that took place in first century Judea.

Harvey Blume is an author — Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo — who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in the NY Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. My blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.