Theater Review: “Valentine Trilogy” Has a Lot of Passion but Could Use More Smarts

So what’s a hero to do but throw punches and kicks in the name of love and forgiveness?

The Valentine Trilogy by Nathan Allen. Directed by Skylar Fox. Presented by The Circuit Theatre Company. At the Roberts Studio Theatre at the Boston Center for the Arts, through August 17.

By Ian Thal

The House Theatre Company of Chicago is one of the darlings of the Second City’s theater scene. Currently in its 11th season, it has already been the subject of at least one doctoral thesis. One of its early popular successes was the genre-spanning The Valentine Trilogy, written by and starring playwright, songwriter, actor and House Theatre artistic director Nathan Allen. Produced between 2004 and 2006 over the company’s first three seasons, the epic project explores the permutations of the concept of the hero.

San Valentino and the Melancholy Kid starts off as a traditional western: Elliot Dodge, better known as The Melancholy Kid (Ryan Vona), is a naïve, young horse-thief on a quest to avenge the death of his father. Knowing only that his father was gunned down in the fictional town of San Valentino, he joins up with a team of five cowboys herding cattle in that direction. With the exception of a a jovial Russian emigre nicknamed “Cubby,” who serves as the cook, each cowboy has a dark secret that demands he flee his prior life. The guys take turns mentoring the Kid, especially Captain Hank Shepherd (Jared Bellot), a former preacher and former Confederate officer, and his alcoholic sidekick Ollie Pendergast (Justin Phillips), the only other survivor of Shepherd’s company. The latter reportedly sold his soul to the devil for a six-shooter that can’t miss. The men initiate The Kid through a series of rites: the mysteries of the universe as seen in the twirling of a lasso, his first sexual experience in a brothel, and cowboy philosophizing about the forces that every hero must confront—love and violence, sin and forgiveness.

Given that Allen concentrates on the hero archetype, it should be no surprise that the influential Jungian mythology scholar Joseph Campbell is clearly evident (the aforementioned doctoral dissertation examines the production history of House Theatre’s first six years via Campbell’s archetype) but so is Freud. The Kid has an almost child-like admiration for the father he has set out to avenge, even though that father was frequently absent during his childhood (he rode the Pony Express and presumingly also fought in the Civil War). But like Hamlet, and even more so like Oedipus, The Kid must discover not only his father’s killer but the alarming truth of who his father is.

The Oedipal myth demands that The Kid’s father’s fate be tied in with the sins that have sent his new companions wandering. Likewise, when he is sent on his first rite of passage as a cowboy, to capture and brand a cow who has strayed from the herd, she becomes a vessel through which his mother’s ghost speaks to him. He names the cow after her, and the subsequent branding is staged to resemble a sexual assault. The play’s forays into magical realism suggests that beyond psychological conflict lies a cosmic struggle between good and evil—this apocalyptic conflict assumes centrality in the subsequent plays in the trilogy.

The second play, The Curse of the Crying Heart is a samurai epic or chambara about a masked samurai known as Sorrow (Vona, again), armed with a sword forged in Hell, who is assigned as the body guard for Princess Sakuroko (Madeline Wolf Shulman) on the eve of her marriage to the honorable feudal Lord Goroda (Graham Techler). She has only recently emerged from hiding after her family has been assassinated at the order of the rival Lord Zatsumoro (Philips), who is in league with the demon Obakekuro, the Black Ghost (Simon Henriques). As customary with the genre, the central conflict is between that of ninjo (one’s emotional authenticity or conscience) and giri (obligation to one’s clan, lord, or position). Warrior Sorrow and the princess are in love, but she must marry Goroda in order to unify Japan under a legitimate regime.

The third installment, Valentine Victorious!, is a superhero-noir of the sort that became popular with the success of Frank Miller’s 1986 graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns and Tim Burton’s 1989 film Batman. Elliot Dodge, still masked and clad in black, has become a vigilante named Valentine with a metal heart-shaped shield on his chest. The story begins in medias res (an echo of the closing scenes of Curse of the Crying Heart) with Valentine winning his city a temporary reprieve from destruction but accidentally causing the death of Angela, a socialite, during her wedding to George Reed (Techler) who appears to be the last honest police lieutenant in Boston (the original production set the action in Chicago.)

Threatening the city is a trio of big bads: Julian Sabatino, a crime boss with the audacity to assassinate the mayor of a major city and the connections to escape prosecution (only slight hyperbole here, where James “Whitey” Bulger had his allies in the State House and had co-opted agents in the FBI’s Boston offices); a mutilated former cop turned—through super-science and tragedy—into a monster called “The Detroit Fist”; and a cybernetic son-of-the-Devil (or so he says) known as Black Skull.

The story makes about as much sense as the super-science that grants Valentine his nigh-invulnerability to injury. The plot pivots on Black Skull’s need for Sabatino’s money to finance the rebuilding of his demonic atomic bomb. Rebuilding is the key word here; he tried to demolish Boston once before, and he must use he original bomb’s shards. Apparently, a mundane atomic bomb made by the mere mortals of the Manhattan project is not sufficient. His plan is to blow up Boston so that he can plunge the entire world into a cycle of self-righteous revenge and send billions more souls to hell. Why? Because he’s the son of the Devil and not the mundane sort of terrorist we read about in the news.

So what’s a hero to do but throw punches and kicks in the name of love and forgiveness?

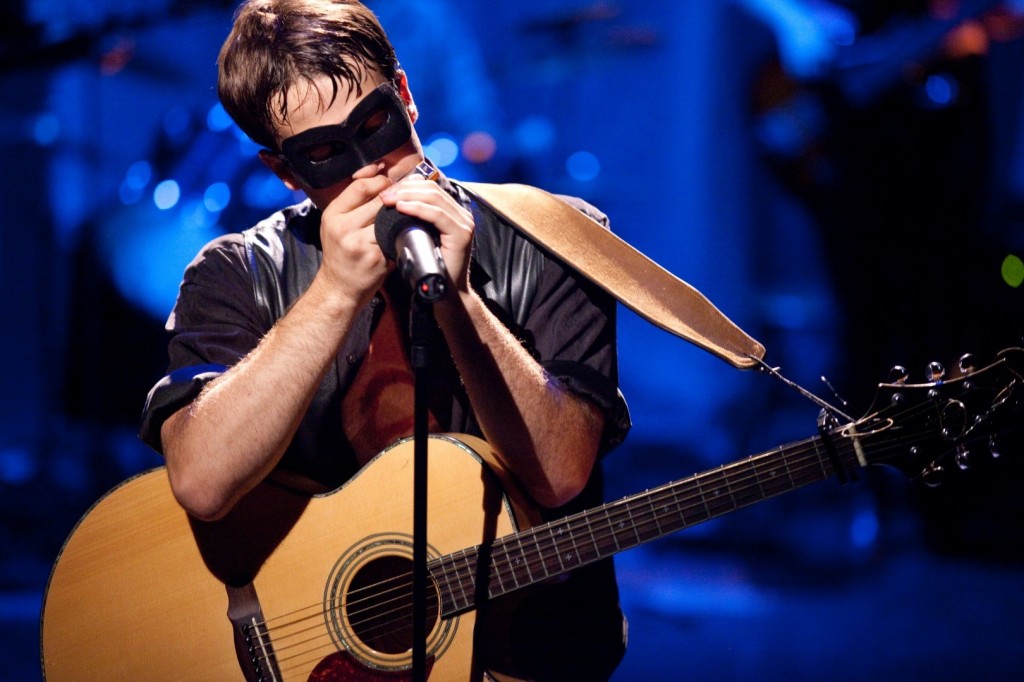

All through the cycle The Trick Hearts (the house band under the direction of celloist Linda Bard), performs songs in between scenes, usually with Vona singing lead and playing rhythm guitar. While thematically linked to the story, the tunes more often than not simply comment on the play rather than move the dramatic action forward—consequently, their inclusion seems more of an indulgence of Allen’s, who besides writing the play and the songs played the the black-clad hero when the trilogy was originally staged at The House Theatre. That said, The Trick Hearts is a quite capable band, playing rock, country, and western in San Valentino, and post-punk alternative rock (recalling the Pixies and Smashing Pumpkins) in Curse and Valentine.

The music, however, is hampered by the sound design. When amplified, Vona’s voice often distorts, and the lyrics become difficult to understand—especially unfortunate because when Vona sings un-amplified, he proves to have a rich and versatile warble that fills the room. Bard’s cello is also unnecessarily amplified to the point that, in the scenes where she plays solo, she drowns out the dialogue. Finally, in Valentine Victorius!, the musicians are all placed on different levels on a structure of risers. Because there is no monitor system, they are unable to hear one another, resulting in a muddy sound that isn’t as much of a problem when they are all on the same latitude. Such sound problems may be understandable during a one-night club date, but they are inexplicable during a three-week run.

The important question for Allen is whether this trilogy is coherent. The popular wisdom regarding sequels holds true here—knockoffs are rarely as good as the original. San Valentino and the Melancholy Kid is the strongest of the three scripts: the characters and dialogue are at their richest because, despite the cosmic struggle going on behind the scenes, the dramatic stakes are at their weightiest: the Kid’s Oedipal quest takes place amid a band of veterans and outlaws in the morally ambiguous setting of a post-Civil War United States.

The Curse of the Crying Heart‘s palace intrigue unfolds rather predictably for the genre-savvy (even if chambara stories do not typically include demons or other supernatural elements—merely human skills brought to a high level of excellence). Still, the script provides a solid framework for eye-filling theatrical spectacle, which the Circuit Theatre Company provides with pleasure. Fight choreographer Trevor Olds excels here: the clanging of metal against metal reminds audience members that the katanas on stage are real.

Valentine Victorious!, however, will prove frustrating to anyone who has become fatigued with the number of times they have heard or read a villain taunt a hero with some variant of “You and I are not so different!” Despite having similar predilections for costumes of dark hues, the superhero who seeks to save the world is a very different animal than the supervillain who seeks to destroy it. Even the superhero deconstruction sub-genre (exemplified by Alan Moore’s 1986-87 Watchmen, where the heroes are remarkably ineffective and the villain saves the world) reflects that distinction. The Valentine Trilogy, however is much too earnest in its hero worship to consider deconstruction an option.

At first glance, the three plays don’t share even a casual continuity. The relationships are mostly meta-textual: there are recurring archetypes and symbols (the Bleeding Heart brand in San Valentino becomes the Crying Heart tattoo of Curse, which morphs into the heart-shaped shield of Valentine), but scenes such as the honor battle in Curse of the Crying Heart have no place in the worlds created by the other plays.

The Trilogy shares some structural characteristics with Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion cycle of novels: his protagonists are perpetually reincarnate avatars of the same archetypical Champion, fighting and struggling across many genres of fiction. Moorcock’s champion, like Allen’s, has an often tragic love for an Eternal Consort and often fights with a powerful weapon, frequently a black sword, which, resembling the six shooter, katana, or bomb in Allen’s trilogy, has been forged in Hell. In another parallel, Moorcock is also a songwriter, and he has penned songs based on his stories for such bands as Blue Oyster Cult, Hawkwind, or his own Deep Fix (not coincidentally, also the name of the band that Moorcock’s post-modern, absurdist super spy, Jerry Cornelius, fronts in 1977’s The Condition of Muzak.) Judging by The Valentine Trilogy, Allen is neither as experimental nor as political as Moorcock.

The Circuit Theatre is a young company: a quick glance at the playbill reveals that most of the cast, crew, and production staff are still undergraduates or recent graduates, many of whom have been working together since high school. The company only produces plays during the summer break. This translates into a troupe with nerve to spare.

And every ounce of the company’s ambition is needed in the effort to pull off a project of this scale. Director Skylar Fox’s blocking is generally thoughtful, displaying a good eye for effective line-of-sight. He is often creative, as in Valentine Victorious! when he uses a prop doorway on rollers to approximate the montages created by panels on a comic book page or in a film editing room. He also taps into an impressive array of theatrical techniques, ranging from cantastorias and tableaux to puppetry and juggling. (The flying butcher knives in San Valentino‘s the beef stroganoff scene is one of many comic highlights.)

Designer Christopher Annas-Lee’s sets evoke the ramshackle, wooden structures of frontier towns and the expansive, rocky landscapes of the Wild West as well as the paper walls and the calligrapher’s brush-stroked mountains of an imaginary feudal Japan. His use of lighting in Valentine Victorious! recalls the chiaroscuro found in panels from Will Eisner’s classic The Spirit and Frank Miller’s hard-boiled Sin City comics. Corina Chase’s costuming choices in San Valentino are bold while her most colorful visions pop up in The Curse of the Crying Heart.

However, while youth fuels ambition, it also means that most of the cast has yet to develop the gravitas needed to make Allen’s frequent excursions into clichéd dialogue sound meaningful (especially in the superhero-noir Valentine Victorious!, which has more than its share) or to flesh out less sketched out characters. Despite this, there are a few achievements worth noting: Justin Philips is particularly strong in both the roles of the alcoholic gunfighter Ollie Pendergast and the flamboyantly threatening gangster Sabatino. Jared Bellot invests Captain Shepherd with a broken humanity: it is an ironic casting choice—the Confederate officer is played by an African-American actor. Madeline Wolf Shulman’s strongest acting moments seem to come when she dances, either in the love scene between Angelina, as a dancer from Tijuana, as the Melancholy Kid, or in Reed’s dream of his murdered bride. Her arabesques and turns leave her tantalizingly untouchable.

Tagged: Ian Thal, Nathan Allen, Skylar Fox, The Circuit Theatre Company