Book Review: A Remarkable “My Beloved World”

This is not just a story of a plucky girl succeeding; in weaving her complicated story and giving credit to those who helped her to understand how to think critically and how to develop her own moral philosophy, Sonia Sotomayor never forgets that luck and serendipity also play a part.

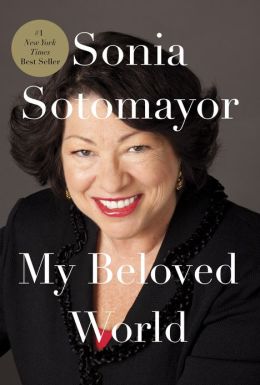

My Beloved World by Sonia Sotomayor, Knopf, 315 pages, $27.95

By Roberta Silman

One of the reasons I love to write for The Arts Fuse is that its editor, Bill Marx, often sends me worthy books that don’t get much attention elsewhere. And when I find something I really love, I feel like an explorer breaking new ground—or really more like I imagine Keats felt discovering Chapman’s Homer. How many wonderful books there are out there that few people seem to know. And how good to be able to review them.

Yet once in a very great while the book that everyone is reading and buying turns out to fulfill all your expectations. That is the case with Sonia Sotomayor’s memoir, My Beloved World, which she wrote with the help of Zara Housmand. What makes the book so remarkable is the intangible thing that makes Sotomayor so remarkable. All the ingredients of her childhood could be regarded as difficult: her parents came from Puerto Rico in the ’40s and married and settled in the south Bronx, but within a few years after Sonia’s birth in 1954, her father descended into alcoholism, her parents’ marriage fell apart, and her father died when she was nine. Her mother brought up Sonia and her younger brother Junior as a single mother while the sparkling center of the family, her father’s mother, her beloved Abuelita, faded into a permanent state of grief. And when Sonia was seven she got Juvenile diabetes (Type 1) and was forced to take full responsibility for her own care because no adult in the family would, or could.

These ingredients for disaster are laid out simply and clearly, and although you can feel her angers and hurts, you keep waiting for the axe to fall, for Sonia to say, “Poor me.” Yet there is not a trace of self-pity in any of the stories she tells about her slow realization that being born Puerto Rican in the south Bronx in the mid-50s was not exactly a recipe for great success. For, unlike many stoics, young Sonia didn’t become resigned or detached but somehow figured out how to survive without losing her sense of humor, her curiosity, or her innate dignity. Nancy Drew rescued her one summer; the Encyclopedia Britannica became the solution for another. When she realized she was not at the top of the class, Sonia asked a girl who was to give her some hints on how to study; when she was in danger of becoming bored or succumbing to the temptations of drugs or drink that surrounded her daily, she got a job; when the household became shrouded in a grief so claustrophobic she and Junior couldn’t breathe, Sonia shouted at her mother until she was heard.

This beautiful book, which seems to have rolled off the tip of her tongue, is really a testament to an attention to detail that has been a hallmark of Sotomayor’s life. Indeed, despite all the obstacles she has overcome and is still overcoming because she has a chronic illness, she maintains the most amazing optimism. By the end of the book, you are convinced, as she is, that she has been blessed. What she doesn’t seem to understand—and for that you come to love her—is that her unique combination of intelligence and determination has given rise to a story that is far more than an immigrant story, or the story of a child overcoming a handicap, or even a rags-to-riches story.

My Beloved World is fresh evidence that intellectual and social success can be kindled in places where the embers are barely burning. That there are values to be passed down, role models to look up to, and goals to be achieved if you know where to find them. But only if we can throw off our cynicism that “nothing matters,” or that “it is what it is,” or the belief that our destinies are in biology or geography or gender. In her preface, Sotomayor explains that “. . . experience has taught me that you cannot value dreams according to the odds of their coming true. Their real value is in stirring within us the will to aspire.”

One of the saddest tales is Sonia’s story of her cousin Nelson, the smartest of the extended family, who succumbed to drugs and reformed, but too late, and died in his 30s. Why Nelson and not her? There is no answer. The good news is that here she is. When she was a toddler, the family called her an aji, a hot pepper, and one of the places where I laughed out loud was her description of getting her head stuck in a bucket so she could hear how her voice sounded and having to be rescued by a fireman.

But this is not just a story of a plucky girl succeeding; in weaving her complicated story and giving credit to those who helped her to understand how to think critically and how to develop her own moral philosophy, Sotomayor never forgets that luck and serendipity also play a part; moreover, she is not afraid to admit where she didn’t measure up or was not alert to “the writing on the wall,” and somehow had to revise her expectations, as she was forced to do when her young marriage ended. Or the hard work that she had to do to accept her mother’s flaws and effect a true reconciliation with her.

Sotomayor truly believes that “there are no bystanders in this life” but instead of making her rigid, this basic belief seems to have made her uniquely suited to her profession. Although there are dozens of other quotable incidents in this book, the one that is most telling, for me, comes toward the end when Sonia remembers a girl she met at a conference of girls from Catholic schools all over New York City. She found herself sparring with this person and finally wanted to know “what had inspired the hostility that I sensed from her.”

“It’s because you can’t take a stand,” she said, looking at me with such earnest disdain that it startled me. “Everything depends on context with you. If you are always open to persuasion, how can anybody predict your position? How can they tell if you’re friend or foe? The problem with people like you is that you have no principles.”

Sonia Sotomayor — we should be grateful that she found her way through our country’s judicial system.

As Sotomayor confesses in the succeeding paragraphs,

I have spent the rest of my life grappling with her accusation. . . . There is indeed something deeply wrong with a person who lacks principles. . . . There are, likewise, . . . values that brook no compromise. . . . But I have never accepted the argument that principle is compromised by judging each situation on its own merits, with due appreciation of the idiosyncrasy of human motivation and fallibility. Concern for individuals, the imperative of treating them with dignity and respect for their ideas and needs, regardless of one’s own views—these too are surely principles and as worthy as any of being deemed inviolable.

Here her immense compassion and learning intersect, leaving us grateful that she found her way through our country’s judicial system. And as I reached the end of this terrific memoir, I found myself remembering my mother, who, like Sonia’s, was always asking, “Why do you always have your nose in a book?” and later, when I had my own family, “Why do you need all these books?” By then I was smart enough to answer, “They are my friends, and they teach me how to live.”

Sonia Sotomayor’s My Beloved World is a book for parents, and teachers, and their students. A book for everyone. Better than anything I have read in a long time, it teaches us how to live.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again; and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She writes regularly for The Arts Fuse and can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

I enjoyed Sotomayor’s memoir. I found her engaging and open to sharing her ‘Beloved World.’ Perhaps it was because she grew up in New York City, where the possibilities to realize the American Dream are present….a true diverse melting pot. Affirmative action levels the ‘legacy’ or athlethic playing fields, alllowing one to enter college through the scholar door, as well. She represents the best of America, intelligent, fair and compassionate….. a welcome addition to the Supreme Court.