Theater Review: “Bacchae” to Basics

Sometimes I wonder if Euripides saw the very texture of reality as ironic. Saw the gods in their interactions with human beings as essentially playing. A frightening idea. But at least it entails the assumption that Euripides himself was not playing. Anne Carson, in her introduction to her translation of Euripides’ “Orestes” in “An Oresteia.”

Melissa Barker, Jennifer O’Connor, and Elizabeth Rimar strike Bacchic poses in Whistler in the Dark’s production of The Bacchae.

The Bacchae by Euripides. Translated by Francis Blessington. Directed by Meg Taintor. Presented by Whistler in the Dark Theatre at the Rehearsal Hall at the Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts, through May 16.

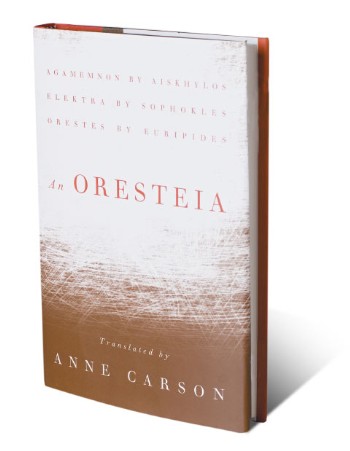

An Oresteia by Aiskhylos, Sophokles and Euripides. Translated by Anne Carson. Faber and Faber, 255 pages.

Reviewed by Bill Marx

Could it be that, as poet-scholar Anne Carson suggests, Euripides takes even the primal ironically? The thought occurred to me during Whistler in the Dark Theatre’s shouty production of “The Bacchae,” which approaches the play’s vision of Dionysian anarchy via athletic undulations and high decibel levels. Director Meg Taintor wants to evoke the tragedy’s terror, pain, and pity and at times she does – when the performers stop trying so damned hard to whoop the valleys elemental.

Most of the productions of “The Bacchae” I’ve seen over the years also strained at the libidinal leash, their campy rather than frightening pictures of the possessed women of Thebes often involving young actresses dancing, hooting, and bopping around with arty abandon.

Carson suggests that Euripides may be putting more spin on the “darkness” than we think. And, as perverse as it sounds, it may be fruitful for stage companies to bring a somewhat lighter touch to the classic’s amoral furies. “The Bacchae” is not just about how a transcendent “life-force” (in Taintor’s words) blows us away, but that Pentheus, too arrogantly rational for his own good, is unable to acknowledge the Dionysian roots of his own nature. Reason, or sanity, must admit the irrational desires and concerns that drive it; that’s the only way it can prevent these yearnings from sliding into an anarchy that endangers reason itself.

“The Bacchae” is not as much about the ambiguous strength of religion, as the “Boston Globe” critic claims (“an exploration of the power and limits of religious ecstasy”), but a warning to a secular mentality gone smug. Moderation survives because of its fragile recognition of the extremes.

The irony of the production is that the small space of the Rehearsal Hall invites a more intimate approach to sound, a softer evocation of brutal energy that would be expressed though pressurized containment, nuanced modulation, rather than full throttle delivery. For today’s audiences, the volume is jacked up everywhere – in the movies, on TV, and in theater presentations mic’ed to the max. Here is an opportunity to make us lean forward, to listen to fury whispered as well as shouted. A tragedy skillfully domesticated would be an interesting experiment.

But the production’s chorus, gung-ho and large-lunged, delivers most of its lines in a see-sawy monotone that runs roughshod over the language’s emotional ups and downs. Given that the Bacchants spend days yelling at each other before and after ripping cattle apart with their bare hands, you would think their voices might become scratchy. Praise to Dionysos, strengthener of vocal cords!

The quieter moments of the production fare better; they are stiff but sturdy. Phil Crumrine could play Pentheus as less of a spoiled repressed brat from the get go – it would be refreshing to see the guy try to think his way through the challenge of the Bacchants rather than, as is oh-so-customary, betray his sexual hang-ups so quickly and transparently. The rest of the cast members – Melissa Barker, Curt Klump, Jennifer O’Connor, and Elizabeth Rimar – are hardy and earnest, but never terrifying or thrilling.

Francis Blessington’s new translation, though clear and substantial, comes off as Masterpiece Theatre-ish, too ornately quaint for my taste, slinging such stuffy phrases as “wrapped in holy fawnskin,” “glib city vagabond,” and “camouflaged in leafy shrubs.” (Blessington is a John Milton specialist and it shows.) Those looking for a more radical (and Modernist) Euripides should pick up the translations of poet-scholar Anne Carson, whose latest volume, “An Oresteia,” collects her versions of three Greek tragedies that tell the story of the doomed house of Atreus: “Agamemnon” by Aiskhylos, “Elektra” by Sophokles, and “Orestes” by Euripides. New York’s Classic Stage Company produced the scripts last month – I wanted to see the productions but I couldn’t get away.

I agree with Helen Shaw of “Time Out” that the Aiskhylos and Sophokles texts call for a more buttoned down approach than Carson gives them, but her translation of “Orestes” is a lyric corker. The poet clearly relishes Euripides’s ambiguity, his irreverence, his ornery unpleasantness (no character in the play is remotely sympathetic), and his robust sense of showmanship. In “Orestes,” Carson applies an exuberant, Bonnie and Clyde approach to the anti-hero’s final violent confrontation with the law. She is willing to take risks, to embrace linguistic registers high and low, including the vulgar, such as in a slave’s reaction to an attempt on Helen of Troy’s life:

Where I come from people say bad shit

happening

when they mean death.Another quaint barbarian idiom is real bad

shit happening—

that covers blood on the floors

and a houseful of swords.

If the directness of that approach tantalizes, move from “An Oresteia” to “Grief Lessons,” a volume (from New York Review Books) that brings together four other Carson translations of Euripides: nervy versions of “Herakles,” “Hekabe,” “Hippolytos” and “Alkestis.” In the preface to that book, the poet writes that in Euripides “some kind of learning … is always at the boiling point.” Carson has yet to translate The Bacchae” – I assume that its bubbling somewhere in the back of her mind.

Tagged: An-Oresteia, Anne-Carson, Books, Euripides, Featured, Frances-Blessington, Meg-Taintor, Persona Non Grata, The-Bacchae, Theater, Whistler-in-the-Dark-theater