Theater Review: Superb American Bunraku

. . . these plays in their various modes approach the theater as a means of knowing and not merely as a means of expression. — Richard Gilman, “The Drama is Coming Now.”

Disfarmer conceived, directed, and designed by Dan Hurlin. Original music by Dan Moses Scheier. Text by Sally Oswald. Part of the Emerging America Festival at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA, May 15.

Disfarmer: The Portrait of an Artist as a Puppet

Reviewed by Bill Marx

Dan Hurlin’s impressionistic puppet show, Disfarmer, is a mesmerizing meditation on the sad but oddly inspiring life of portrait photographer Mike Disfarmer (1884-1959), the ultimate American outsider artist. This is a beautiful production, at its paradoxical best combining alienated poignancy and striking visual poetry. It also invites you to think: Hurlin uses the theater as a means to dramatize a peculiar way of knowing the world and the self. No doubt this will be one of the most imaginative shows of the Boston season—those interested in the art of the theater take note.

Do not go tonight (the last performance in Boston, alas) expecting, like some misbegotten critics, a cute bio-drama, a folksy homage to small town Arkansas, where Disfarmer plied his trade as a photographer for decades. Instead, Hurlin supplies a disjointed tale of Disfarmer’s Last Tape, a melancholy though often witty examination of the isolated existence of a mentally disturbed man who didn’t know he was an artist.

His birth name was Mike Meyer, but the photographer changed his moniker to Disfarmer (no-farmer) after his studio in Heber Springs, Arkansas was destroyed by a tornado in the 1920s; the renaming was an act of radical estrangement from his family and from others — his principle interaction with people, at least in the show, is through the acidly searching lens of his camera. He was an inveterate beer drinker and, at the end of his life, subsisted only on brew and chocolate ice cream.

Hurlin and company suggest Disfarmer’s inner life through the agile use of Bunraku puppet techniques (the Disfarmer mannequin comes in six sizes), wry use of miniatures to suggest everything from a tornado to a general store, and a voice-over narrative (delivered in Mr. Rogers-ish style by Hurlin) that evokes the gruff, lonely eccentricity of Disfarmer’s personality.

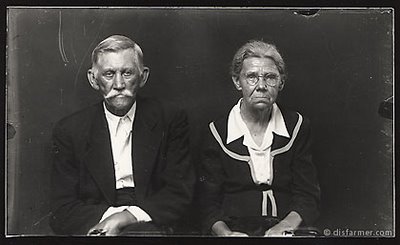

A portrait taken by Mike Disfarmer

Disfarmer explores a life lived in a monochromatic dream world, dramatizing the frightening psychological territory where creativity dovetails with fetish, a place where each morning Disfarmer measures his feet to see if they have grown overnight.

There are occasional moments of fussy preciousness in the production, but Disfarmer‘s weirdly heroic vision of a functioning dysfunctional artist, buoyed by its nimble use of striking images and sliced-and-diced, bluegrassy music score to communicate unconscious truths, creates an indelible stage picture of a strange picture-taker.