Short Fuse Film Review: Dissident Artist Ai Weiwei — The Anti-Mao

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei speaks for an alternate China, another possibility for it. In a sense, he is the anti-Mao.

Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry. A documentary directed by Alison Klayman. At selected New England cinemas.

By Harvey Blume.

This fine documentary opens with shots of the many cats with whom Ai Weiwei, China’s best-known artist/activist, shares his Beijing studio. One feline has learned to open a door by leaping up to release the lever, after which it saunters out. Ai Weiwei observes that having opened the door, the cat never returns to close it.

Point nicely taken about activism and art.

This is followed by an orange tabby getting willfully tangled up in a small, wood model Ai Weiwei is assembling. He opines that the cat won’t destroy it. He’s completely mistaken and chuckles when kitty does.

Point taken about playfulness.

But it would be a mistake to think of Ai Weiwei, now in his late fifties, as altogether kittenish. As the film documents, it is often fury that drives him. That fury is on display when he goes back to Chengdu where a beating by police in 2008 caused severe headaches later traced to a subdural hemotoma or bleeding into the brain. With director Alison Klayman filming the encounter, he flies at one of the cops, tearing the man’s sunglasses off so he could be plainly identified. Laying hands on a cop is dangerous anywhere, and having a camera around is no guarantee of safety. Ai Weiwei’s anger propels him, and a sense of duty. When asked, at one point, why he seems so fearless, he responds haltingly that, on the contrary, he’s quite fearful but has concluded that “If you don’t act, the dangers become stronger.”

As a rule, he acts. But even he can be daunted, at least temporarily. In April 2011, he was arrested in Beijing and kept under 24-hour guard at an undisclosed location; he had, effectively, been disappeared. When released 81 days later, he was thinner and uncharacteristically reticent, refusing to talk about the experience. But not for long: a few weeks later, he was back in full force on Twitter, which, now that his blog is banned, is the social medium through which he connects with a large Chinese following.

Ai Weiwei is one of the high profile artists Chinese authorities toy with, bestowing freedoms then withdrawing them. Arbitrariness seems to be the name of the game. The lesson is not so much about this law or that limit, ill-defined as they are and are likely meant to be. It is about authority itself—its tripwires, minefields, and irritability.

Ai Weiwei was celebrated for his role in designing the celebrated Bird’s Nest stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics but soon after denounced the games as a “pretend smile.” He told The New York Times that “What counts are the tens of thousands of lives ruined because of poor construction of schools in Sichuan, because of blood sellers in Henan, because of industrial accidents in Guangdong and because of the death penalty. These are the figures that really tell the tale of our era.”

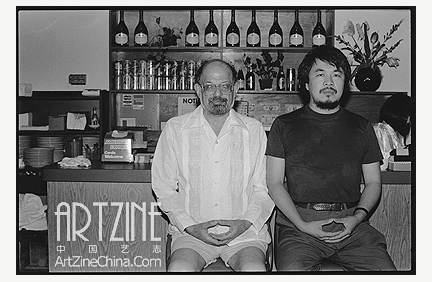

He had earlier spent a decade (1983–1993) in New York City, remarking that its lights, as his plane set down, looked to him “like a basket of jewelry.” A touch of New York at once nullified “twenty years of [state] education.” There he assimilated Western art and culture, with an accent on Duchamp and Warhol, took and exhibited thousands of photographs, and joined in protests and demonstrations. The film darts a bit too quickly past a suggestive photo of Ai Weiwei, China’s dissident to be, sitting alongside Allen Ginsberg, who might be termed America’s dissident laureate, were that not an oxymoron. As it happens, Ginsberg, who seems to have known everyone, had met Ai Qing, Ai Weiwei’s, father, on a trip to China.

Ai Qing had been one of China’s best known poets. Though he sided with the Communist Party and had penned earnest praise songs to Chairman Mao (probably not his best work), he spent much of Communist rule having rocks hurled at him, ink poured on him, for the sin of literature, while cleaning rural toilets and almost starving. Ai Weiwei, growing up, witnessed these humiliations. When Ai Qing was officially “exonerated” in 1978 and his sentencing labeled a “mistake,” his response, as per Ai Weiwei, was, “For you it was a mistake, one word, for me it was 20 years.”

Ai Weiwei had gone to Sichuan in 2008 to document the effects of the earthquake, during which 70,000 people died, including thousands of schoolchildren whose schools caved in on them because of notoriously shoddy—”tofu”—construction. Ai Weiwei used thousands of multi-colored, children’s backpacks to spell out in Chinese characters what one mother said about her daughter: “She had been happy living in this world for 7 years.”

This artist’s work and his role are not fully translatable into Western categories. There is no one quite like him here. The Chinese, of course, are numerous, and numbers therefore play an appropriate part in his work, as in the number of backpacks he used for his show about the earthquake. When he returned to Chengdu, he ordered a feast for sympathizers—there is no lack of food in this movie—consisting of thousands of river crabs. Weiwei himself was not permitted to attend this mass dinner but his friends ate very well.

Ai Weiwei speaks for an alternate China, another possibility for it. In a sense, he is the anti-Mao. Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry is an essential introduction to his work to date.

Looking forward to seeing this. Did you see the installation of the backpack work when it was at Harvard? Very moving.

i did not see the backpack work at harvard. my loss . . .

It is interesting to wonder if any American or European artist could possibly have the same scope and social impact. Ai Weiwi takes great risks, but he also has the potential to change his society in profound ways. He is no mere gadfly heckling the establishment from the sidelines, he is a real player making important moves. (Recall that he does mention chess briefly.) Can the same be said of any artist in our own world?

> Can the same be said of any artist in our own world?

no. closest comparisons may be to the likes of shakarov and havel. it’s ironic that tyranny makes art more powerful.