Book Review: Classic Supernatural Satire — “The Wild Ass’s Skin”

Helen Constantine’s new translation of Balzac’s The Wild Ass’s Skin serves this wonderful and weird book well. It is one of the great, black comic fables in world literature, an exhilarating exploration of mankind’s lack of imagination.

The Wild Ass’s Skin by Honoré de Balzac. Translated from the French by Helen Constantine. Introduction and Notes by Patrick Coleman. Oxford University Press, 288 pages, $14.95.

Sometimes literary geniuses pack more literary entertainment into what appear to be their off-speed larks than they do in their slam-dunk masterpieces. Particularly the nineteenth-century, French giant Honoré de Balzac. Yes, he’s earned his classic status for the meticulous realism of his gargantuan project The Human Comedy, which includes such achievements as Old Goriot, Eugenie Grandet, Lost Illusions, and A Harlot High and Low. But there’s nothing like Balzac when he plays hooky. My personal favorites among the Balzacian treasure trove tend to be those that gleam with a fantastical, semi-tawdry shine—there are a half dozen of his lesser known books that I devoured with delirious delight.

For decades I thought I was one of the lucky few who appreciated 1842’s The Black Sheep in Donald Adamson’s 1976 translation, a re-juggling of Cain and Abel by way of a storm-tossed melodrama that keeps up its see-saw of revenge and skulduggery until the final pages. But the secret is out: the volume pops up as number 12 on the Guardian‘s list of the 100 greatest novels of all time.

Thirty years ago, I discovered another of my epiphanic Balzacs, the most perversely compelling of them all, The Fatal Skin in a 1963 translation by Atwood H. Townsend. I still have the Signet paperback edition, the date of when I finished the book scrawled on the inside cover. So when I learned that Oxford University Press was publishing a new translation of the novel, the first in 35 years, under the title The Wild Ass’s Skin, I approached with an eagerness shadowed by flickers of wariness. Would this Faustian fantasia of excess retain for me the mind-blowing zing of decades ago? Would I, older and more disgruntled, be disappointed with what had once captivated me as a hell of a fictional ride?

I can report with relief that Helen Constantine’s translation serves this wonderful and weird book well and that—though it tries the patience with a few more patches of overwriting than I remember—it is one of the great, black comic fables in literature, a dazzlingly demented exploration of a mankind’s lack of imagination.

In 1831 when Balzac published The Wild Ass’s Skin, he was an author desperately in search of success. He had just attempted the Walter Scott historical novel formula in 1829’s The Chouans, but his revamped and reinvented approach to a popular genre hadn’t sold. So he cast about for a supernatural story that would not only catch, but in a diabolical way critique, the reading public’s jaded taste. (“The whole literature of a moribund society is mockery,” he writes in the Preface to the First Edition of the novel, which is included in the Oxford Edition.) The Wild Ass’s Skin hit a nerve—it was a commercial winner. When he went on to erect The Human Comedy, Balzac included The Wild Ass’s Skin within its gigantic framework, revising episodes so that characters that appear in his later novels, such as Taillefer, show up for cameos.

But the novel is more than a winning sales maneuver. Given the story’s exuberance and invention, its fairy-tale obsession with the mechanics of desire, I would suggest that The Wild Ass’s Skin lies at the center of the creative Big Bang that is Balzac—this yarn about possessing absolute power (and then having to figure out what to do with it once you get it) reflects the ambitions of a writer who believed his imagination was expansive enough to both capture French society and hammer out its myriad meanings. Yet the book’s vision is propelled by the necessity of restraint, a clash between explosion and implosion, hubris and repression.

Raphael de Valentin comes from fallen aristocratic stock, a penniless would-be author struggling to complete a grand philosophical work about the will while courting a beautiful, wealthy woman who is superficiality incarnate. Things go terribly wrong, and Raphael heads off to the Seine to kill himself. Before throwing himself into the drink, he stumbles into a giant antique store (think of every episode of Antiques Roadshow packed into one building), owned by a shriveled centenarian who has swapped experiencing life for the disinterested thrill of owning it in the form of objects.

Seeing that Raphael is suicidal, the shopkeeper offers him an enchanted animal skin from the days of King Solomon—the shagreen will grant its owner any wish, but once that desire becomes a reality, the miraculous leather shrinks, as does the lifetime of its owner. The more you want, the sooner you die. Dreaming of having Paris at his feet, Raphael accepts the set-up and takes the skin. He gives himself enormous wealth and a title and is pursued by an innocent, virtuous beauty who fell in love with him when he was poor. Yet Raphael becomes increasingly isolated, fighting to protect himself from his appetites as well as the desires of others. Every wish brings him closer to death. (Prophetically, like the novel’s protagonist, Balzac paid a price for wanting to devour life while living it to the full.)

As if this fantastical premise wasn’t enough to keep the reader wide-eyed, Balzac surrounds the tormented Raphael with lots of zesty earthly decadence: there’s a party filled with the fast-talking, amoral, vituperative men-on-the-make (mostly wanna-be artists and journalists) that Balzac excels at portraying as well as loose-living women who issue invitations to orgies, visits to gambling dens chock-a-block with souls-of-the-damned, and ventures into the precincts of science, where Raphael begs renowned chemists and physicists to come up with ways to stretch the skin. As Patrick Coleman points out in his informative introduction, what was striking about the book when it was published is that Balzac did not set his fairy tale back in time, as was customary, but plunks it in contemporary Paris, a city then in political and cultural turmoil. Balzac clearly relishes the ironic short circuiting: it gives him the freedom to intertwine the mundane and the mythic.

As for the new translation, it strives to be closer to Balzac’s original than Townsend’s version, which is streamlined for efficiency’s sake, telling the story as directly as possible, taking no nonsense editorial steps when the writer is not cooperative, which is often. (In her Translator’s Note, Constantine talks about how the book’s sentences are “as resistant to kneading and manipulating—stretching, bending, elongating, or compressing—as the notorious shagreen itself.”) Here are passages from the translations where the old man in the shop philosophizes to Raphael about the power of the enchanted skin:

“This,” he said, raising his voice as he pointed toward the shagreen,”is desire and ability conjoined. Here are your ideas of society, your excessive desires, your intemperance, the joys that kill, your griefs that make you live too intensely; for evil is perhaps nothing but violent pleasure. Who can determine the point where delight becomes an evil or evil a delight? Are not the brightest lights of the ideal world easy on the eye, whereas the softest shadows of the physical world always hurt them? Without knowledge no wisdom, would you not agree? And what is madness unless it is an excess of desire or power to act?”

“Yes yes! I want to live to excess,” said the stranger, seizing the shagreen.

(Constantine)

“This thing,” he said in a piercing voice, pointing to the shagreen skin, “is Power and Will combined. There lie your concepts of social relationship, your excesses of desire, your intemperance, the pleasures that kill you, the pains that make you feel too much alive, for even pain is a kind of sharp pleasure. Who can determine the point at which sensuality becomes painful, or at which pain becomes a sensual delight? The most dazzling illuminations of the world of the mind touch one’s sight gently, while even the softest shadows of the world of reality never fail to wound it. Doesn’t wisdom come from Knowledge? And what is Madness but Will and Power run wild?”

“All right, then, I’ll say yes,” the young stranger said, reaching out for the shagreen skin. “That’s what I want—to live to excess.”

(Townsend)

Constantine’s version is the more dramatic of the two: it serves up more questions, introduces the notion of pleasure and evil, and has Raphael grabbing the skin. Townsend’s approach is neater, though it muddies the waters with the introduction of “Power and Will.” Here the shopkeeper sounds a bit preachy, handing out answers rather than inviting Raphael to come up with his self-damning responses to the skin’s temptations.

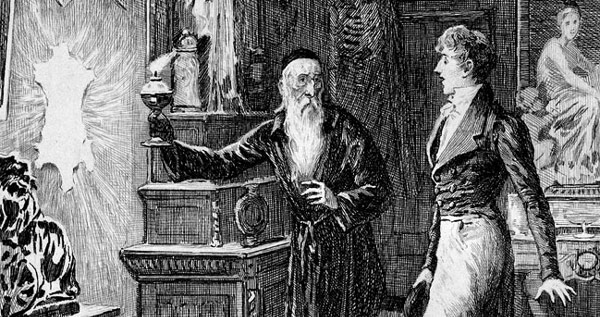

Detail from an illustration on the title page of an early edition of Honoré de Balzac’s novel “The Wild Ass’s Skin.” (La Peau de Chagrin).

Overall, Townsend chops up Balzac’s long paragraphs into manageable pieces, smooths out the convoluted syntax, and removes arcane references. His is the more efficient read, but the OUP version, with its dozens of notes and awkward hunks of prose, is closer to the unruly source. Balzac’s historical and literary references offer important clues to the book’s rich vision: repeated allusions to Rabelais’s Gargantua, such as Carymary, Carymary, are tip-offs to the kind of lethal farce Balzac has in mind.

Many critics see The Wild Ass’s Skin as containing a moral reprimand: indulgence has its depleting price—it burns up time. Townsend’s translation leans in that direction. If only Raphael had been up-right enough to refuse the skin or to decide to do good with it, thus sacrificing himself for a better world. For Coleman, the book’s tit for tat — – live large and deplete your life — is relevant today via the crisis of climate change. The more we take now, the less future we will have. And there is that kind of warning relevance in the book.

But Balzac is not serving up a civics lesson but a diabolical celebration of imaginative excess. As Coleman suggests in his introduction, nothing stops Raphael from wishing for more wishes, for asking that the skin grow bigger after each task is done. Raphael is the perfect representative of a society in which the fear of death shrinks the possibilities of desire (all mockery and no creativity), and part of Balzac’s satiric intent is to point out that limiting connection. Challenged to a duel, Raphael doesn’t wish it away, but turns his miraculous feat of sharpshooting (he points his gun into the air and still shoots his challenger through the heart) into a mockery of all things macho.

Raphael is given enormous power—and he does nothing with it, neither particularly evil or virtuous. That is part of Balzac’s delicious joke: absolute possibility does not corrupt absolutely.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: French literature, Helen Constantine, Honoré de Balzac, Oxford University Press, The Black Sheep, The Wild Ass's Skin

Stefan Zweig’s biography of Balzac, now available in eBook form, Balzac by Stefan Zweig, reads like a thriller — Balzac’s life itself was a “diabolical celebration of imaginative excess”.

Excellent review, Bill! I wonder if Oscar Wilde was a fan–sounds like it has a bit of the Dorian Gray about it.

Hi Ev,

I have no doubt that Oscar Wilde read Wild Ass’s Skin — because it set magical doings (a Faustian bargain) in a contemporary setting, the story made a considerable impact on the fables of Wilde, Stevenson, James, etc.

Balzac’s connection between living large/living less also struck an enduring chord. I don’t remember where, but Norman Mailer argued that taking drugs (LSD, etc) intensified life in such a way that it shortened your life. You lived years in a few hallucinogenic minutes.

You mention a half dozen of his lesser known novels. What specifically?

Balzac’s novels Ursule Mirouët,, Louis Lambert, Séraphîta, and Cousin Pons range memorably into the occult, though they don’t handle it with the supernatural swashbuckling of The Wild Ass’s Skin. Among the shorter pieces, “La Grande Bretèche” is a wonderful ghost story.