Book Review: Robert Walser’s Big Small Thoughts — Modest But Miraculous

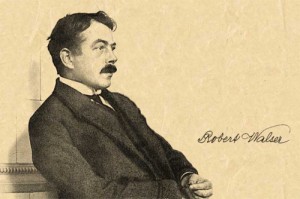

In his prose and poetry, Swiss writer Robert Walser revolts from the chaos of modernity, engaging in extreme subjectivity only to confess to the heresy that is the self, choosing to revel in the simplicity of the rural life. Not for truth but for the sake of a fleeting rapture.

By Christopher M. Ohge

Berlin Stories by Robert Walser. Edited by Jochen Greven. Translated from the German and with an introduction by Susan Bernofsky. New York Review of Books Classics, 139 pages, $14.

Thirty Poems by Robert Walser. Translated by Christopher Middleton. New Directions, 62 pages, $20.95.

The Walk by Robert Walser. Translated by Christopher Middleton and Susan Bernofsky. New Directions, 89 pages, $9.95.

Solitude dominates the artistic vision of both Robert Walser (1878–1956) and his intellectual Mitstreiter Rainer Maria Rilke. Walser’s poem eulogizing Rilke begins in a lonely château and ends with gratitude, and apparent humility:

I was content to make

beside your grave

this little speech

— (“Rilke,” 1927)

The lyric’s mix of the large and the small encapsulates the artistic charms and strengths of Walser’s fascinating variation on the arrogance of modernist individuality. Walser simultaneously sees himself as both a humble supplicant and as an apt celebrator of the greatest poet in the German language after Goethe. Diminishment becomes an act of heroic assertion.

Tellingly, the “little speech” occurs in Switzerland. Whereas Switzerland was Rilke’s final destination, for Walser it was his beginning—or begetting—and his ending. For even when Walser found himself distanced physically from Switzerland during his time in Berlin, he never wavered in his appreciation for the small. Not the insignificant, not the diminutive, but a wide-eyed embrace of detail bounded in simple, sensual pleasure.

As I approached three new, indispensable translations of Robert Walser—Berlin Stories, The Walk, and Thirty Poems—I was reminded of his marvelous novel Jakob von Gunten, in which the eponymous character, while donning his uniform in Berlin, reflects that “in this, too, I am a mystery to myself for the time being.” For Walser’s narrators, mystification is a common condition.

Walser’s Berlin was a mystery to him, because he was an outsider, and, ironically enough, the Berlin he knew is no longer identifiable. When I visited the city in 2007, I could not help but be astonished by some of the former dead-man’s-lands that now resembled Las Vegas more than a cultural capital of Europe. Perhaps no other European city has seen so many shifts of landscape, identity, instability—and Walser’s unsullied, alien eye captured those aspects (the final days of the Kaiser Wilhelm II’s regime) as they were in motion, just before Berlin began a long slog toward destruction and regeneration.

In “The Genius of Robert Walser” (New York Review of Books, 2000), J. M. Coetzee writes about Walser’s juxtapositions of the refined and the trite as well as his complicated class-consciousness:

Berlin offered him a clear chance to escape his social origins, to defect, as his brother had done, to the déclassé cosmopolitan intelligentsia. He refused that offer, choosing instead to return to the embrace of provincial Switzerland.

Coetzee’s perceptive tribute suggests that Walser’s gift parallels that of George Orwell, who wrote as energetically in defending the man on the street as he did when lampooning those in power. Orwell’s genius came not from a particularly unique stylistic brilliance; rather, his genius was for foresight, being on the right side of history, and for his visceral connection to the concerns of the voiceless. The same is true for Walser: his rustic upbringing in Switzerland encouraged his vision of Berlin to be impartial, at times skeptical, of the city’s gains and losses. Something ominous lurks beneath Walser’s satires and observations in Berlin Stories, a darkness that flickers from time to time in his descriptions of the theater houses, beer halls, galleries, cabarets, and cafés. Yet, as German critic Walter Benjamin suggested, the people in Walser’s prose can just as easily be considered fairy tale figures ensconced in the brutally real.

The Berlin Stories are compiled from Walser’s feuilletons, the literary sketches he wrote for newspapers before and after he left Berlin in 1913 for Switzerland as, in his own words, “a ridiculed and unsuccessful author.” Despite his eventual self-imposed failure, his aphoristic style in Berlin Stories is filled with vigor, as in “The Park,” where the narrator asserts that “the lively is always more contemplative than what is dead and sad” and, more subtly, in “The Market,” where “what is alive is dearer to me than the immortal.” The teasing nature of some of Walser’s critiques of the Berlin theater scene are often uproarious. His nimble sense of humor gives translator Susan Bernofsky opportunities to display her talent for transmitting difficult German compound nouns and wit into English, such as in “Do You Know Meier?”:

Meier also performs music-hall ditties with a fabulous don’t-mind-if-I-do-ishness, speaking a language that is surely the most unimpeachable there is, for he lets it drop, nugger by nugger as it were, such that a person listening to him might take a notion to kneel at the man’s feet to gather up the morsels. The tone of his voice—I’ve studied it in considerable depth—reproduces in sound the approximate impression made on the eye by the progress of a snail, so resplendently languorous, so lazy, so brown, so very reptant, so slimy, so gluey and so terribly if-not-today-why-not-tomorrow.

Bernofsky—who is currently at work on a biography of Walser as a fellow at CUNY’s Leon Levy Center for Biography—also provides a great service to readers of modernist fiction with her revision of Christopher Middleton’s translation of The Walk, a novella that shows how walking is the necessary prerequisite to writing. Along the walk, the narrator spills out his thoughts to readers while he ambles about and visits people on his to-do list—a jaunt that turns into a series of absurd soliloquies on subjects ranging from the nature of beauty to a properly tailored suit. One such enjoyable encounter occurs between the walker and a tax collector; the former is trying to negotiate a reduced tax rate because “I enjoy, as a poor writer or hommes de lettres, a very dubious income.” The tax-man doubts this contention because the speaker is always seen about town walking, to which the narrator exclaims in an elevated tone:

Walk . . . I definitely must, to invigorate myself and to maintain contact with the living world, without perceiving which I could neither write the half of one more single word, nor produce a poem in verse or prose. Without walking, I would be dead, and would have long since been forced to abandon my profession, which I love passionately. Also, without walking and gathering reports, I would not be able to render the tiniest report, nor produce an essay, let alone a story. Without walking, I would be able to collect neither observations nor studies. Such a clever, enlightened man as you will understand this at once.

But before the tax-man can respond, the walker justifies his previous comments with 10 more paragraphs on the value of walking, to which the official finally retorts, “Good!” (then, after a pause, that the application for lower taxes will be considered, and so on). The further the narrator goes out of town, the further he turns inward (probably because no one is listening). He hints that he may be imagining his dialogues (we are in the land of the unreliable narrator), and his resentment toward those who do not imbibe in “the spirit of inwardness and the enchantment of meditative life” leaves him feeling alone, misunderstood, and nauseous.

As I observed earth and air and sky, a melancholy overwhelming thought seized hold of me that forced me to say to myself that I was a poor prisoner between heaven and earth, that we all were miserably locked up in such a way, that for all of us there was nowhere a path into the other world save the one path that led down into the pit, into the earth, into the grave.

So then this rich life, all beautiful, bright colors, this joy in life, and all human meaning, friendship, family, and beloved, the tender air full of gay, delightful thoughts, houses of fathers, houses of mothers, and dear gentle roads, moon and high sun, and the eyes and hearts of men must one day fade away and die.

The novella culminates with a stoic revelation of his isolation, but do not be seduced: this line of thought follows the walker’s reading a long placard (likely a figment of his imagination) for a club that only allows the kind of gentleman “who is just simply the far better than the other ordinary people.” His realization of his eccentricity and snobbishness brings him back to earth—the rustic earth, in fact—where he is alone, aware of his insignificance, and compassionate toward his plight and the predicament of others.

Yet Middleton reminds his readers that Walser spent more time writing poetry than anything else, and the poems are the last pieces he wrote before his creative well dried up in 1932, 24 years before his death. Walser’s poetic accomplishments (and Middleton’s accomplishment of editing and translating Walser’s infamously difficult “microscripts”) in Thirty Poems show that his poems warrant serious attention, as is evident in “Börne said Heine had no character,” which acknowledges his gratitude toward his fellow sufferer, Heine, and the developing empathy (or justification of failure, depending on one’s view) that was initiated at the end of The Walk:

. . . These days

there is much talk about a European

triumphing at the current Book Fair, but

who displayed, while still alive,

a medley of strength and frailty and of shoes

he had himself to mend with cotton thread.

Compassion and, for human beings, love

are what his genius consisted of.

Who, or what was his object of affection? Walser’s acceptance of human frailty led to his love for tactile experience. The working class sympathies of this autodidact stands as a contrast to many of his erudite poetic peers whose grandiosity distanced themselves from everyday life. In “White Linen,” he fantasizes about “a little movement” that stirs the linen, which is a metaphor for his contradictory nature: half light, half dark, part resigned, part wild. Yet the metaphor falls apart once he realizes that “quiet night / has become entirely sovereign.” The music of nature amounts to his greatest love in “Chopin,” in which “bright and dark / blend in delicious melodies, / where sorrow’s beautiful, despondency / glorious.” The poems reflect Walser’s modest but miraculous resignation, his last testament to himself as a flyblown hero.

Whereas he displays brusque playfulness toward others in his feuilletons and turns inward while moving from city to country in The Walk, his poems are a unique version of the modernist pastoral—a style that revolts from the chaos of modernity, engaging in extreme subjectivity only to slyly confess to the heresy that is the self, choosing to revel in the simplicity of the rural life. Not for truth, but for the sake of a fleeting rapture.

Tagged: Berlin Stories, Robert-Walser, Susan-Bernofsky, Swiss, The Walk, fiction-in-translation, german