Dance Review: Boston Ballet Ends 48th Season on an Encouraging Note

To his credit, Boston Ballet’s artistic director Mikko Nissinen is looking far and wide for ways to expand the company’s repertory.

Fancy Free (Fancy Free, Barber Violin Concerto, Études). Presented by the Boston Ballet at The Boston Opera House, through May 20.

By Iris Fanger

A critical overview is called for, given that the Boston Ballet is not only wrapping up its 48th season but gearing up for its 50th anniversary. (Plans are already in the works: the May program featured an ad “Calling all Boston Ballet Alumni.”) With these May performances, Mikko Nissinen finishes his 10th year as artistic director, having followed founder and first director, E. Virginia Williams, Violet Verdy, Bruce Wells (interim director for one year), Bruce Marks, and Anna-Marie Holmes.

So what has Nissinen wrought? Looking at the final program, Barber Violin Concerto (Peter Martins, Samuel Barber) 1988, Fancy Free (Jerome Robbins, Leonard Bernstein) 1944, and Études (Harald Lander, Carl Czerny) 1948, some observations can be made, especially keeping the earlier programs of the season in mind.

Few companies outside of New York City Ballet stage works by Martins, the successor to George Balanchine as director of the New York City Ballet. At the May 10th program opening, the Barber/Martins proved to be a lopsided work about interlacing couples. It was performed in perfect classical manner: Lia Cirio, the ballerina in pointe shoes, was partnered with Pavel Gurevich; they were contrasted with a second duo, the bare-chested Yury Yanowsky and corps member Sylvia Deaton—both barefooted—dancing in a freer, more contemporary mode.

Of course, the couples change partners, so Cirio can behave like a Greek maenad, her hair swiveling down her back when she submits to ecstatic grabs and lifts by Yanowsky, followed by the perky Deaton, careening around Gurevich, the latter never losing the upright carriage and stiff back of the classical dancer. Deaton moves like a yappy little dog, eager to annoy her master. In concept, the theme is not new, but the performances by the women, especially the discovery of corps member Deaton, might have elevated the ballet to a keeper if it hadn’t ended so abruptly and ambiguously. Do the dancers return to their original partners or no?

The addition of Fancy Free to the Boston Ballet’s repertory is long overdue, especially given that so few of Robbins’s works have made it here. Robbins’s first ballet, created for Ballet Theatre while he was still a dancer with the company and before he defected to New York City Ballet, follows the adventures of a trio of sailors on shore leave for a night in New York City. Choreographed and premiered in New York during World War II, with a score by the unknown composer Leonard Bernstein, it was an instant success.

The curtain rises on an Edward Hopper-like image of a diner, designed by Oliver Smith. The three sailors enter in cartwheel, viewed through the windows of the shop, and then burst onto the stage amid a jazz-infused cacophony of joy. They are out for adventure and on the look-out for girls. Two women enter, one at a time, a smart plot gimmick by Robbins that sets up the later, Keystone-Cops-like competition among the men. The work has remained a staple of both American Ballet Theatre and New York City Ballet where it has served as a rite of passage for generations of male dancers.

On opening night, the Boston Ballet fielded Isaac Akiba, Paul Craig, and James Whiteside in the leading roles. They each had endearing moments, but crispness in the dancing was missing, especially when it came to creating sharp comic outlines, evoking wide-eyed innocence at being loose in the Big Apple, and pumping up pretend macho-fervor. There were some wonderful moments, such as a vignette when the sailors stuffed chewing gum into their mouths and then flicked away the balled-up wrappers in mock contest and Whiteside’s hip-swiveling backside in the Robbins’s solo to a thumping rhumba beat. It was left to Erica Cornejo, as the “girl with the purse,” to get the dating strategy swagger right, parading on stage as if she had no interest in the men. In contrast to Cornejo, Kathleen Breen Combes exuded the right amount of feminine sweetness.

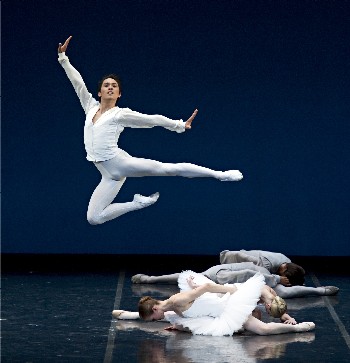

For the finale, Nissinen brought Royal Ballet dancer Thomas Lund from Denmark to teach Études to the Boston Ballet dancers. It’s a fiendishly difficult ballet to perform, for the principals as well as members of the corps de ballet. At the end, Danish ballet master Lander placed 43 dancers in view, instigating a parade of crisscrossing leaps from stage wing to wing. I remember the last time the company tried the work, perhaps while Williams was still the director. The progression of steps in a ballet class, from the barre to the sizzling, virtuosic ending, is the plot as well as the content of this piece, and it proved to be too much for the young company. Nissinen’s troupe fared better, though it did not perfectly evoke the cohesion of the corps de ballet.

Misa Kuranaga, a principal dancer, was a good choice as the opening night ballerina. She’s a former ballet competition medalist and steely in her technique. Jeffrey Cirio, aided by Paulo Arrais and Nelson Madrigal, was the most effective of the male trio that surrounded her. Kuranaga and Cirio were strong in the late April revival of Don Quixote, and their partnership should be continued. They are alike in a a number of ways—small in stature and big in confidence. Each is also blessed with a sense of humor.

To his credit, Nissinen is looking far and wide for ways to expand the company’s repertory. His biggest success in terms of finding new works has been his selection of Jorma Elo, whom he brought from Europe to work with the dancers as resident choreographer. Elo has gone on to complete many commissions here and abroad, but he returns to the Boston Ballet knowing the dancers well. Nissinen has maintained and added to the company holdings of Balanchine ballets, but he has also imported European works, chiefly by Jiri Kylian and John Neumeier, who have embraced the contemporary style of melding classical ballet steps into a range of contemporary moves. Still, the ballet staples have not been neglected. The annual production of The Nutcracker, redesigned by the highly regarded artist Robert Perdziola, will premiere next season, and a new production of Swan Lake is in the works.

A cadre of young dancers is being groomed, Akiba, Jeffrey Cirio, Deaton, and Whitney Jensen, among them, but one wishes that the Boston Ballet School was adding more of its graduates to the mix.