Judicial Review # 8: Making Sense of the “Assassins”

What is a Judicial Review? It is a fresh approach to creating a conversational, critical space about the arts and culture. This is our eighth session, a discussion about the Boston University College of Fine Arts production of the 1990 Stephen Sondheim/John Weidman musical “Assassins,” which looks at the lives and sensibilities of men and women who attempted (successfully or otherwise) to kill the President of the United States.

Assassins. Music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. Book by John Weidman. Directed by Jim Petosa. Music Direction, Matthew Stern. Choreographed by Judith Chaffee. Presented by the Boston University College of Fine Arts at the Boston University Theatre, Boston, MA, through May 10.

- Introduction by Bill Marx

- Review by Hugo Burnham

- Review by Jeff Melnick

- Artist Response by director Jim Petosa

- Summary by Bill Marx

Assassins is an unusual musical: it begins with a carnival shooting gallery in which you are invited to knock off American presidents. From there the show gathers up the men and women who have killed or tried to kill our Commander-in-Chief. Through song and dance, the culprits suggest what they had in common, what made them do it.

The motley crew range from frustrated immigrants, who shoot William McKinley and James Garfield and miss taking out FDR, to Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme and Sara Jane Moore, who attempted to kill Gerald Ford. Lee Harvey Oswald and John Wilkes Booth hover over the proceedings as guiding spirits of homeland anarchy.

Talking about assassination: A scene from the Boston University production of ASSASSINS. Photo: John Zakarsky.

After 9/11, the Sondheim & Co musical takes on some interesting resonances, particularly in its (mock?) vaudevillian treatment of violence as well as its sardonic exploration of the perverse manifestations of the American Dream of Celebrity.

For this Judicial Review the judges include Hugo Burnham, drummer and a founding member of England’s post-punk band Gang of Four, and Jeff Melnick, an associate professor of American Studies at UMass Boston, where he specializes in twentieth-century US history. Feel free to join the conversation!

Majority Opinion: The panel members at the moment—there are more responders to come—found the Boston University production to be well performed and entertaining, one calling the musical “a minor work, with real, if episodic, rewards.” The other judge was much more positive about the show. He was particularly intrigued by the relevance of its bitter yet comic treatment of ideological madness: “Perhaps it is laughter reminiscent of the way many of us look with bemusement at members of the present-day Tea Party. They are angry people decrying the very benefits of government they live off; but some of them have guns, and they have a Right, too. Don’t they?”

Minority Opinion: One judge argues that the show lacks coherence, a diffuseness propelled by the book’s conceptional problem: “It asks the audience to accept that the range of presidential assassins presented here . . . need to be respected for their distinctness as historical actors but also need to be stitched into a larger narrative about a forgotten class of people who have an important message for us.”

— Bill Marx, Editor of The Arts Fuse

Hugo Burnham

So many killers and wannabe killers . . . who knew?

Well, this Old Englander didn’t, but he was ready to be taken to school by Boston University Theatre Department’s live version of one of the “the Real History” books some of us wish we had in school. If you haven’t been to the Boston University Theatre, the inside is gently ornate, but the set for Assassins—a visual gash onstage of exposed staging and machinery from a Bruce Springsteen-meets-Duran Duran “Wild Boys” video shoot—is all techno and Stars ‘n’ Stripes. The bare lighting rig, nuts and bolts staging, and the back wall of the stage will please fans of Brecht’s “exposing the means of production” practice and made as much “. . . Sense” as a Talking Heads movie.

The band/orchestra was not hidden, not sunk into the pit where some people believe musicians belong but right in front of the audience where they could obscure the actors’ feet (and thighs for those in the front seats)—a good thing, not because lower extremities are bad onstage but because what they bring to this show is as vital as any of the acting (. . . it is Sondheim, after all). I worried about the bass fiddler’s ear getting burned by the two spotlights right behind where he stood, though. Perhaps he used sunblock.

The players were a cheery bunch with artfully paint-spattered costumes that fit their surroundings, a sort of clean dirt sartorialism. Their voices were mostly strong, especially John Scala as James Garfield’s killer, Charles Guiteau. The ensemble opened with a fairground-sounding “Everybody’s Got The Right”—yes, don’t we? And like a Beastie Boy, we should fight for it. Shades of a “Singular Sensation” came to mind as the killers lined up as if taking part in a deathly audition. But it soon became clear that the dark side of their all-American expectation of success is that if we don’t get what we want, what we believe to be our due, we can simply take it. With a gun. We can rid ourselves of whoever is denying us our right, given either by deity or our own desires, and this is what composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim and book writer John Weidman focus on as the cast weaves its way through lusty song, nutty monologues, waving of firearms, and funny scenes shared between the different killers.

Christiaan Smith-Kotlarek as John Wilkes Booth is the first up—and down—but he returns to the stage to weave in and out of the story, cajoling and tempting successive gunslingers through the ages. An imposing presence, he serves to remind us of the dark side when things onstage start to get too fun, too joyful. None of the players slouch, but some stand out, not least Leo Stagg as Samuel Byck, Richard Nixon’s would-be assassin, whose plan was to crash a plane into the White House. No subtle analogies there. And he got in a jab at Massachusetts drivers, to boot. If only he could do something about the parking around the theater, though not by waving a gun around, please. His two monologues at, rather than to, the audience were riveting and not a little unnerving. Trying to remember on which London Tube or New York City subway platform I had seen him (or somebody like him) ranting, spitting, and drinking generated some personal discomfort.

His logic was almost as convincing as his passion. Like Booth, he had a fire in his heart and he knew he was right. Il ne regrette rien. While Booth was almost devilish in his manipulation, a true Uncle Sam Devil also lurked . . . and sang and smiled and strutted. At first it seemed The Proprietor, played wickedly by Matthew Dray, would be the play’s Puck, Oberon, or cabaret MC, working each killer’s weaknesses and insecurities in the opening song. But it was Evan Gambardella’s Balladeer, a seemingly innocuous, clean-cut (and clean-costumed) boy with a guitar—an Up-With-People type of young fellow who nearly blinded the audience with his smile—who was the seam or anti-conscience running through the play. Until he swooped down to the despair of becoming, at the end, the assassin we all love to hate, the shooter (known even to young English schoolboys) Lee Oswald. (As one player asks, why do all these southern killers have three names? It gives them an undeserved gravitas, so in this review, like the rabbit, Harvey is invisible).

The scenes between the President Ford killer-hopefuls were very funny; both Melissa Carter as Sarah Jane Moore and Casey Tucker as “Squeaky” Fromme (two more different women killers you could not find—if you are even looking) are wholly believable as an annoying hippie chick and as the nutty Mom-around-the corner we all know. They are the hopeless and the obsessed, both more appealing and certainly more comical than the eye-rolling inevitability of the pratfall by Gerald Ford as he comes onstage. Cultural shorthand can be so lame sometimes.

And again, a small voice queries why we are giggling at two potential assassins. Should we really laugh at madness, at hopelessness? Perhaps it is laughter reminiscent of the way many of us look with bemusement at members of the present-day Tea Party. They are angry people decrying the very benefits of government they live off; but some of them have guns, and they have a Right, too. Don’t they? Is that a Ted Nugent t-shirt under that frock coat up there?

But each killer is played with heart and strong voice—even the whining of Harrison Brian’s “immigrant” killer Guiseppe Zangara, whose fire was in his belly rather than his heart and who missed FDR and got the Mayor of Chicago instead. (What is it about that city?) I would not want John (Hinckley) Zdrojeski to date my daughter, he was that convincingly creepy.

The staging of the final scene, the non-lethal players dropping a hail of cardboard boxes down on the ground to be carefully strewn about the stage revealing “Books” stamped on each of them gave us the “Aha . . . I know what’s coming now” moment, but it did not feel trite or forced, just inevitable and clever in a good way.

This last scene is the darkest, the most wretched. Our sunny Balladeer is now a sweating, confused, dejected weakling, and nothing is funny anymore. This is not just because his target is still so alive in our heads and hearts, but because the whole tone onstage stops just hinting at murder, stops toying with the bridge between funny and feckless. He aims and shoots . . . with the first rifle seen onstage. So many guns, so many gunshots, so many aimed at the audience, at the band (who simply didn’t deserve it), and at each other onstage. But this was sniping in a way no theater critic could match. Booth egged him on lustfully, controlling everybody onstage now, clicking his fingers at the other players to shut them up, impatient to get Lee to “. . . make a joyful noise . . .” “. . . to blow it wide open.” It was chilling.

We sat, a little afraid of when the barrel would find us, of when he would shoot. And he did. Twice.

The Ensemble then sang the hollow-sounding but forceful tune “Something Just Broke.” Not immediately, but this song becomes our song, albeit no sing-along. American or not, it all got “Broke” for everybody that day, and the songs cries it. But, no fear—the reprise of “Everybody’s Got the Right” lifts us all back into the present, into the theater where we are watching a Chorus Line of Killers, projecting strong and gustily. We can smile again, and it all ends well, nobody in the theater being Presidents, after all.

Is it all dark and depressing, or are we left confused by happy/sad songs and the humor of insanity and self-deceit? It is made clear that this skewed version of the American Dream—a lifetime of success and pats on the back—only sets us up for failure. And these killers are failures, even when their target drops. Are we supposed to feel something in common with our assassins? The attempt is there in the musical, but any emotional connection is fleeting, and we escape that conundrum with each new new song or set piece. We want to be seduced by the songs, to hum as we leave, to love it and wait eagerly for pop versions of the best songs to shoot up the pop charts. (Sorry, Billboard.) But it is Weidman’s echoing words of despair and destruction (more than Sondheim’s very wonderful songs) that are the Burr under our saddle on the ride home. (Sorry, Aaron.)

Hugo Burnham is an associate professor at The New England Institute of Art in Brookline, MA, where he has been teaching since 2000. He also teaches interdisciplinary studies and a political science class at Endicott College on the North Shore. Before academia, Hugo spent 25 years in the music business, working for record companies, in music publishing, and as an artist manager. Before such grown-up employment, he was the drummer and a founding member of England’s post-punk band Gang of Four. He lives in Gloucester, MA, with his wife Carol, a Pilates trainer-instructor and modern dance choreographer, and their 12 year-old daughter, TS.

Jeff Melnick

The thing about Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins—just finishing its run at the Boston University Theatre and featuring a fine cast of students from the College of Fine Arts at BU—is that it is just ridiculous. Not the dark-absurdist kind of ridiculous Sondheim triumphed with in Sweeney Todd or the Brecht-Weillian upset-the-applecart kind of ridiculous that he aspires to here and there in Assassins. What he achieves overall is hot-mess ridiculous: just straight-up, no he didn’t just have Squeaky Fromme and John Hinckley sing this show’s version of “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” to their respective love-objects, Charles Manson and Jodie Foster. And that song (“Unworthy of Your Love”), as Frank Rich noted in his review of the original production of Assassins in New York in the early 1990s, is one of the two best numbers in the whole show.

Since Assassins was first produced, reviewers have struggled to describe the “sweet spot” it hits, somewhere between a full book musical and a musical revue. But if there is such a sweet spot, Assassins does not get there. Don’t get me wrong, the show is consistently entertaining. But to say it lacks coherence is to suggest it has a trajectory, an argument, a position from which to speak (or sing). On the surprisingly well-populated Sondheim Lolcats site, one poster (“Sweeneytad’) remarked that there is “an unfortunate lack of Assassins jokes on here. Maybe they’re harder.” Of course the obvious answer is that the “LOL” was already built into the show, obviating the need to attach any of its lyrics to pictures of cute cats.

The central problem with the book of Assassins (by John Weidman) is that it asks the audience to accept that the range of presidential assassins presented here—and a solid half are actually “would-be” assassins—need to be respected for their distinctness as historical actors but also need to be stitched into a larger narrative about a forgotten class of people who have an important message for us. There is, literally, a vignette towards the end of the musical that has John Wilkes Booth explaining to Lee Harvey Oswald about the “attention must be paid” scene in Death of a Salesman. This is Booth’s way of encouraging Oswald to go ahead and start shooting! Assassins is at its best when it stops making the hard sell and lets the audience enjoy the brisk run through the history of American popular music. It is much harder to take seriously when it presents its motley crew of shooters as if they are extras from John Dos Passos’s USA trilogy, charged with articulating the heartbreak of his “all right we are two nations America” climax. That is a resonant message to be sure, especially in these Occupy days: it is just that this particular musical does not have the strength to carry it.

Assassins is structured around a series of meetings (Booth and Oswald, Fromme and Hinckley, Fromme and Moore, and so on) that are meant to get us thinking about the particular subjectivity of each figure and moreover to get us thinking about the historical circumstances that thrust each into the limelight. Except for Booth—who appears as an early adopter of the Confederate Lost Cause mentality—and Leon Czolgosz, killer of William McKinley and the only other shooter with a legible political position, most of the others come off as seriously mentally ill: in Assassins we meet Charles Guiteau, who seems like the slightly deranged Cousin of the Duke in Huckleberry Finn; Giuseppe Zangara, suffering from abdominal misery and shooting wildly; Sara Jane Moore and Squeaky Fromme, played as crazy hippie-chick and crazy housewife respectively; and John Hinckley, the depressed fanboy. The musical wants to find congruences between various figures and of course cannot resist bringing together the two would-be Gerald Ford assassins who discover that they share a Manson connection—Sara Jane Moore grew up in the same town as the man Squeaky Fromme came to worship. As with many of its discoveries, Assassins cannot do much more than point at this and say “Would you look at that?!”

The truth that Assassins cannot paper over is that there is no meaningful tradition of political murder in American history. There is, you would have to say, a series of lone gunmen (and women). I’m as much an agnostic about the Warren Report as the next theatergoer (remember that great line Woody Allen used to have in his stand-up act, later recycled in Annie Hall, about how he was working on a non-fiction version of the Warren Report?), but Assassins is never able to transcend its rather clunky premise in order to make any cogent political argument. The show also suffers from its decision to focus only on presidential assassins: just imagine what Sondheim could have done with Valerie Solanis, who shot Andy Warhol, and Arthur Bremer, who tried to kill George Wallace. Unlike many of the shooters sketched here, both Solanis and Bremer would have offered up fascinating writing to draw from—Solanis with her SCUM manifesto and Bremer with his chilling diary entries.

It is quite impressive how much the young people of Boston University’s School of Fine Arts were able to achieve with this material. The ingenious set imbued the show with a creepiness bordering on the hysterical that neither the book nor music ever come close to. The orchestra approached the score with a welcome “well, whatever it takes” slanginess, and the vocal talent was accomplished and often affecting. Special mention should be made of Christiaan Smith-Kotlarek, in the role of John Wilkes Booth, whose supple baritone held the whole thing together and whose wicked stage presence never failed to energize the audience. This was a professional production of a minor work, with real, if episodic, rewards.

Jeff Melnick is associate professor of American Studies at UMass Boston, where he specializes in twentieth-century US history. Melnick has published widely on American popular culture, immigration history, and Black-Jewish relations. His most recent book, 9/11 Culture, was published in 2009. Currently, Melnick is working on a project called “Creepy Crawling with the Manson Family.”

Director Jim Petosa

The selection of Assassins came as a direct result of the successful exploration of the Sondheim musical Merrily We Roll Along in 2010. Like that musical, Assassins seems to be a problem piece in that its 1991 Playwrights Horizons workshop production yielded an intriguing idea of a show that was somewhat abandoned after that exploration. The 2005 Roundabout revival, which provided some further development along with the addition of a new song, opened up more of the show’s potential, but still left us with something that seems not fully formed. Given the talents and curiosities of its collaborators, Assassins intrigued us. As a company, we became curious about the possibilities of exploring the relationship between the characters of The Proprietor and The Balladeer. The first is the one who arms the Assassins and prods them into their actions. The Balladeer, on the other hand, plays the role of folkloric historian, who maintains the repository of the American legend and diminishes the assassins’ impact. In this serio-comic Valhalla in which the assassins now reside, theatrically, for the rest of time, we watch them wrestle with their attempts to have an impact on how we, the audience, view their motives and their reasons to be. The Balladeer is ultimately co-opted by the gang of assassins and is transformed into the embodiment of Lee Harvey Oswald on the fateful day in November, 1963.

While the book and lyrics of the musical are full of actual bits of historically accurate information, the play is in no way intended as a history lesson. It does seem to be a study of the antithesis of the American Dream. It implies that the mythic basis for that American Dream, by design, leaves behind participants in an American Nightmare. That world is filled with the losers of a competitive society that is, from their perspective, happy to propagandize the notion that in America, anyone can attain what they want if they work hard enough or, in some cases, are lucky enough. (“In America, anyone can become President.”) The politics, anger, lunacy, and off-centeredness of our motley ensemble of assassins become a way into looking at ourselves.

Based on the five weeks of work that put me in collaboration with this generous and brave student company and design team, I believe that we discovered many ideas in the play that warrant further exploration in production. Like all of the explorations we undertake at the BU School of Theatre, the process of experimentation and discovery leads us to closed doors and/or open ones. In this case, we found more doors opening than were shut to us. I hope to someday continue that process of discovery with this provocative musical.

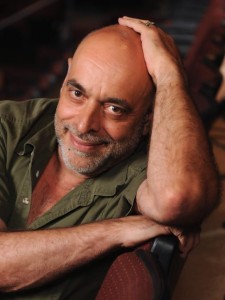

Jim Petosa has been the artistic and educational leader of the Boston University School of Theatre since 2002, and was recently named Artistic Director of New Repertory Theatre. From 1994 to 2012, he served as Artistic Director of Maryland’s Olney Theatre Center. In 2008, Petosa established the Boston Center for American Performance, the professional extension of the BU School of Theatre. He also serves as one of three artistic directors for the Potomac Theatre Project — PTP/NYC, a company devoted to the presentation of political works. In addition to Assassins, Petosa has directed many plays and operas, most recently Neal Bell’s Monster (BCAP) and Jeffrey Hatcher’s Three Viewings (New Rep).

Tagged: Assassins, Boston University College of Fine Arts, Jim Petosa, john-weidman