Theater Review: An Earnest “Troilus and Cressida”

By Bill Marx

We are a long way from the love-destroyed-by-hostility pieties of Romeo and Juliet, but Actors’ Shakespeare Project director Tina Packer wants to make the problematic Troilus and Cressida fit into that reassuring, touch-of-the-tragic mold.

Troilus and Cressida by William Shakespeare. Directed by Tina Packer. Presented by Actors’ Shakespeare Project at the Modern Theatre at Suffolk University, Boston, MA, through May 20.

My dear Telemachus,

The Trojan War

is over now; I don’t recall who won it.

The Greeks, no doubt, for only they would leave

so many dead so far from their homeland.From “Odysseus to Telemachus” by Joseph Brodsky

Brooke Hardman (Cressida) and Maurice Emmanuel Parent (Trolius) in the ASP production of TROLIUS AND CRESSIDA. Photo: Stratton McCrady.

Rarely staged, Timon of Athens and Troilus and Cressida epitomize a pessimism in Shakespeare’s work that grounds itself in an unsavory nihilism (some would argue cynicism, except we don’t like to think of the hallowed Bard that way), a savage and sour view of the world that deliberately eschews the tragic payoff of a King Lear or Macbeth. The whirligig of time is dead stuck, unaccompanied by complicating intimations of a stand-off between good and evil or poetic flickers of existential glamor.

Apparently, neither script was performed in Shakespeare’s lifetime, suggesting that they were (failed?) experiments in darkness crafted for a niche audience or non-box office expressions of the Bard’s private frustrations. Nothing wrong with blind alleys—they are an inevitable byproduct of genius. The minor artist “never risks failure,” argues W. H. Auden, “he keeps to one thing, does it well, and keeps on doing it.” A pretty good description of most contemporary playwrights, who shy away at tampering seriously with their brand.

What separates Timon from Troilus and Cressida is that the former is driven by an exhilarating if self-destructive anger that anticipates the death’s head satire of Swift, Céline, and Thomas Bernhard. The latter’s vision of an endless and absurd war that’s infecting its warriors with a morally corrupting disease feels more like a diagnostic study of duplicity as a form of debilitating contamination. (The play is also an examination of war and boredom—history indicates that those not busy killing the enemy find pleasurable ways to kill time.) Pandarus is the play’s two-faced guiding spirit, his demeaning guile a model for the Greek and Trojan military’s manipulative plots and amoral counter-plots, the latter including Achilles’s cowardly destruction of the noble but blind-to-reason Hector. The result is a weird but fascinating mixture of the seamy and the comic, the script’s sick humor revolving around how the meltdown of stale illusions of honor and love accelerates inhumane violence.

Ulysses’s famous speech about the enforcement of order through rigid hierarchy was undercut most memorably in my favorite production of Troilus and Cressida to date: David William’s 1989 staging at Canada’s Stratford Festival. The presentation was excoriated by the critics; Mel Gussow at The New York Times called it “aberrant.” But the controversial approach took the script to its logical conclusion, depicting the utter breakdown of proper “degree” in a predominately male world that is wallowing shamelessly in a fetish of sex and death—it was a wild, campy, decadent round-up of effeminacy and cross-dressing, occasional knife fights competing with seductions in latrines. A figure of delicately curdled beauty, Helen was wheeled about the stage in what looked like a giant, glittery Faberge egg. Yes, it was discomforting and disturbing—no doubt just what the Bard intended with this take-down of Chaucer.

In other words, we are a long way from the love-destroyed-by-hostility pieties of Romeo and Juliet, but ASP director Tina Packer wants to make Troilus and Cressida fit into that reassuring and earnest mold. In her notes for the program, she writes that beneath the macho rituals of degradation, Shakespeare explores “love between human beings being mashed up and obliterated in the desire for competition and winning.” Truth is, there’s precious little genuine love to be ground up amid all the mordant variations on betrayal in Troilus and Cressida. From the beginning, Troilus and Cressida focus on the changeability of passion, while Thersites, the truth-telling fool, communicates to all and sundry how horrible the war is, but his knowledge doesn’t rouse him into empathy. Instead, he rants of extinction (“Lechery, lechery; still, wars and lechery: nothing else hold fashion”) with the misanthropic pizazz of a Timon.

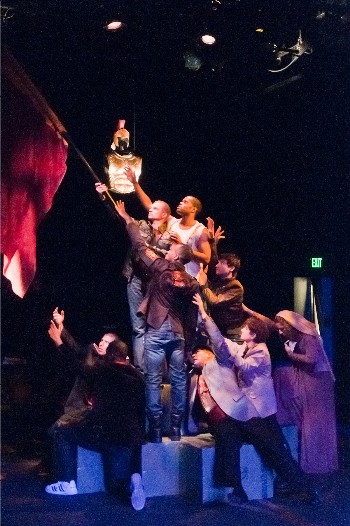

What Packer comes up with is a muscular, clearly spoken production that breaks into pieces (broad comedy alternates uneasily with anti-war didacticism), partly because it doesn’t want to deal with the clownish ugliness of the script. Shakespeare is exploring what happens in combat when, despite patriotic lip-service, winning becomes besides the point. Packer is looking for victims in a play that doesn’t have any.

The performances don’t build into powerful wholes. Robert Walsh’s Pandarus comes off as an audience-pleasing vaudevillian gone to seed in the first half and then flips into plague-ish exhaustion (second banana gone to rot?) by the end of the play. The challenge here (as in most of the rest of play) is for the actors to fuse the rancid and the jokey throughout. Brooke Hardman doesn’t suggest Cressida’s flightiness—she just jumps from finally admitting her yen for the worshipful Trojan Troilus to dumping him once she is taken into the Greek camp, while Maurice Emmanuel Parent makes for a pleasantly callow Troilus, though he doesn’t generate the necessary chill when, disappointed in love, he turns into a killing machine in the image of the Greeks. Paige Clark plays a number of the female roles in cartoon mode—a silly sexpot of a Helen, an overactive Cassandra and Andromache, wife of Hector. (Why are Cassandra figures always played over the top, either shrieking haplessly around the palace or speaking in a spooky manner—wouldn’t a matter-of-fact delivery of a message from the onerous future be more chilling?)

Things are not working out for Cressida (Brooke Hardman) in the ASP production of TROLIUS AND CRESSIDA. Photo: Stratton McCrady.

More effective are some of the portrayals of the Greek and Trojan soldiers, especially Ross MacDonald’s nicely calibrated Hector, De’Lon Grant’s spoiled-to-the-max threat of an Achilles (the actor suggests a repressed sadism looking to be unleashed), and Danny Bryck in a number of roles, most memorably as Patroclus, Achilles’s lover. Johnnie McQuarley, a locker-room blowhard of an Ajax, and Bobbie Steinbach, taking on the roles of King Priam and Nestor, an aged Greek Commander, lean toward disappointingly flat caricature. In suit and tie, Craig Mathers paints Ulysses as a corporate type who preaches conventional “everything in its proper place” wisdom (it is the best way to keep the troops in line) but embraces devious scheming, though it seems to me the Machiavellian character (a dramatist manqué?) should enjoy playing the puppet master more.

Lean and mean, the production moves along with dispatch, and Packer has fun with the intimacy of the Modern Theatre stage space, the actors addressing the audience (Pandarus drums up business) or scurrying up the aisle. Troilus and Cressida isn’t staged often, so for that reason alone it is worth seeing the uneven ASP presentation, but the play’s sardonic vision calls for a more robustly radical treatment than turning it into a bumpy, roughed-up retread of Romeo and Juliet.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: ASP, Actors' Shakespeare Project, Tina Packer, Troilus and Cressida