Book Review: Beyond Plums and Wheelbarrows — A New Biography of William Carlos Williams

For the reader who is not already a William Carlos Williams enthusiast, the biography provides a good corrective to the Norton Anthology picture of Williams as the poet of tiny images, of plums and red wheelbarrows and fire engines with big, gold letters.

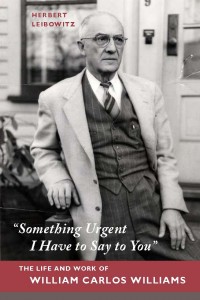

Something Urgent I Have to Say to You: The Life and Works of William Carlos Williams by Herbert Leibowitz. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011, 496 pages.

By Maryann Corbett

What may a biographer use as the evidence for an author’s thoughts? When can a scholar validly claim to have gotten inside his or her subject’s head? Most biographers leave these basic questions unasked, hoping that readers will be trusting and that only the best-informed reviewers will pierce the veil of guesswork. Herbert Leibowitz, the editor of Parnassus: Poetry in Review, puts the question front and center.

The method he presents is unconventional: to write the life of the poet William Carlos Williams, he will use not only the abundant usual sources—autobiography, essays, interviews with the poet and those who knew him—but also close readings of the poems and stories. And he lets us know at the outset that he means to get under the surface of the work, to know the poet’s mind better than the poet knows it himself.

For this method of working, he first offers what seems to be a model case: his analysis of the long poem “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower.” He begins with observations about Williams’s life circumstances at the time the poem was written: after a life of infidelities, Williams had suddenly been disabled by two strokes and was completely dependent on the care of his wife, Floss. The balance of power in their marriage had shifted; the poet had reasons now to feel guilt and to attempt to make amends.

Looking at the poem through the lens of those facts, Leibowitz finds it awkward, insensitive to the point of cruelty, and dishonest. Leibowitz is a skillful, practiced close reader, sharp-eyed and, here, sharp-tongued. Writing about what might seem a transparent detail, the poem’s step-down tercet form, he says,

While periods and commas lightly dot the highway, Williams frequently runs stop signs. Wherever he decides to exit a topic because he can’t bear the humiliation of his mea culpa, he slams on the brakes and veers off-ramp into a public reference, a historical citation, an aphorism about poetry, a remark about art, a hodgepodge of memories. . . .

In sum, Leibowitz calls the poem “so clumsy that one wonders what was blocking [Williams’s] ear and his critical faculty.” This is a very unusual take on a poem that has been praised early by Auden (“one of the most beautiful poems in the language”) and late by Wendell Berry (the lines’ “meaning is incarnate in what the poet has imagined and made, and what they say could have been said only in this poem”) and often in the interim.

By putting this ringing challenge at the beginning of the book, Leibowitz seems to be declaring that all his treatments of Williams’s writing will do this kind of shake-’em-up psychoanalysis. His opening chapter, “Poetry as Evidence for Biography” looks and feels like a journalistic hook for the rest of the story. But that initial declaration is oversell. Despite Leibowitz’s apparent claims, many of the book’s discussions of the poems, novels, and short stories do just what literary biography ought to do and ordinarily does. They treat the works as evidence for Williams’s place in the history of literature. They illustrate his beliefs about poetry, his wildly uneven poetic production, his view of himself as a writer, his goals for his own poetry and American poetry as a whole, and his relationships with other writers of the period, friend and foe.

This is an easy point to check, because the book works the way a good biography should. It’s well indexed and well annotated, with the usual careful scholarly apparatus. These tools make it easy to dip into the book and examine Leibowitz’s treatments of individual poems and books, as well as Williams’s dealings with specific people and events. Yet the whole is not so overwhelming in its detail as Paul Mariani’s 874-page biography published in 1981. Detail and fine-grained indexing are the servants of the researcher who wants to check a particular point rather than to read a whole book, and the Mariani book serves me better if I want to ask questions about (for example) the Modernists’ early decision to dispense with line-initial capital letters and so want to find out more about the little magazine Others. The scholarly Mariani gives me more to work with.

Leibowitz, by contrast, charges ahead like a good large-class lecturer. He covers the big picture: Williams’s role in the important movements of the early twentieth century, his experiments, his uncertainties, his way of making a poetic life fit into the demanding full-time work of a busy, local doctor. He also slows down for particular books and poems. For the reader who is not already a Williams enthusiast, Leibowitz provides a good corrective to the Norton Anthology picture of Williams as the poet of tiny images, of plums and red wheelbarrows and fire engines with big, gold letters. He places the plums and the wheelbarrow in their context within the larger work Spring and All. The poet of the long works like Paterson, and of combinations of prose and poetry such as In the American Grain, gets a full presentation. We see the experiments, wanderings, and unreliable quality of much of the poetry. Because Leibowitz treats the works out of order—using the later poems in his introductory arguments and in his examination of Williams’s forebears—he seems to neglect Williams’s late style. But Pictures from Breughel gets close attention and in its right place.

It’s true that reviewers have objected to the extent of Leibowitz’s “reading into” the poems. Daisy Fried notes that what’s done in a poem is done for art, not for biographical accuracy. (Fried, by the way, chides Leibowitz as if he alone were responsible for the fundamental idea of looking at the life with close attention to the work. But the book’s acknowledgments make clear that the idea originated with the late James Laughlin, who had been Williams’s friend and his publisher at New Directions.) And more than one reviewer has taken issue with Leibowitz’s concentration on Williams’s sex life. On that subject, I wonder if Leibowitz’s decision to begin on the note of adultery has skewed reviewers’ reactions. An emphasis on sex may be unavoidable when writing about this life. If I compare the indexes of the Leibowitz and the Mariani books, I find in both under “Williams, William Carlos” a subheading beginning with “sex” that extends for seven full lines of undifferentiated page numbers.

Reviewers have also pointed out certain inaccuracies. The most disturbing charge (Fried’s) in a book that concentrates on close reading is incorrect lineation in a number of the poems. This is a blot on the publisher rather than the author. Another gotcha is a demonstration that Leibowitz was mistaken to trust in the poet’s own memory of whether he’d been at the Armory Show opening, when his wife’s memoirs testify that he went to the show later, not on its opening day. There is also the claim (by Grace Cavalieri) that, in describing the life-background of the poem “Danse Russe,” Leibowitz has missed information supplied in the 1975 biography written by Reed Whittemore. Slips like those should put us on guard.

But for nonspecialist readers, the book is a good read, in spite of the vertiginous changes of focus between close reading and life-narrative. The life is there and in more than outline. The treatments of literary cooperation and conflict crackle with interest—for example, the excerpts from letters written to Williams by his prickly and difficult friend Ezra Pound:

And America? What the h—l do you a blooming foreigner know about the place. Your père only penetrated the edge, and you’ve never been west of Upper Darby, or the Maunchunk switchback.

Would H., with the swirl of the prairie wind in her underwear, or the Virile Sandburg recognize you, you effete easterner as a REAL American? Inconceivable!!!!!

And the people around Williams at all stages of his life, both the famous and the anonymous, are given vivid life. We get the cattiness of H. D., for example, in gossipy letters to one of Williams’s pre-Floss loves (“By the way, I thought Williams most banal. Don’t tell him so, of course. . . .”) and the vehemence of Bill Jr., Williams’s son, who greets Leibowitz with “If you’re a bloodhound come to sniff out my father’s affairs, well, there weren’t any.”

This is what we come to biography for. We want a sense of the writer’s life as it felt when lived, and we want claims, risky though they are, about what the writer was thinking. Readers will inevitably disagree about whether Williams was really as concerned and conflicted about his sex life as Leibowitz believes, since all any biographer can do is round up materials—and for Williams they are copious—and begin digging. What Leibowitz presents is a picture that we can take in, a critical view of Williams that puts flesh on the average reader’s bare-bones image. Is it all absolutely, definitively correct? As a little blurb on Arts & Letters Daily read not long ago

“Homework and guesswork, reconstruction and speculation: That’s always been the stuff of biographies. Still is.”

Maryann Corbett is the author of Breath Control, just out from David Robert Books, and the chapbooks Dissonance (Scienter Press, 2009) and Gardening in a Time of War (Pudding House, 2007). She has been a winner of the Willis Barnstone Translation Prize and a finalist for the Morton Marr prize, the Best of the Net anthology, and the Able Muse Book Prize.

Her poems, essays, and translations have appeared in many journals in print and online, including River Styx, Atlanta Review, The Evansville Review, Literary Imagination, Subtropics, and The Dark Horse, as well as The Able Muse Anthology, Hot Sonnets, and the forthcoming Imago Dei: Poems from Christianity and Literature. She lives in St. Paul and works for the Minnesota Legislature.

Tagged: Herbert Leibowitz, Something Urgent I Have to Say to You: The Life and Works of William Carlos Williams

They never get inside our heads; but the more they put the writing at the center of the life, the more likely they are to get it right.