Theater Review: Viva The Andersen Project — The Loneliness of Making Art

Director Robert Lepage’s The Andersen Project is a masterful meditation on the agonizing process of artistic creation. Few scripts bring the mixed essence of opportunism and magic of show biz together so effortlessly.

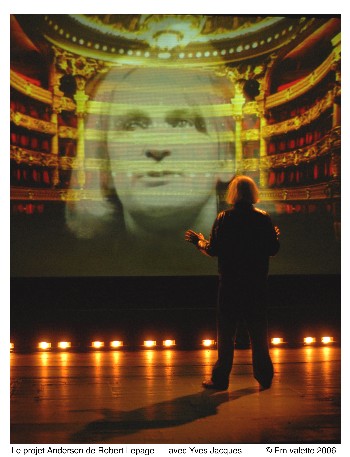

The Andersen Project. Written and directed by Robert Lepage. Performed by Yves Jacques. Presented by Arts Emerson at the Cutler Majestic Theatre, Boston, MA, through April 1.

By Bill Marx

The Arts Emerson advertisements bill Robert Lepage’s The Andersen Project, a 2005 piece commissioned by Denmark as part of the 200th anniversary celebration of the birth of Hans Christian Andersen, as a “fairy tale for adults.” But it is less about enchantment than an edgy opera boffo about the aborted writing of an opera. The lonely, sexually repressed life of Andersen, a master of conveying yearning fantasy, triggers in Lepage a playful meditation on the sour machinations of making art in today’s monetized world, a wonderfully wild tale of still-born creation conveyed through bursts of a dazzling, cinematic theatrical imagination that ranges from Parisian peep shows to surreal scenarios featuring a dyad willing to die for a chance to experience a night in Paris. The result is a marvelously melancholic yet exhilarating fable that is finally receiving its Boston premiere—Lepage is one of the leading stage directors around, and he has made far too few appearances here. (I vividly remember the ethereal beauty of the images in his The Far Side of the Moon, which came to the American Repertory Theater in 2005.)

The one-man show features the chameleonic Yves Jacques—making some amazingly quick costume changes—playing a number of roles, principally the show’s anti-hero, Fredric, an albino rock and roll lyricist from Montreal who has broken up with his girl friend of 16 years, and Arnaud, the fast-talking administrator of an opera company who invites Fredric to write the libretto for a children’s opera based on an obscure Hans Christian Andersen story. Jacques also plays Rashid, a Moroccan janitor (and graffiti artist) who mops up after clients at a peep show that is located on the first floor of the same building that houses the apartment Fredric is subletting.

Part of what fascinates Lepage is how the intersection of the different worlds of these characters lead to revelation and eventual failure: the collision of ambition, reputation, and fear brings about a confrontation with dark realities. For Arnaud, his marriage is falling apart as he finds himself unable to deal with his sexual addictions, while Fredric wants to find validation by going outside of his comfort zone (the “provincial makes good” scenario) by creating an opera in Paris. The upshot is that the isolated Andersen, who walks through parts of the play as a sort of prophetic muse, comes off as an admirable figure whose life and stories offer the solace of hard truth—loneliness is a virtue.

For the sake of keeping the budget low, Fredric is asked to adapt the Andersen tale “The Dryad” for a single voice. The yarn revolves around a tree nymph who sacrifices a long life in the woods for a visit to Paris. The tale parallels the “fish out of water” alienation of the play’s characters, who mistakenly think that they can have what they wish for. Despite the piece’s sense of futility, Lepage has a lot of satiric fun with his characters’ desires and self-importance, most hilariously in Arnoud’s hilarious monologue, a furious amalgamation of words reflects the gossip, ego, money, fashion, corruption, and whimsy in the international art world. (It is a gathering of pretentious talk that Lepage knows well.) Fredric’s visit to a dog psychologist who isn’t interested in the pet’s hangups is a sardonic delight, while there is plenty of dreamy beauty to be had in the depiction, using pictures and puppets, of snatches of The Dryad. The flow of images, the nimbly choreographed interaction of actor and screen, accrues a musical rhythm, images changing locale and perspectives on a dime.

Though Lepage is merciless on his characters and their self-delusions—his lack of sentimentality is bracing—the tremendous visual imagination of his staging, with its scintillating swoops and dips, offers more than enough inspiration.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.