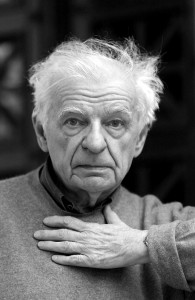

Poetry Review: Yves Bonnefoy — A Provocative “Second Simplicity”

This handsome edition of Yves Bonnefoy’s recent poetry and prose in English translation is a stunning presentation of a major poet.

Second Simplicity: New Poetry and Prose, 1991-2011 by Yves Bonnefoy. Translated from the French by Hoyt Rogers. Yale University Press, 320 pages, $30.

By Jim Kates.

Last fall, when it was announced that Tomas Tranströmer (Arts Fuse commentary) had won the Nobel Prize for literature, headlines in the United States were confounded. As usual. In a ritual dance common enough to be an essential part of the Nobel ceremonies, a general cry went up, “Who is this guy? We’ve never heard of him!” And within an all-too-small circle of literati, a more self-satisfied, triumphal jig —- we know who this guy is, we can debate his work and merit.

Among those other “guys” who are internationally but not popularly recognized in the United States, the French poet Yves Bonnefoy stands high on the list. For decades now, Bonnefoy, who is approaching 90, has been considered pre-eminent in his own country and throughout Europe. He is an accomplished translator of Keats, Yeats, and Shakespeare, among others, and equally fortunate with those who have translated him. Nor can we claim that he has been somehow sheltered from the English-speaking world in person. He has resided in the United Kingdom and in the United States from time to time.

Still, I suspect that all too many readers will cry out, if they come across Second Simplicity: New Poetry and Prose, 1991-2011 in their bookshops, as I hope they will, “Who is this guy?” It’s about time they found out.

Therefore, it is very good news that this handsome edition of Bonnefoy’s recent work in English translation is now available to us and that it is a stunning presentation of a major poet. Second Simplicity not only updates our access to Bonnefoy—even better, the editor-translator Hoyt Rogers provides a comprehensive bibliography of existing English translations, generously acknowledging all those who have labored in the same vineyard. For this largesse alone, thank you.

Rogers has proved his qualification for the work. He knows Bonnefoy’s poems and translations intimately, has worked with the poet, and has published a previous book of translations of Bonnefoy (The Curved Planks, 2006) in which he thoughtfully laid out his own engagement with the process of translating Bonnefoy. “At the author’s request, I have avoided relying too heavily on such well-worn approximations . . . instead I have varied the solutions, sometimes in a way that may seem unorthodox” (The Curved Planks). In his comprehensive introduction to Second Simplicity, he concentrates on introducing the poet, however, not himself:

Bonnefoy’s writing has evolved toward a “second simplicity” of imagery and diction. He has whittled his tropes and phrases in order to arrive at the sheer essence of each text. This quality is the opposite of simplemindedness: what has come “second” is a distillation of the many decades of rigorous thought that have gone before.

As Second Simplicity (like the best of earlier editions of Bonnefoy translations) is a bilingual edition, a biingual reader has the opportunity to play Rogers’s translations off against the originals, and a monolingual reader can be reminded on every page of the contingency of Rogers’s work even while reveling in the English. Neither reader will be disappointed in “a here that breathes the elsewhere in and out, a medusa as large as a sea—which would be the world” (Second Simplicity).

That single image demonstrates both Rogers’s work and Bonnefoy’s. The translator is not afraid of the cognate, which may be more elusive for the English-speaking reader but which is also more allusive and mellifluous, “medusa” instead of “jellyfish”; while the poet luxuriates without self-indulgence in a modulation between abstraction and a real world he shares unstintingly with his readers. Or, as John Taylor has put it (in his critical study Paths to Contemporary French Literature), Bonnefoy is one of those “in effect autobiographers who are seeking rigorously . . . to get beyond the borders of the self and no longer be auobiographers, as it were; or at least not self-centered observers.”

This becomes even more apparent where Bonnefoy’s verse spills over into prose, both in his prose poetry and in his more straightforward essay “Three Recollections of Borges,” wherein the “simplicity” of his own title is obliquely glossed:

Borges spoke without notes, since he couldn’t use them. In fact, he didn’t go on for long: from time to time, he picked up a large watch from the table, holding it close to his eyes. Once again, he expressed himself with what appeared—to me, anyway—like a simplicity meant to provoke.

“A simplicity meant to provoke” pervades Bonnefoy’s poetry but with an extreme delicacy that eliminates one kind of provocation—it is all a calling forth rather than a sting:

Since fire is born of fire, why should we want

To gather up its scattered ash.

On the appointed day we surrendered what we were

To a vaster blaze, the evening sky.

I confess as a reviewer that I have not yet sat down and read Second Simplicity straight through, as I ought. Instead, I have hovered and dipped among the selections from this last decade of Bonnefoy’s work and surely still missed much; but the book itself, it seems to me, calls for that light touch. (The word “delicacy” above was not loosely chosen. For me, it characterizes Bonnefoy’s work more than any other.)

The excerpts I have returned to again and again are in the selection from “La Longue chaîne de l’ancre” (“The Anchor’s Long Chain”) with its mix of history and geography, of formal verse and languorous prose. But the rest of the book is no less beguiling, and readers will be well launched (maritime imagery pervades Bonnefoy’s work) wherever they begin.

As though we know

All origin is a Troy that burns,

All beauty but regret, and all our work

Runs like water through our hands.

Tagged: 1991-2011, French poetry, Second Simplicity: New Poetry and Prose, french, translation

Bonnefoy has not only translated the plays of Shakespeare, but has also written some first-rate criticism of them, available in translation in the volume Shakespeare and the French Poet from University of Chicago Press. Here is an interview where Bonnefoy talks about Shakespeare with John Naughton, the volume’s translator.

Wow: the idea of Keats in French.