Film Review: “In Darkness” — Not Just Another Holocaust Movie

Twenty-one years after she received a Golden Globe for Europa Europa, director Agnieszka Holland returns with another uncompromising vision of perseverance and the power of human connection in the worst of times.

In Darkness. Directed by Agnieszka Holland. At the Kendall Square Cinema and the West Newton Cinema.

By Tim Jackson

In June 1941, thousands of Jews living in Lvov, Poland were massacred by invading Nazi troops. By December 150,000 more had been thrown into newly established ghettos or exported to camps. The city, which had been the third largest Jewish community in Poland and a cultural and industrial center, descended into a hellhole of murder, random violence, and brutal intimidation. In Darkness, directed by Agnieszka Holland, tells the story of a small group of Jews, including seven-year-old Krystyna Chiger and her four-year-old brother Pawelek who, during this Nazi occupation, survived for 14 months in the sewers of Lvov. They were aided by Leopold Socha, a smuggler and thief who was making a living scurrying away treasures and selling confiscated property.

It is a story of mutual survival and of humanity stripped to the core and ultimately the redemption of Socha. Twenty-one years after she received a Golden Globe for Europa Europa, her remarkable film about a German Jew who hides his identity by joining the Nazi Youth, the director returns with another uncompromising vision of perseverance and the power of human connection in the worst of times.

As the film begins, the audience is immediately thrown into the hallucinatory madness of Nazi occupation and into the literal and figurative darkness of survival on and below the streets. The sewers are a maze of pipes and putrid water—cold, dark, and teeming with rats. Yet the group endures these impossible conditions. The hand-held camera crawls low through the damp crevices of the winding sewers illuminated by candles and small lamps. Neither the characters nor the audience are quite sure where they are or of what might be coming next—a Nazi search to a raging flood of rainwater. From above we hear occasional gunshots, falling bodies, carts, and at one point, church music. The group adjusts to sharing the space with rats, to the stench, to the cold. A child plays with a truck on the wall of the sewer. A young girl performs a song, briefly reviving the group’s humanity. A couple makes love in the damp night under piles of worn blankets, while another of the women secretly watches. Prayers are offered, stories read. There is even a birth. Humanity endures.

Holland’s deft and visceral directing style draws attention to the physicality and humanity of her subjects, to the textures of the spaces they inhabit, to skin, eyes, gestures, and to the wildly shifting temperaments of people caught in situations beyond imagination. The editing deliberately provides stark contrast between life below and the meager and harrowing life above. Who is able, or even willing, to retain their dignity? Above ground the citizens all have their eyes and ears out. Anybody could turn them in, and there is money to be made turning in Jews. The temptation to turn from one’s conscience or give in to one’s prejudice or desperation is constant. Below there is humanity and hope. The line between good and evil is thin during such times.

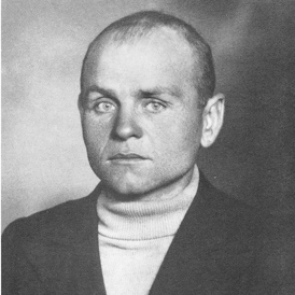

The cast of primarily Polish actors brings an urgency and realism to the roles. Holland wisely leaves the dialogue primarily in Polish, though many languages are used. Mundek Margulies, the rugged organizer at the center of the group, is played with charisma and determination by German actor Benno Fürmann. Polish actor Robert Wieckiewicz is completely believable as the puffed-up and ignorant Leopold Socha, whose posturing and arrogance give way to a greater wisdom. Watching a great performance by this unfamiliar actor lends authenticity to the role. Socha has a peculiar ambivalence and pride towards those he calls “my Jews.” It is not pity he feels, and money is his first motivation. We believe this character who surprises himself as he finds a deeper human connection and dignity as his own evolution becomes the film’s narrative center.

In fact, none of the characters are portrayed merely as victims. Each individual is played to show a range of strengths and flaws. They argue, fight, love, and inevitably go slightly mad. Above ground, Socha’s wife can give him a lecture on how all people are the same under the skin, until she finds he may be harboring Jews. Neither she nor her husband understands their own contradictory feelings.

Much credit should go to Polish cinematographer Jolanta Dylewska, who creates rich compositions with darkness and light in muted shades of brown, grey, and green. Using the famous “Red Cam” (none of the film is actually shot on celluloid), “darkness” becomes a larger metaphor for the Jewish condition. Her aim was to have the audience feel “touched by that darkness.” Socha, on whom everyone’s fate will ultimately depend, is always followed with light; his redemption is the film’s theme.

Tragedy and horror on such epic scale needs to be reduced to human terms to be understood. There is a possibility for love and human decency in the midst of evil. In Darkness doesn’t judge the relative worth of good, nobility, or the degree to which evil can flourish. Conflicts today from Rwanda to Bosnia should be recognized on a continuum of holocaust. This is not just a “holocaust movie.” Films can celebrate survival and deplore evil, but as In Darkness makes clear, it is love and human connection that will carry us on.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Great review. I want to see this movie!