Jazz CD Review: The Dominique Eade Quartet at Scullers & Ran Blake / Dominique Eade CD, “Whirlpool”

Dominique Eade’s two greatest gifts are her clarity of musical thought and her courage as an improviser. She does not try to be a cabaret-style interpreter or a ring-a-ding-ding swinger.

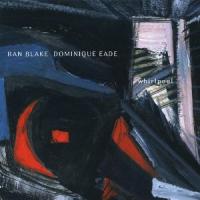

Whirlpool by Ran Blake and Dominique Eade (Jazz Project).

By Steve Elman.

Sidestepping all the issues of jazz and not-jazz, there are relatively few paradigms for female singer and ensemble. She can be the singer-songwriter, or the diva, or the sex goddess, or the chick chirp, or the living symbol of decay, or the boss of the band, or one of the guys.

Dominique Eade is none of these things, and hearing her in a quartet (with tenor, guitar, and bass) on February 9 at Scullers and in a duo (with pianist Ran Blake) in the new CD Whirlpool, proves once again how hard it is to characterize an artist who makes her own way.

She is fearless: in her Scullers show, she spanned 900 years of influences, from medieval composer Hildegard von Bingen to R&B diva Aretha Franklin. She is unpretentious in her musical sophistication: at the end of the first number at Scullers, she tossed off the fact that she had combined the verse from the Vincent Youmans/Irving Caesar tune “Tea for Two” with Thelonious Monk’s “Skippy,” noting in passing that Monk had based his tune on Youmans’s chord structure (an observation that was news to me). She has fun: her duo with bassist John Lockwood on the Jimmy van Heusen/Sammy Cahn ditty “The Tender Trap” was so fast that words were swallowed and pitches blurred, all in a kind of burlesque of what is a rather silly song. She is an effortless leader: each of her three companions was obviously delighted to be working with her, and each provided both sympathetic support and sparkling solo turns.

Eade’s two greatest gifts are her clarity of musical thought and her courage as an improviser. She does not try to be a cabaret-style interpreter or a ring-a-ding-ding swinger. Instead, she delves into a song with beginning-to-end exploration, including extended passages of smart scat, or clever lyric / harmonic substitutions, or semi-spoken notes, or Sheila-Jordan style musical monologue. Sometimes you don’t grasp the full implications of one of her performances until she reaches the very last note.

She has a thrilling voice and remarkable control. She doesn’t possess a perfect instrument, but it’s a beautiful one nonetheless. Like all voices, hers has tiny rough spots, places where going from pitch to pitch is a little more troublesome than it is at others. Most singers try to disguise these flaws or distract you from them with vibrato or volume or other sleights-of-voice. Eade is less concerned with such trickery because she is so concerned with music; as a result, her work is more human than that of many other singers, and it’s more profound than that of most.

And she is superbly flexible. At Scullers, she adjusted her vocal tone to harmonize gorgeously with Donny McCaslin’s upper-register, tenor sax birdcalls and alternately with Brad Shepik’s buttery guitar lines. On the recording with Ran Blake, she called forth a pure sound that glistened like a gem on Blake’s dark cushion.

I think that the Blake/Eade date (Whirlpool, Jazz Project, 2011) will stand as a landmark in both artists’ discographies. To my knowledge, there are only three other Ran Blake recordings that are completely devoted to duets with singers. There are two with the late Jeanne Lee (You Stepped Out of a Cloud, Rhino, 1991; and The Newest Sound Around, RCA, 1961). The third is a session with Christine Correia (Roundabout, Music & Arts, 2006), which I have not heard.

Whirlpool is the result of two recording dates made four years apart (2004 and 2008). I can’t imagine why it took nearly four more years for the CD to appear, but as it happens, this release marks Blake’s 50th anniversary as a recording artist, and it rounds his career nicely, since The Newest Sound Around, Blake’s first duet with Lee, was his debut on vinyl.

By now, the world divides neatly into two groups—those who love Ran Blake’s work, and those who say, “Ran who?” Since my subject is primarily Eade, I’ll let you pick up the nuances as we go along, but for those who are in Group II, I’ll just say that Blake is the only jazz piano virtuoso who makes atmosphere his primary aesthetic goal. You will listen in vain if you expect him to compete with Fats Waller or Oscar Peterson or Keith Jarrett in a fingerbusting joust; conversely, you will never find Fats or Oscar or Keith exploring the piano or the human soul as distinctively as Blake does. What he does is without parallel. To hear him for the first time is to realize how limited is our understanding of what music is and what it can be.

The repertoire on the new release is a very satisfying mix of great standards (“My Foolish Heart,” “Old Devil Moon,” “Dearly Beloved”); familiar stuff from Blake’s book (Alfred Newman’s “Pinky,” the only wordless vocal on the disk, and the Quincy Jones/Jack Lawrence theme from the movie The Pawnbroker); an Eade original (“Go Gently to the Water”); and the kinds of oddities that Blake loves to refashion (“After the Ball,” written in 1891, and “Falling,” a 1955 tune recorded by Stan Kenton’s band with Ann Richards and written by Zan Overall, who has since become (in)famous as a “holocaust revisionist” and supporter of the theory that the Israeli Mossad was responsible for the 9/11 attacks).

Each one of the performances here is a mini-drama. In fact, listening to the CD straight through dulls the edge of each individual song, and, when you acquire it, I would advise you to take a deep breath, or a contemplative sip of wine, or a short walk, between each tune.

If you have no familiarity with either Blake or Eade, start with “Old Devil Moon.” This very familiar tune by Burton Lane and Yip Harburg begins conventionally enough, though even a bit of deep listening to Blake’s accompaniment reveals that he’s nudging the chords into places Lane never intended. When Eade gets to “You’ve got me flyin’ high and wide, on a magic carpet ride, full of butterflies inside,” Blake departs completely from the written harmony and tone-paints a swirl of dangerous, ascent-into-the-maelstrom chords to illustrate the singer’s confusion, and Eade responds by flattening the last written note of “inside” to a hard dissonance, leaving the listener with a feeling of deep disquiet. Blake’s mid-tune solo is distinguished by effects that are his and his alone. There are moments where he fogs the chords in his left hand while making individual right-hand notes snap out like firecrackers; near the very end of the solo, there’s another signature moment, a kind of choked scream of a chord that shows how ingeniously he uses the piano’s pedals.

Eade’s chorus after the solo is much more adventurous than the first one, wilder, farther from the moorings of the harmony. Things come back together, sort of, in the last few seconds, as Eade holds the last word (“eyes”) steadily while Blake mutters darkly beneath her. Then, suddenly, she drops a zigzag of three off-harmony notes, and Blake punctuates them with a tiny cold comment.

Dominique Eade -- sometimes you don’t grasp the full implications of one of her performances until she reaches the very last note.

There are several of these spectacular endings. The final moments of “The Wind” are particularly powerful, ending with one of Blake’s “hidden chords,” where he sets up a harmony in advance using the piano’s often-neglected middle pedal, and it emerges as a kind of eerie echo after Eade stops singing. “Falling” is even more ominous; it’s ostensibly about heartache at the end of a love affair, with the last lines of the lyric wrapping things up in a Tin-Pan-Alley sort of way (“I don’t know what these dreams of falling mean / I wonder if someday they might come true / I only hope it means I’m falling out of love with you”).

But when Blake and Eade finish the tune, they drop the “falling out of love” line, leaving the impression that the “dreams of falling” might come true through the singer’s suicide. Or could they be thinking of the songwriter’s 9/11 opinions?

Eade’s “Go Gently to the Water” is lighter, where Blake sets up an aqueous atmosphere and Eade sounds a bit like the English chanteuse Julie Driscoll Tippetts. And “After the Ball” is a great closer—Eade singing the melody more or less straight, with Blake gradually taking the schmaltz-waltz feel into darker and weirder territory, a kind of chamber version of Ravel’s “La Valse.”

Blake was on hand for Eade’s set at Scullers, and she dedicated a sensitive performance of “Lover Man” to him, calling him a mentor. Guitarist Brad Shepik was her only accompanist on this one, and he translated some of Blake’s piano effects to his own instrument—a feat that I would have thought impossible if I hadn’t heard it.

Other memorable moments from Scullers: Donny McCaslin’s remarkable tenor sax solo on “All the King’s Horses”; the McCaslin-John Lockwood duet on “Yesterdays,” where the bassist drew on his long experience with The Fringe, nudging McCaslin out into semi-free territory and back again; Brad Shepik’s solo on “There Will Never Be Another You”; the reharmonization of the same tune (did Dominique sneak Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation” in there somewhere?); and Eade’s musical monologue in “Happiness,” where she said, “They say it’s 97% illusion, but I don’t mind.”

Best of all were Monk’s “Skippy,” a fiendishly tough line, sung wordlessly by Eade and played by the other three with remarkable aplomb, and Jimmy Webb’s “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress,” a cohesive ensemble performance that edged towards a country feel without ever getting sentimental.

There’s only one thing left to mention: Dominique Eade’s smile, which comes out sunnily whenever things are going well on the stand. She smiled a lot at Scullers, and I suspect she was all smiles recording with Ran Blake.

Dominique Eade’s website.

Ran Blake’s website.

(An idiosyncratic selection of Blake’s other CDs recommended by Steve Elman: Breakthru [IAI, 1976]; Suffield Gothic [Soul Note, 1984]; Duo en Noir with Enrico Rava [Between the Lines, 2000]; Sonic Temples [GM, 2001])

Brad Shepik’s discography, from his website.

(Recommended by Steve Elman: Drip [Knitting Factory, 2003])

Donny McCaslin’s discography with music samples, from his website.

(Recommended by Steve Elman,from McCaslin’s tenure with Dave Douglas: Meaning and Mystery [Greenleaf, 2006])

Re: John Lockwood . . . if you Google “John Lockwood” and “bass,” you will find his Berklee biography, sites devoted to The Fringe—and 108,000 more hits.