Book Review/Commentary: Why Lionel Trilling — and Serious Criticism — Matters

The essential task of the critic is not to like or dislike the arts or to push bromides, such as to celebrate the “power of reading.” Despite some troublesome modifications, Lionel Trilling carries on the mission of E.A. Poe and Henry James: he articulates the value of the serious act of judgment in a culture hostile to it.

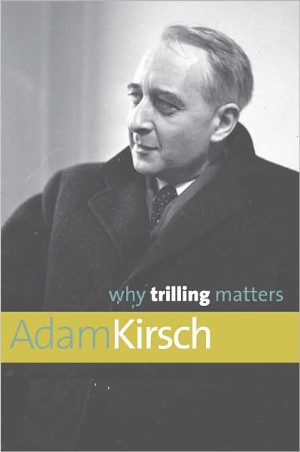

Why Trilling Matters by Adam Kirsch. Yale University Press, 185 pages, $24.

By Bill Marx

The threats against meaningful criticism of the arts are many, and they are posed by its ostensible friends as well as its obvious enemies. The confusion of snark and opinion for judgment on the Internet, the explication-only slant of academic criticism, the thumbs-up mania of commercial culture, all pose a challenge to a journalistic ideal of criticism. We have arrived at a time when readers, writers, and editors (as well as many critics) no longer know what criticism has been and have not figured out what it is supposed to do in an era of smartphones. Faced with such formidable ignorance and challenges, wind-baggy intonations of the “great” critical names—Matthew Arnold, S. T. Coleridge, and Samuel Johnson—are the equivalent of spitting into a hurricane.

Foes target the foundation of criticism: it is an act of independent and honest judgment. But the elemental responsibility of rendering a rational verdict, then supplying reasons and analysis to back up what may be tough evaluations (mediocrity has and always will predominate), cuts against our age of marketing. Selling the “Daily Me” prevails. And the power of advertising knits together the components of an increasingly niche-ridden culture. What unites mainstreamers, bohemians, NPR-worshipers, hipsters, and the art crowd? A disdain for critical evaluation. Why? It is bad for business—creators of all makes and sizes are part of an industrial cultural complex that (perennially) sees itself as on the ropes and whose prime directive is to distribute its wares to as many as it can. The substandard exists, but specifics are not to be scrutinized in polite company.

Thus Adam Kirsch’s clear-headed book about the esteemed American critic Lionel Trilling comes at a propitious time. I want to concentrate on how the volume suggests Trilling’s writing could be of use in refurbishing criticism today and in the future. Not only does Kirsch rightfully argue that the craft of serious literary criticism deserves respect for its own sake, but it posits, through Trilling’s admittedly fraught Cold War warrior example, a definition of criticism that contradicts the current sunny-side up, let-us-service-your-sensibility mode of evaluation. In his 1965 essay “The Two Environments,” Trilling sums up, as Kirsch rightly notes, “the whole career of the culture industry from then to now”:

The economy itself is deeply involved with matters of style and with conditions of the spirit or psyche. Our commodities are not only mere things but states of mind: joy, freedom, self-definition, self-esteem . . . Advertising joins with literature in agitating the question of who one is, of what kind of person one should want to be, a choice in which one’s possessions and appearance, one’s tastes, are as important as one’s feelings and behavior.

Kirsch explores how an “age of a new sensibility” driven by “the commodification of spiritual prestige,” reflects an age of “literature’s crisis of confidence.” The triumph of consumerism also weakens the practice of criticism—the two are connected because of the inevitable demand that criticism change in order to survive, to meet the demands of the moment. Trilling anticipated that 35 years ago with a footnote in his book Sincerity and Authenticity:

At the present time art cannot be said to make exigent demands upon the audience. That segment of our culture which is all permeable to contemporary art is wholly permeable by it . . . The audience likes or does not like, is pleased or not pleased—the facility of ‘taste’ has reestablished itself at the center of the experience of art.

Unfortunately, Kirsch doesn’t develop the point, but the centrality of “taste” (I would substitute “experience”) encourages an anemic criticism that simply registers liking or not liking the work at hand: the permeability of the work is taken for granted, releasing the critic from the responsibility of providing the reasoning behind the judgment, discerning and evaluating the intent of the artist, asking the elemental question of whether or not a work was worth creating in the first place. Whether it is mainstream entertainment or niche art, the primary evaluative question is the same: Is there a market for it? The artist either succeeds or not at meeting the expectations of the rapidly collapsing categories of consumer/critic/fan.

In contrast, Trilling viewed novels as an indispensable means to hone the self, the difficulty and complexity of literature as moral/imaginative whetstone challenging contemporary shibboleths and sharpening, through intellectual provocation as well as aesthetic pleasure, the reader’s mind and character. Why Trilling Matters offers a sleek overview of the critic’s approach to literature (focusing on major essays in his collections The Liberal Imagination, The Opposing Self, and Beyond Culture), arguing that an engaged critic is alert to how the fruitful contradictions in novels disrupt cliched thinking, tired ideological polarities, and comfortable reader expectations. One shouldn’t consume art but wrestle with it. But the latter action calls for judgments (throw your opponent or be thrown to the mat), articulate critical responses that invite dialogue with others.

I wish Kirsch had explained more fully what light Trilling’s thought sheds on a culture industry geared toward connecting consumers with the fashionable, artistic pleasures they seek. Instead, Why Trilling Matters deals with how the critic waged an illuminating war on what he believed to be the dangerous energies of Modernism: provocative criticism needed to evaluate, not just praise, Modernism’s celebration of evil as heroism. Trilling’s critical response was to raise a subversive counter-argument, analyzing the strengths of writers (Jane Austen, William Wordsworth, John Keats among others) who dramatized the beauties of everyday existence as well as the enduring value of a moral life. Trilling insists that “writers write for a conscious purpose: to propagate certain ideas about nature, society, and man and to assert the writer’s own claim to power and honor.” At that point in time, it was necessary to cast an ethical light on Yeats and Company’s will-to-spellbind.

But the culture had changed by the 1960s: the will-to-pleasure was culturally ascendant and remains so, buttressed by formidable technological changes. Those who celebrated new forms of artistic rebellion were mistaken—for Trilling, the jig was up: “the highest achievement of the free subversive spirit has been coopted to lend the color of spirituality to the capitalist enterprise.” The decay of meaningful criticism (and literature) is rooted in their complicity with holy commodification: reviewers are absorbed into a cultural economy that is about pointing customers (via thumbs up and down) to the right product, mainstream or niche.

Kirsch ends his book just where he should have dug in: how might Trilling’s stance help revive criticism today, now that subversion is a decorative style? And when reviewers increasingly define their jobs as identifying pleasurable experiences for target audiences? In terms of Trilling’s bedrock ideas, his dependence on the thought of Sigmund Freud (civilization is based on repression) needs to be reexamined given the powerful critiques of the latter’s theories. What did Trilling think of Darwin, a much more relevant thinker? And how would recent attempts to meld evolutionary theory and literary criticism fit in with Trilling’s demand that critics search for “variousness and possibility” in literature?

Also, Kirsch is too concerned with maintaining the “purity” of Trilling’s reputation, which has been questioned lately, particularly in a 1999 essay by Trilling’s son James, who argues that Trilling Sr. unknowingly suffered from attention deficit disorder and that the condition affected his thinking in significant ways. Kirsch doesn’t take up that charge, but he devotes pages to argue that despite evidence to the contrary in Trilling’s journals (which has convinced some), the critic was not a frustrated fiction writer who turned to writing about literature with a sense of bleak defeat. How does that issue bear on why Trilling matters? The critic’s distance from his Jewish background is seen as helping to shape a sharp critical stance (“to stand both inside and outside the modern, to embrace its liberations and mourn its causalities”) from which to critique Modernism, but that raises the issue of why Trilling never examined the literature of the Holocaust. And that, like Edmund Wilson, he pretty well shied away in the latter part of his career from reviewing contemporary novels.

Kirsch wants to position Trilling as an unspoiled cultural hero. Frankly, evidence of his weaknesses only strengthen my admiration for Trilling’s accomplishments as a literary critic and thinker—he was engaged in the hard struggle of shaping his self, guided by a demanding vision of his intellectual vocation. Where I would argue with Krisch’s attempt to make Trilling a model is that he is far too eager to see his subject through the English prism of Matthew Arnold, a critic Trilling respected and wrote a book about. The approach isolates Trilling from a vital American tradition of literary criticism that could use all the reinforcement it can get today:

In fact, the best way to describe Trilling’s uniqueness as a critic is to say that he was always less concerned with writers than readers, less interested in the way novels work than in the way we put them to work in our own lives.

Contrary to Krisch’s claim, this emphasis on literary criticism examining “how we put novels to work” is not unique—it has rich anticipations in the journalistic criticism (and polemics) of Edgar Allan Poe, H. L. Mencken, and Henry James, incisive reviewers who also realized that making judgments (aesthetic and moral) is an essential part of our lives, a primal instinct put into action, most often relatively thoughtlessly, countless times each day. They also saw, like Trilling, that criticism demands the courage to make strong counter arguments, to dabble in dialectical readings, to articulate unpopular critical verdicts in a culture whose egalitarian, commercial, and polarized ideological energies leave little room for discerning independent standards.

The essential task of the critic is not to like or dislike the arts or to push bromides, such as to celebrate the “power of reading.” Despite some troublesome modifications, Trilling carries on the mission of Poe and James: he articulates the value of the serious act of judgment in a culture hostile to it. By making us more aware of “the way we put them [novels] to work in our lives,” he makes us more self-conscious about how we judge everything else around us, encouraging deeper, more substantial thought about why we find certain books, politicians, fashions, technologies, and ideas to be good or bad. Trilling matters because, through the exercise of literary criticism, he shows how developing our powers of discrimination strengthens individuality and contributes to the health of the culture. The best criticism exemplifies a subversion that stays subversive.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Adam Kirsch, American criticism, Lionel Trilling, Literary criticism, arts-criticism, criticism

bill,

hi.

you allude to the piece in (the american scholar, 1999) in which james trilling revisits his fraught memories of his father and concludes: “my father’s worst problem was not neurosis, it was a neurological condition, attention deficit disorder.” james adds, of both his parents (lionel and diana) that: “they disliked the idea that mental states can have physical causes: it took individual behavior out of the control of the individual.”

further: add is a medical problem, not a metaphysical one. . . . knowledge of the disorder would have helped my father, just as it helped me years later. now that he is beyond help, he is also beyond proof. the question of whether he had add has become both academic and technically insoluble, and there is always a risk of vulgarity in diagnosing the famous dead.

james trilling’s piece is telling and worth reading, even if you suspend final belief in the diagnosis. it was written at a time when our culture was finally and definitively shrugging off freud, with whom the trillings were so enthralled, and tilting toward neurology and neuroscience. i don’t think either elder trilling wd have liked olver sacks supplanting sigmund freud as our premier diagnostician. james trilling becomes self-aware in that shift.

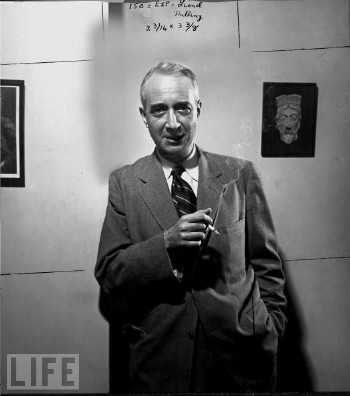

i attended lectures given by and small group sessions presided over by lionel trilling at columbia college in the ’60s. in the small group he asked if any of us had been psychoanalyzed, leaving the distinct impression — as he looked down a nose that ended at his nostrils but originated back in the prose of coleridge & arnold— that if not, we were, not to put too fine a point on it, cultural cockroaches.

i never crawled all the way up that proboscis, & am ready to admit regret that i failed to summit.

then, of course, there was the war in vietnam, the decisive dividing line for people of my age, which, given his shattering experience of cold war polarizations, lionel trilling cd not bring himself to oppose.

i wasn’t psychoanalyzed & cd be drafted into that war. (remember when we didn’t have a volunteer army?) thus my unfortunate lack of connection to lionel trilling.

but, to return to james trilling: what he says about his father having adhd cannot taint lionel trilling’s work & worth — any more than the likelihood that van gogh was epileptic diminishes his visual art or the certainly that dostoevsky was epileptic drains the meaning out of prose.

let me put it this way: these days most everyone deals with neurology/neuroscience. a piece in today’s ny times — http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/01/health/policy/fda-is-finding-attention-drugs-in-short-supply.html?hp — details a shortage in pertinent drugs.

it is only critics, dealing with higher things, who have yet to assimilate the change.

my regards to james trilling.

As a writer, I have to agree with Goethe: “Grau ist alle Theorie . . . und grün des Lebens goldner Baum.”

Theory is gray, but life’s golden tree is ever green. The truly great critics are the ones that break through to the green beneath the gray.

Art that gives pleasure–and praising it for that–is nothing to sneeze at (even with the long nose of Lionel Trilling, as Harvey has it). Part of the instinct to write about art is the desire to share the pleasure with others, not necessarily to sell books or CDs or tickets. I think it depends on what you’re calling pleasure. For me, as for Trilling, putting novels, or any art “to work” in understanding ourselves, our world, our time, is the key to pleasures worth sharing. Thanks for another excellent piece on the whys and why nots of criticism.

I agree with Harvey. If Trilling had ADD it does not undercut his value as a critic — but there were those who reacted to James Trilling’s piece by charging the son with opportunism and character assassination. Kirsch does not deal with that debate, but worries about what some consider to be demeaning insinuations (based on journal entries) that Trilling was a disappointed artist and frustrated critic. Kirsch responds that the latter’s limitations as a creative writer made him a better thinker about literature. I see his point, but I would be more convinced if Kirsch had done a sharper job connecting Trilling to the tradition of American literary criticism represented by James and Poe, who were successful creative writers and critics.

As for pleasure, the point is how you define the joy that art gives. For Trilling (as for Poe and James), literature’s pleasure is connected with difficulty — the reader’s understanding is tested, and accepting that challenge (wrestling with it) combines pleasure with the growth of the mind. Consumerism in the arts is about getting what you pay for — meeting expectations shaped by advertising.

Regarding the Goethe quotation, I would say that critics discriminate, through reasoned judgment, between the green and the gray. Too many of our cultural commentators see the arts through green-colored glasses.

i’m sure i’ll get no argument about this but it’s worth saying that there is no contradiction between criticism & exhilarating writing. i suppose right now i’m thinking pauline kael & susan sontag. there are so many others. & if you include critical works by, say, walter benjamin (on kafka or leskov, for example), it’s clear criticism has no boundaries: it is literature & philosophy along with being criticism. (philosophy, these days, is often best expressed as criticism.)

No argument here with admiring the flexibility and creative restlessness of arts criticism, though when you mention Kael you raise the issue of what happens when sheer exhilaration pushes rational analysis off the cliff, to the detriment of judgment. Somewhere, somehow, criticism has to be more than simply the expression of subjective taste that can’t be discussed only dictated, an opinion rather than an explanation — i.e. I don’t like the color red — this movie uses lots of red — the movie is no good.