Short Fuse Review/Commentary: Steve Jobs and the Digital Acid Trip

No doubt too much can be made out of Steve Jobs’s tripped-out youth, but also, too little. Jobs himself said, “Definitely, taking LSD is one of the most important things in my life.” He never recanted when it came to psychedelics or disowned their influence.

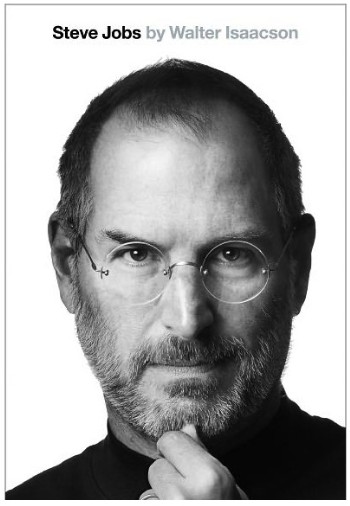

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson. Simon and Schuster, 656 pages, $35.

By Harvey Blume.

Steve Jobs: February 24, 1955 – October 5, 2011

Given the attention Walter Isaacson’s biography has deservedly received from media—reviews, excerpts, Isaacson appearing on talk shows—you are likely familiar with many of Steve Jobs’s quirks, oddities, and peccadilloes. You may know Jobs drove around without license plates and routinely parked in handicapped spaces, that he went on strict fruit and vegetable diets, that he studied Zen, and that, as a youth, he cultivated an intense persona one friend from those days described as “oscillating between charismatic and creepy.”

You may also have heard that when he was 16, he and his best buddy, Steve Wozniak [aka Woz], an engineering mastermind with a madcap streak, put together what they called a Blue Box that could generate the AT&T tones needed to dial any number they liked. They placed one such call to the Vatican, with Woz posing as Henry Kissinger. Woz said, “Ve are at de summit meeting in Moscow, and ve need to talk to de pope.” A bishop on the other end eventually determined that the call was not coming from any Moscow summit but from a pay phone, perhaps in California.

That particular stunt, as it happened, did not just leave the pranksters laughing, much as the two Steves of Silicon Valley enjoyed their pranks. Jobs and Woz made a small business out of the Blue Boxes, putting 100 units together—each assembled out of $40 in parts—and selling them for $150 each. Jobs believed that experience laid the foundation for his whole career. “If it hadn’t been for the Blue Boxes, there wouldn’t have been an Apple,” Isaacson quotes him saying. “Woz and I learned to work together and we gained the confidence that we could solve technical problems and actually put something into production.” Woz, who would co-found Apple with Jobs, felt the same. “You cannot believe how much confidence that gave us,” he recalled. “It gave us a taste of what we could do.”

Any number of such anecdotes spill out of the Isaacson’s bio. The author does not neglect the humorous side of the Jobs story. Here, however, is a tale that seems so out of any context it has not made the rounds.

In 1985, Jobs went to Moscow to promote technology. No, when given a chance, he didn’t compare Bill Gates to Joseph Stalin, though who’s to say the thought didn’t cross his mind? After all, Apple’s famed ad—shot by Ridley Scott, coming off the success of Blade Runner—shown in 1984 at Super Bowl XVIII, touted the soon-to-be unveiled Macintosh as nothing less than the force to topple Big Brother (aka IBM). (As the ad’s announcer put it, “On January 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’” )

What Jobs did do, in Moscow, however, was reveal a previously unspoken—and never repeated—enthusiasm for Leon Trotsky. This did not endear him to his Soviet hosts. “At one point,” writes Isaacson, “the KGB agent assigned to him suggested he tone down his fervor,” bluntly telling Jobs, “You don’t want to talk about Trotsky.”

Jobs had many talents but toning down fervor was not among them. When he met with computer students, he “began his speech by praising Trotsky.”

Why wax on about Trotsky in the most inhospitable place on earth to do so? For that very reason, perhaps. To put it another way, being Jobs, how could he not?

Aside from the praise the Isaacson bio has garnered, it has also occasioned some strange misreading. Malcolm Gladwell, while calling the book “enthralling” (The New Yorker, November 14, 2011), refuses to credit Isaacson’s assertion that Jobs was a visionary. Instead, he cites a number of obscure but topnotch English and Scottish engineers who fine-tuned elements of the machinery that gave England its edge in the industrial revolution: Gladwell categorizes them as “tweakers” and lumps Jobs in with them. Jobs was a tweaker too.

However mightily they tweaked, posterity seems to have lost track of them, whereas it’s hard to imagine Jobs being dropped from pride of place in the annals, at least, of computer history. And there’s the not inconsiderable fact that Jobs did not succeed by virtue of superior engineering chops: when he ran Apple, the aesthetic of design, as he refined it, was dictated to the engineers, who often squawked, said it was impossible, then engineered the impossible. What needs a good stiff tweak here is Gladwell’s pedanticism, his inability to grasp the many-sided personality—designer, futurist, marketer, artist, media-maven, game changer, celebrity, and, oh yes, pain in the ass—that emerges from Isaacson’s pages.

Nor does Gladwell get that when it comes to computers, we are all end users. The “clean sheet of paper” that is all the equipment Gladwell thinks a real visionary needs as he “re-imagines” the world is simply not to be found in a sequence that includes Boolean algebra, binary arithmetic, Turing machines, Von Neumann bottlenecks, quantum mechanics, transistors, integrated circuits, mainframes, minis, personal computers, DARPA, Multix, Unix, the Internet, the World Wide Web, C++, the iPhone, and Google.

Was Jobs a tweaker? If Thomas Edison was, when he tweaked electrons or Ted Williams when he hit .406. Indeed, couldn’t it be argued that Hemingway but tweaked the novel and that, at bottom, Shakespeare only tweaked tragedy, comedy, and, when in the mood, the sonnet? Isaac Newton said, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Was he saying that he had tweaked thermodynamics?

Not that I mean to compare Jobs’s accomplishments to those of a Shakespeare or Newton—or Einstein, the subject of a previous bio by Isaacson. Jobs is not in that company, nor ever dreamed that he was. It matters, though, that he was capable of being inspired by their kind. J. Robert Oppenheimer, for example, was a role model. “I read about the type of people he sought for the atom bomb project. I wasn’t nearly as good as he was, but that’s what I aspired to do [for Apple].” Yes, it’s jarring to compare the Manhattan Project to the graphical user interface, but also indicative of Jobs’s gift for defying boundaries, slipping between contexts and intuiting commonality. Jobs loved Bauhaus design, Kyoto gardens, and Tiffany Glass—taking the Macintosh team with him to a Tiffany retrospective to prove you could make “great art that could be mass-produced”—much as he loved the serif and sans serif typefaces that the bit-mapped Macintosh brought to home computers. Neither Jobs’s sensibility nor his kind of ambition can be shoehorned, without procrustean reduction, into Gladwell’s rubric of “tweaker.”

Another way of accounting for Steve Jobs’s success is humorously summarized and dispatched by Tom McNichol in his “Be a Jerk: The Worst Business Lesson From the Steve Jobs Biography” (the Atlantic, December, 2011). McNichol suggests that the next generation of business books will sport titles like,The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Assholes and The One-Minute Asshole. He quotes research showing that the new big idea among “a disconcerting number of Silicon Valley leaders” is the conviction that “Steve Jobs was living proof that being an asshole boss was integral to building a great company.” McNichol does not subscribe to this view. “The fact is, Steve Jobs didn’t succeed because he was an asshole,” he writes. “He succeeded because he was Steve Jobs.”

Still, how to account for being Steve Jobs? Isaacson’s multi-threaded book does not settle for any one explanation; it allows for many, including some that are highly critical of Jobs. Throughout his career, Jobs ordained that Apple make closed machines, at one point devising “special tools so that the Macintosh case could not be opened with a regular screwdriver.” Keeping the literal lid on, much as Jobs insisted on it, was secondary to ensuring a perfect fit between Apple’s propriety operating system and its hardware. There is no doubt that in the end this gave Apple the edge in the design of the desktop computer, the laptop, and mobile devices, forcing others in the field, again and again, to play catch-up. But there were times when it seemed Apple might perfect itself out of business. Bill Gates got in a good one against Jobs when he quipped, “His product comes with an interesting feature called incompatibility.”

Confronted with Jobs’s famed temper, Gates proved to be a cool counterpuncher. As is well known, Jobs got the idea for a mouse-driven graphic interface from a visit to a Xerox lab, where these innovations were in the works. Nor did he deny it, recalling, “It was like a veil being lifted from my eyes. I could see what the future of computing was destined to be.” When Microsoft decided to launch Windows, its own GUI—which for many years, to Mac users, looked like a decayed version of the Apple OS, like Apple with Hansen’s disease—Jobs was outraged, screaming at Gates in a Cupertino showdown: “I trusted you and now you’re stealing from us!” Blinking a few times, Gates, in his “squeaky voice,” calmly replied: “Well Steve, I think there’s more than one way of looking at it. I think it’s more like we both had this rich neighbor named Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set and found out that you had already stolen it.”

Score one for Gates. But his riposte leaves room for doubt. It’s easy to imagine Gates breaking into Xerox and ignoring the TV or thinking, if it were on, cute—those icons, that mouse—but what does this have to do with computing? The veil that fell at once from Jobs’s eyes might have remained over Gates’s indefinitely—or precisely until the Macintosh eliminated all doubt about the future of computing. Here, I take my cue from Jobs, who said of Gates, “He’d be a broader guy if he had dropped acid once.” I’m suggesting that if Jobs is to be shoehorned, he might as well be shoehorned into a tab of LSD.

No doubt too much can be made out of Jobs’s tripped-out youth, but also, too little. Jobs himself said, “Definitely, taking LSD is one of the most important things in my life.” He never recanted when it came to psychedelics or disowned their influence. In 1980, after Apple had gone public, he spoke to a class of Stanford business students and after submitting to a dull and predictable barrage of questions about the worth of Apple stocks, he asked, “How many of you are virgins? How many of you have taken LSD?” (It was a Steve Jobs version of Jimmy Hendrix singing “Are you experienced? Not necessarily stoned, but beautiful.”)

It wasn’t just isolated acid trips that shaped Jobs; it was the unique set and setting afforded by the Bay area culture of his youth. Isaacson writes, “In San Francisco and the Santa Clara Valley . . . There was a hacker subculture—filled with wire heads, phreakers, cyberpunks . . . There were quasi-academic groups doing studies on the effects of LSD; participants included Doug Engelbart . . . who later helped develop the computer mouse and graphical user interfaces, and Ken Kesey, who celebrated the drug with music-and-light shows featuring a house band that became the Grateful Dead.”

Jobs never failed to credit the formative, boundary buckling power of that culture. “There was something going on here,” he told Isaacson. “The best music came from here—the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Joan Baez, Janis Joplin—and so did the integrated circuit.”

LSD and other psychedelics excite, magnify, and sometimes derange the senses. They can make sound visible—the most common synesthetic effect—and colors audible. The veil was ready to fall from Jobs’s eyes when he visited Xerox: here was a computer built on graphics—monochrome at first but not for long, the ability to produce thousands of hues arriving soon enough. Here, with the mouse, was a way of interacting with that computer physically rather than alphabetically, by tortuously typing easily misspelled chains of commands (often, back then, in heartless, green characters on a joyless, black screen). It’s not absurd to see Jobs’s whole career—from the underpowered, overpriced, and completely revolutionary Macintosh on through Pixar, iTunes, and the iPhone—as an effort to ground expanded senses in technology. And then there are his product announcements. Isaacson writes, “With the launch of the original Macintosh in 1984, Jobs had created a new kind of theater: the product debut as an epochal event.” It’s not too much of a stretch to call these the Cupertino correlate to Fillmore West light show. Bono once complimented Jobs’s devotion to design by saying, “The job of art is to chase ugliness away.” (Bono also called Jobs Apple’s “lead singer.”)

Would Gates, breaking into Xerox, know what was worth stealing? Quite possibly, given lack of psychedelic/countercultural coaching, nope.

Jobs’s life is not altogether triumphant. For one thing, he died young, at 56. And his death leaves much to dwell on. Despite urging from family, he put off surgery on his pancreatic cancer for nine months. (His body was a Macintosh for which no one, in his view, had the approved screwdriver.) In the interim, he saw psychics, masseuses, herbalists, acupuncturists. He fasted and drank carrot juice.

Would surgery, shortly after the diagnosis of cancer, have saved him? Doctors debate this, some saying it was the type of malignancy that would have already have spread to the liver and beyond, others arguing it was an “indolent” cancer, susceptible to surgical intervention. It’s notable that none of the psychics, acupuncturists, or herbalists Jobs consulted are on record expressing comparable doubts about themselves or disagreements with each other. Did any of them say, were any capable of saying, look, Steve, we think you have a better shot with surgery. Did they heal/help him? Or did they just help him die?

Then there are the last words of Steve Jobs. Einstein, dying, asked for his pencil, as if in his final moments the Old One would vouchsafe the equation he had been seeking for decades, the one that would undo quantum mechanics. Richard Feynman said, “This dying is boring.”

Make what you will of it, but Jobs reportedly said, “Wow.”

Splendid review, Harvey! The LSD connection was obvious to many of us, and good for Isaacson to report it, and great for you to underline it. I will add only that in addition to sense-enhancement, art, and the cultural milieu of the day, acid also could provide specific technical insights if you were looking for solutions to a problem. I’m not sure it’s quite the same now: I last took some fifteen or so years ago, and the terrain looked too familiar. Maybe it wasn’t strong enough 🙂 Wow! indeed. Andrei

Always good to hear from you & I’m glad you liked.

I must say, though, when I read “I last took some fifteen or so years ago, and the terrain looked too familiar. Maybe it wasn’t strong enough,” I think maybe the doors of perception get creaky in the course of time.

Then I allow myself to imagine what it would have been like to trip with Steve Jobs—or even, had he dared, Bill Gates.

The doors of perception clanged shut (for the first time) on March 11, 1973. After that, you needed a crowbar. Andrei

Andrei, what catastrophe corresponds to 3/11/73?

Sue Halpern, in her take on Steve Jobs in the current nyrb, says something against which I will not defend him. She talks, as others have, about Apple’s oppressive policies in its Chinese factory.

Were/are they worse than other practices in Chinese factories? Perhaps not. Most likely not. The Chinese workers suffer and are lately, in some cases, rising up.

But that is no legitimate defense of Apple’s factory policies.

I would only ask what Jobs would have done, had he been healthy enough, long enough, to confront that situation. I don’t know. Neither does Sue Halpern.

But she thinks she does.

She’s clearly out to get Steve Jobs.

She writes:

Steve Jobs cried a lot. This is one of the salient facts about his subject that Isaacson reveals, and it is salient not because it shows Jobs’s emotional depth, but because it is an example of his stunted character. Steve Jobs cried when he didn’t get his own way.

I, carefully, read the same Isaacson bio. Yes, Jobs, as attested by Isaacson, cried a lot. Isaacson leaves it open about why. He shows Jobs crying in situations that don’t reduce to his not getting his way. He shows him crying.

Jobs had peculiar drive harshness and also vulnerability.

For Sue Halpern, it’s obviously all about him being “stunted.”

It’s not obvious at all.