Music Review / Commentary: A Dispatch from the Border

Boston Conservatory’s New Music Festival is inspiring a series of critical and speculative commentaries from Fuse Jazz Critic Steve Elman. Here is the first.

Boston Conservatory New Music Festival.

Held annually, The Boston Conservatory New Music Festival is a four-day celebration of music evolution throughout the ages and is dedicated to recognizing exceptional compositions by modern composers. This year the gathering runs from December 1st to the 4th and explores the musical development of the jazz genre. The Festival features works by renowned composers such as Bernard Lang, Edison Denisov, Robert Graettinger, Pierre Hurel, Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, and Gunther Schuller, who will also make a special appearance as music director. The event will include performances by I/O Ensemble, Philipp Stäudlin, George Garzone, John Lockwood, and Bob Gullotti, to name a few, and is free and open to the public.

Held annually, The Boston Conservatory New Music Festival is a four-day celebration of music evolution throughout the ages and is dedicated to recognizing exceptional compositions by modern composers. This year the gathering runs from December 1st to the 4th and explores the musical development of the jazz genre. The Festival features works by renowned composers such as Bernard Lang, Edison Denisov, Robert Graettinger, Pierre Hurel, Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, and Gunther Schuller, who will also make a special appearance as music director. The event will include performances by I/O Ensemble, Philipp Stäudlin, George Garzone, John Lockwood, and Bob Gullotti, to name a few, and is free and open to the public.

By Steve Elman

We persist in inadequate physical metaphors for musical experience and activity. A jazz solo consists of “gestures” or “patterns.” A classical composition has an “arc” or a “landscape.” But consider that light travels in straight lines, but sound bends around corners. Though music is a physical reality (at least for those lucky enough to perceive it that way), it behaves more like fog or lightning than like an object that can be held or described.

This reality is particularly thorny whenever one tries to engage in descriptions of hybrid music, and it is an enduring perplex of the interactions of jazz and classical music.

However you limit the traditions that make up the musical territories (see? can’t avoid the physical) that we call “jazz” and “classical,” the boundaries between them are porous, and from the moment that something like jazz existed, there have been explorers from one discipline more than willing to adventure into the other.

(Caveat: metaphor realignment ahead.) When hybrid works result from such cross-genre mating, the products have usually been like mules, successful in achieving limited goals but disappointing in the robust offspring department.

This may be more a problem of listeners than it is of composers and performers. The marketplace simply has not rewarded these mules with the popularity that might inspire a tradition of hybrid work. Gershwin’s piano concerto, Ravel’s Concerto in G, and the first movement of Peter Lieberson’s 1983 piano concerto all draw a certain amount of inspiration from the jazz tradition, but the concerti of Rachmaninoff and Mozart are still programmed far more often than even the Gershwin, which is as tuneful and appealing as classical music can be. Ellington’s “Black, Brown and Beige” behaves a lot like a symphony, but only the “Come Sunday” theme from it has achieved anything like familiarity. Adam Makowicz’s improvisations on Chopin and Louis Singer’s reworking of Chopin into “Charley’s Prelude” are completely convincing as jazz, but they are very little-known among jazz people. Even Keith Jarrett, the one musician (pace Wynton Marsalis) who could possibly achieve true synthesis, chooses to keep his jazz beret and his classical chapeau on separate pegs.

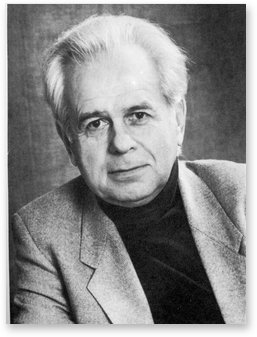

Boston Conservatory’s Eric Hewitt — credit him with boldly showcasing what others have tried with trepidation.

So, after that long-winded intro, I take my hat off to Eric Hewitt of the Boston Conservatory (TBC) for boldly showcasing what others have tried with trepidation. Hewitt is chair of TBC’s woodwind department and the artistic director of this year’s New Music Festival at TBC. The theme statement of the festival (which he presumably approved) puts it right out there: “Jumpin’ into the Future – New Music Evolved from Jazz.”

The Festival consists of four concerts, and each one shows sensitivity to the challenges presented in the assembly of works for an individual concert program and the different kinds of challenges in the conception of a coherent series.

In the first one (unheard by me), called Improvisatoria, TBC faculty pianist Pierre Hurel put 12 of his students onstage to improvise collectively, as they do in his Improvisation Workshops. In the second, Across the Pond, virtuosi of new music performed “classical” pieces that incorporate jazz elements of various kinds (more on this in a moment). In the third, The Fringe interprets four pieces associated with John Coltrane and then improvises collectively as only they can. In the last concert, composer Gunther Schuller conducts a program of mostly-composed music emerging from the jazz tradition, including two of his own pieces for jazz big band, three pieces by Charles Mingus, George Russell’s “Lydian M-1,” and Bob Graettinger’s “Thermopylae” and “City of Glass.”

I heard the Across the Pond program on December 2, and I expect to hear the third and fourth programs as well. This was my first experience in TBC’s renovated theater, designed by Handel Architects, and I wish I could have given the acoustic designer a round of applause. The 300-seat room, re-opened a little more than a year ago, is about 60 years old, but the renovation makes it seem brand new. The sound is warm and clear for unamplified and amplified instruments, the seating is better than comfortable, the sightlines are excellent, the extra-musical facilities (in this case, lighting and image-projection) enhance the experience, and the PA is perfect. The hall staff seemed to have a little trouble deciding how they wanted to use the lights, but the non-human elements worked perfectly. This is a little gem of a space.

Across the Pond concentrated on compositions drawing on the trappings of jazz rather than improvisation, which shouldn’t have been surprising. From the twenties on, “jazz-influenced” classical composers have usually evoked the atmosphere of jazz rather than its essence, and most of the music on this night was solidly in that tradition—we heard instrumental slurs, vocal sounds projected through instruments, trumpet with jazzy mutes, and the trap kit conceived of as a single percussion instrument. The single most obvious “jazz” element was the use of the saxophone itself, which appeared in each piece in a starring or supporting role.

Exception 1: There was some improvisation (more middle-Eastern than jazzy) in Goran Daskalov’s “Macedonian Dance.”

Exception 2: The ghost of Steve Lacy appeared occasionally in Bernhard Lang’s “DW-16: Songbook 1.” Lang uses obsessive repetition for vocal music much in the way that Lacy used it in his instrumental compositions, but, since Lacy’s work was sui generis in jazz (and since he and Lang actually worked together), the repetitive elements in Lang’s work are more a demonstration of like-mindedness than a deliberate borrowing from jazz as a genre.

This is probably not an exception: The solo saxophone passage in the second movement of Edison Denisov’s 1970 “Sonate for Alto Saxophone and Piano” evoked Anthony Braxton’s 1969 LP “For Alto,” but the resemblance there surely was coincidental, since Braxton was almost unknown in 1969 and the LP didn’t actually appear in stores until late 1970.

Overwhelmingly, this was a case of new music, straight, no chaser, performed flawlessly and received enthusiastically.

Daskalov’s “Macedonian Dance” was the most extroverted and least traditional of the pieces, deliberately modal and evocative of Balkan music (that is, music descended from the Ottoman domination of the Balkans). The composer played the saxophone part exuberantly, and he received impeccable support from Nate Tucker, playing the dumbek.

Siberian-born composer Edison Denisov (1929–1996) received two great gifts: the programming of two similar works written 34 years apart and the unbounded virtuosity of German saxophonist Philipp Stäudlin. Both of Denisov’s sonatas for alto saxophone call for quarter-tones and machine-gun arpeggiation. The 1994 “Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Cello” also incorporates extensive use of circular breathing and gossamer, super-pianissimo articulation. Stäudlin didn’t just make all of the technical challenges seem effortless; he turned them into deeply expressive music. This is not to minimize the virtuosity of cellist David Russell or pianist Yoko Hagino, who both rose to the challenges of their parts beautifully, but the spotlight in these pieces is usually on the saxophonist.

Andy Vores’s “Weegee” left me with some of the strongest positive impressions. Vores was born in Wales (“across the pond” indeed), but he’s now a thoroughgoing Bostonian. He came to the city in 1989 in a residency funded by the composers’ consortium NuClassix, and he has only been away for two of the intervening years. Since 2001, he’s been chair of composition, music theory and history at TBC. His music is refreshingly direct and forceful. I identify him as a spiritual brother of other NuClassix composers, many of the Composers in Red Sneakers, and other members of cooperatives following in their wake, composers coming up in the 1980s for whom the quality and art-value of jazz was a given rather than something that had to be earned.

“Weegee” is a suite of 10 miniatures inspired by the work of the noir photographer Arthur Fellig, whose black-and-white crime and street images raised photojournalism to the level of art in the 1930s and 1940s. In addition to displaying a keen eye for dramatic composition, Weegee’s work had something of the passionate dispassion of Edward Hopper; the underworld he photographed was intimate and alien at the same time. Vores calls for the images to be projected behind the ensemble, and he chose a somewhat distorted perspective so that they appeared as trapezoids rather than rectangles.

Vores directly referred to jazz in “At a Jazz Club in Harlem” with what he calls “ersatz bebop,” and he glanced at it again in “Dead Man in a Restaurant” with some voicings that suggested Henry Mancini’s TV scores, but these passing references didn’t distort the overall drama of the music. The scoring, especially for percussionist Matthew Sharrock, was consistently evocative. Explosions from the traps suggested off-camera violence; lugubrious mutterings from bass clarinet and cello were ship noises and commentary from bystanders; glittering glockenspiel effects were aural sparks, snow, fire hydrant spray; bowed vibraphone tiles added ethereal shimmer to solitude; a joky cakewalk brought out the parody in an Easter parade in Harlem.

If only such forthrightness were part of Bernhard Lang’s vocabulary. Lang’s “DW-16: Songbook 1” is a setting of texts by Bob Dylan, English singer-songwriter Peter Hammill, Dieter Sperl, Robert Creeley, and the German rock band Amon Düül II. All of these texts are subject to manipulation by the composer, but the pop-music lyrics are atomized into phonemes using a computer program and then built into repetitive sequences. This approach has the great advantage of allowing the listener the chance to examine and appreciate the same musical gesture over and over and incidentally to admire the technique of the musicians performing it. But it neither illuminates nor illustrates the text. For me, only the setting of Sperl’s “Count 2 4” enriched the words, and in that case, I thought the setting benefited from being closer in spirit to a traditional lied. In the case of the one text I know well, Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” Lang transforms it from Desolation Row redux to a rather tedious philosophical parable. The setting concludes with the line “Life is but a joke.” In the original song, Dylan buries that direct statement in the middle of the lyric, concluding with more indefinite and ominous words that Lang omits: “Two riders were approaching, and the wind began to howl.”

The content of the music left me unmoved, but I found the performance of it thrilling. Two members of the I/O Ensemble, described in the program and on the Williams website as “the house band” for contemporary performance at Williams College, supported Philipp Stäudlin and soprano Aliana de la Guardia, who had the primary roles. Brian Simalchik provided an important foundation for it all with piano and electric keyboards. Matthew Gold, who directs I/O, expertly managed the percussion arsenal, a combination of trap kit, gongs, vibraphone, wooden blocks, and little instruments, drifting from arrhythmic color to near-funk.

These were song settings, so the singer was expected to be the star, and de la Guardia was stellar. Her natural sound is lovely, as clear and powerful as grain alcohol. In addition, her control of “in the margin” techniques is super—Sprechstimme, inhaled singing, dramatic recitation, extremes of range and volume, articulation of tiny shards of words, and (since this a work for amplified singer and instruments) expert microphone control. She also put some splash into the performance, providing some gentle hip sway in the Dylan and Amon Düül settings that added much-needed irony, and for a minute or so pacing the stage with her mic, freed from the score.

Was any of this “evolved from jazz”? Perhaps a bit, but only a bit. Was it worth hearing? Without a doubt.

More to come in the days ahead.