Classical Music Review: Boston Symphony Orchestra/Ludovic Morlot at Symphony Hall

While I’m not necessarily sold on this particular interpretation of Mahler Symphony no. 1, it was a thoughtful reading led with conviction; conductor Ludovic Morlot drew a committed performance from the BSO, and that counts for something.

Boston Symphony Orchestra/Ludovic Morlot. At Symphony Hall, Boston, MA, November 26.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Ludovic Morlot returned for his second week of subscription concerts this season to lead an all-symphonic program.

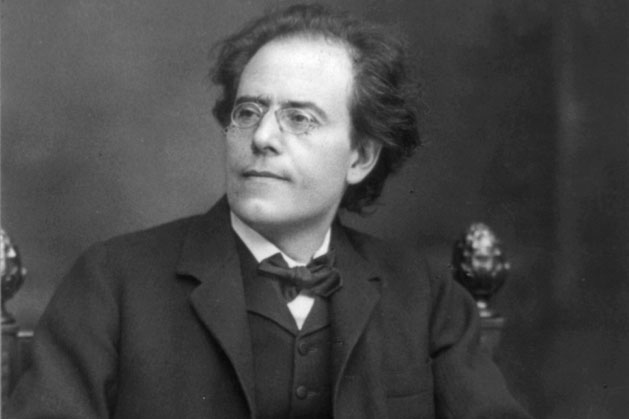

“A symphony must be like the world. It must contain everything,” commented Gustav Mahler to Jean Sibelius at their only meeting in the summer of 1907. This weekend the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) put Mahler’s famous sentiment to the test in an all-symphonic program featuring two symphonies and a suite from one very symphonic ballet. Ludovic Morlot returned for his second week of subscription concerts this season to lead the orchestra in works by John Harbison, Maurice Ravel, and Gustav Mahler.

The first work on the program was John Harbison’s Symphony no. 4. Mr. Harbison, who has a relationship with the BSO that goes back nearly 30 years, is the latest in a line of Cambridge-based composers the orchestra has recently championed (Peter Lieberson and Leon Kirchner come to mind as well), and his symphonies have been at the center of a BSO survey begun last season under the direction of James Levine. Written for the Seattle Symphony in 2003, his Symphony no. 4 falls into five movements, with a Scherzo as its centerpiece, a formal model similar to one used by Mahler in three of his symphonies.

So, given that its architecture alludes to Mahler, does the musical content of Mr. Harbison’s Symphony embrace the world on Mahler’s terms? At times it certainly seems to try. In a note on the work, Mr. Harbison observes that while he was fulfilling the commission for this piece, he was working his way out of the compositional influence of his opera The Great Gatsby, which had premiered in 1999 and was less than four years behind him. Accordingly, there are moments in the Symphony (particularly its first and third movements) where jazz-tinged sonorities and rhythms make themselves heard, and these result in some of the work’s more memorable sections.

The Symphony’s fourth movement, “Threnody,” is to my ears the most effective of the five. Mr. Harbison’s note indicates that his writing this movement was in response to the “breath of mortality” touching someone very close to him; this personal focus gave the music an immediacy that is lacking elsewhere.

Much of the piece alternates between repetitive, rhythmic figures; glowering, dissonant harmonies; and unremarkable melodic content. Yes, it’s “tonal” after the late-20th-century manner, and its form is relatively easy to follow, but, aside from the fourth movement, there isn’t much music that sticks in the memory. The score isn’t exactly derivative—though it’s not difficult to hear the influences of Stravinsky, Mahler, and Bolcom, among others—but it doesn’t leave a strong impression.

Part of the problem, I think, is its harmonic language. In my experience, extended samplings of basically tonal material combined with regularly dissonant harmonizations generate an affect of ill-definition. Ironically, I find myself preferring the harmonic complexity of someone like Elliott Carter (particularly so after the scintillating performance this ensemble gave of Mr. Carter’s Flute Concerto last week) or Schoenberg to “accessible,” blandly tonal offerings. So it was with this Symphony.

Regardless of my musical quibbles, the BSO and Mr. Morlot gave a technically solid performance of the work. Mr. Harbison’s orchestrations are never short of expert and colorful—the numerous instrumental solos in the first two movements, especially, demonstrate a keen ear for fascinating timbral combinations—and the orchestra dispatched them with clarity and agility.

Following Mr. Harbison’s Symphony, Mr. Morlot led a sumptuous performance of the Suite no. 2 from Ravel’s ballet Daphnis et Chloé. Ravel wrote the ballet on a commission from Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe, completing it a century ago, though its stage premiere didn’t occur until 1912 (the year between Petrushka and The Rite of Spring). The Suite no. 2 has been a mainstay of the BSO’s repertoire since Karl Muck first led a performance of it in Symphony Hall in 1917.

The first of the Suite’s three movements, “Daybreak,” depicts nature coming to life in vivid instrumental colors. Mr. Morlot drew a stunningly clear account of this music from the large orchestral forces; there was an expansive delicacy to the orchestra’s playing that was remarkably fine-spun while never becoming overwhelming.

One of last week’s soloists, principal flute Elizabeth Rowe, was again in the spotlight in the Suite’s second movement, “Pantomime.” This is music that in the ballet depicts a reenactment of the story of Pan and Syrinx, and Ms. Rowe’s accounts of her solos were full-bodied and warmly shaped.

The final “Danse general” features Ravel at his most exuberant. Though the orchestra creates tremendous walls of sound in this finale, there is much intricate activity between the individual parts, and Mr. Morlot drew out these strands in a truly exciting reading of the score. There were too many superbly executed woodwind solos in this movement to mention individual players; suffice it to say, the BSO was wholly in its element—here (and throughout the Suite) they played at their inspired best.

Mahler’s Symphony no. 1, which formed the second half of the program, is a score that certainly bears out its composer’s earlier statement, developing a simple falling motive of humble, primordial origins into a triumphant paean while exploring every conceivable musical and emotional iteration along the way. It’s always interesting to hear what different conductors bring to their Mahler performances. I’m not familiar with any of Mr. Morlot’s previous Mahler interpretations, but this one I found highly singular and unexpectedly French.

In Mr. Morlot’s interpretation on Saturday, the Symphony’s opening movement was taken at a very leisurely pace that at times felt quite deliberate. Mahler’s hard edges—and this isn’t the hardest edged of his symphonies—were softened, sometimes to fine effect, other times simply sounding like strangely blunted Mahler. Though Mr. Morlot achieved some extraordinarily soft dynamic shadings from the ensemble, often these quieter moments lost whatever little sense of momentum that had been present earlier.

The second movement fared rather better and was played with full, rustic character. I do wish Mr. Morlot had observed the tempo shift Mahler wrote into the fifth measure, though that’s a subtlety that has been ignored by any number of more senior baton-wielders. The movement’s Trio was given a gentle reading and formed a very nice contrast to the foot-stomping rhythms of the outer sections.

Mr. Morlot’s slower pacing was most successful in the third movement, where he brought out the many strange and wonderful colors of Mahler’s orchestration. Principal bass Edwin Barker gave a finely shaped account of his opening solo, and the imitation-Klezmer band swung with great character. Remarkable, too, was the ethereal playing of strings and harp where Mahler quoted his song “Die zwei blauen Augen” at midpoint in the movement—the effect was hypnotic.

In the finale, tempos were again on the slower side, and, curiously, Mr. Morlot seemed reluctant to explore the movement’s more expansive moments. Like some of Pierre Boulez’s Mahler performances, Mr. Morlot led a very straightforward reading of the movement; its climactic moments came more as sudden cloudbursts than as crests of inexorable waves of energy and emotion.

While I’m not necessarily sold on this particular interpretation of Mahler 1, it was a thoughtful reading led with conviction; Mr. Morlot drew a committed performance from the BSO, and that counts for something. Perhaps when they take this work on tour with them to California next month the interpretation will truly gel; regardless, West Coast audiences are in for a treat.