Jazz Concert Review: Two Paths Converge Again — Sheila Jordan and Steve Kuhn

The Steve Kuhn/Sheila Jordan partnership has been one of the luckiest things ever to happen to either of them and for us as listeners.

By Steve Elman

Singer Sheila Jordan — she radiates enough optimism and joie de vivre in ninety minutes’ worth of music to counteract a year’s worth of bitterness.

For all the vaunted style of AMC’s Mad Men, the series lacks imagination when it tries to fill out the extra-agency lives of Sterling Cooper’s female employees. Peggy Olson is pathetic and confused when she’s not striving to be the equal of the male account execs; the only dignity Joan Holloway Harris has is in the exercise of her power as office manager; and the rest of the officewomen, like Don Draper’s secretary Megan Calvet, are near-ciphers.

What the series needs is a character based on Sheila Jordan. Now here’s a backstory that any of the Mad Women would kill to have: born to a single mother, raised in the cinders of coal miners’ West Virginia, blessed with a native talent for singing nurtured in a crowd of bebop-mad teens in Detroit, dumbstruck by Charlie Parker (who praised her “million-dollar ears” when she got to New York), married briefly to occasional Parker pianist Duke Jordan, divorced from Duke with a daughter to raise, championed by George Russell and consequently given a lavishly-praised recording debut, frustrated by lack of work as a musician and the need to care for her child, and finally resigned to office work at a big ad firm for a regular paycheck, with her singing held to an intermittent sideline.

You can see how she might be introduced in the series as a woman with a chip on her shoulder, someone to provide real-world contrast to the sterility of the suits, tossed a crumb or two by the agency to provide music for its TV commercials, still occasionally getting the chance to do a real jazz club date. You can almost see the scene where the boys from the office go to the Village for one of her gigs to laugh behind their hands, the camera holding on their stunned faces as they look up from their booze, suddenly mute at what this chick could do if given half a chance.

That’d be the dark side, the cable side, of the character’s life. Network TV would demand a happy ending for such a person, but video’s most Pollyannish producers could never sell the Cinderella frontstory that is Sheila Jordan’s real bio: keeping the faith, rebuilding that singing career in her late forties, making enough money (finally!) as a working musician to quit her day job, and achieving such stature in the following years that she has ended up more famous and respected in the 2010s than any of those buttondowns she used to work for.

Sometimes, as Mose Allison observed, “If you live, your time will come.” That’s a lyric Sheila Jordan could sing today without a wink of irony. When she performs, as she did in Cambridge at the Regattabar on November 17, she radiates enough optimism and joie de vivre in 90 minutes’ worth of music to counteract a year’s measure of suited bitterness.

When Jordan sings, she frequently acknowledges (and often sings directly to) acquaintances in the audience. She effectively erases the usual distance between performer and audience, turning her shows into casual evenings among friends. She interprets songs with deep feeling but only as extensions of her own life (for example, when she sang “Lady Be Good,” remembering Ella Fitzgerald’s version, she inserted the word “luck” into the song so that it became an appeal to Lady Luck, not to another woman.) She scats like a true instrumentalist, using wordless phrases to build real solos with beginnings, middles, and ends. Best of all, she always seems grateful to be singing and grateful to be alive.

A Jordan date is never a star turn. I remember seeing her in 2009 at the London Jazz Festival, accompanied by a trio led by Brian Kellock, a well-respected jazzman from Scotland who’s hardly a household name, even in Europe. On that afternoon, she was as gracious to Kellock and as generous in giving him solo space as if he were her old friend and frequent partner Steve Kuhn.

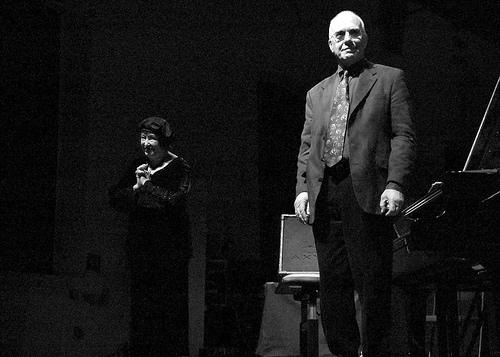

That was a fine performance, if not Jordan at her peak. For that you need to hear her with Kuhn at the piano, where he was on November 17. He was as sphinx-like as Jordan was effusive, providing the gravity to keep her balloon at exactly the right altitude and punctuating the music only rarely with a half-smile or a raised eyebrow.

Better listeners than I confirm Kuhn’s mastery and eminence as a musician. In this case, I defer to John Harbison, one of the greatest of contemporary, classical composers. After Kuhn and Jordan finished their set, Harbison came up to the stand with all the other well-wishers, and Kuhn’s face lit up with delighted recognition. Then the two men embraced, and that moment said everything that needs to be said about the esteem Kuhn has among his peers.

Thirty years of listening have given me a lot to say about Steve Kuhn but few adequate words to do so. He chose a winding path that proved an interesting alternative to those of his predecessor Bill Evans and his contemporary McCoy Tyner, both of whom remain towering influences but in some ways limited by the beautiful stylistic boxes they constructed. He has a notably individualistic, almost European, touch on the keyboard. As a soloist and improviser, he sounds like himself without sounding like he is imitating himself. Other than that, generalizations about his musical palette are risky.

For me, Kuhn is a surfer of the undercurrent, a master of the musical oxymoron. He can summon full-throated roars out of the keyboard, but as he’s doing so, he can still make you suspect that he’s parodying himself. Conversely, his smallest, quietest piano gestures seem imbued with a coded significance. He never approaches the piano with something to prove, but he always gives you something to think about.

Kuhn was born in Brooklyn in 1938, making him 10 years Jordan’s junior. His long career is dotted with other great collaborations—he’s worked with Stan Getz, Steve Swallow, Steve Slagle, Ralph Towner, Gary McFarland, Oliver Nelson, Toshiko Akiyoshi, and most memorably for Kuhn, John Coltrane. His body of recorded work on ECM (a series of brilliant LPs and CDs, intermittently released from 1974 to 2008) represents one of the label’s most consistent accomplishments, in which Kuhn remains himself, ever searching, ever self-effacing, even within the gloss of ECM’s signature reverb. For more detail, see Michael Fitzgerald’s Kuhn discography.

At the Regatta, his solo spot wove four songs together—Leonard Bernstein’s “Lonely Town,” Henry Mancini’s “Two for the Road” (the wryness of this choice became apparent to me only in hindsight), Jerry Brainin’s “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes,” and his own “Oceans in the Sky.” Rhythmic pulses ebbed and flowed, the music went from introspection to whimsy to swing to introspection to declamation with utter confidence and ease. Nothing special, just another marvelous Kuhn adventure.

In 1971 Kuhn began writing songs with lyrics and in some cases, singing them himself. These pieces seemed arch, weird, off-kilter, until Sheila Jordan joined his group in 1979 and showed the genius in them. Consider his greatest hit, “The Zoo” (once known as “Pearlie’s Swine”):

Send twenty dollars to me

So that I can be free

To see

How birds eat their food in the trees

Ham

How I love to eat ham

Vultures don’t give a damn

Meat

Monkeys eat with their feet

So that when I’m alone

Left with only a bone

On top of the sky

Birds are wondering why

At first this unfolds cheerily over a near-bossa beat, the harmonies saying, “This is just a nonsense ditty, after all,” until they darken under “when I’m alone” and the song leaves you wondering about the persona—is it Kuhn (or Pearlie), compassionately gazing upon the zoo’s inmates or is it one of those caged animals, maybe a jungle cat, melancholy and envious of the birds above? And why is it that you feel so sad all of a sudden?

The Kuhn/Jordan partnership has been one of the luckiest things ever to happen to either of them and for us as listeners. Playground, their debut CD together, was a revelation when it first appeared in 1975—not a “singer plus rhythm” session but a collaboration among musicians where the singer is one among equals (Manfred Eicher’s mix emphasized the relationship by keeping Jordan a little farther back than most producers would have). I have listened to it over and over since then, loving the symbiosis of Kuhn, Jordan, bassist Harvie Swartz, and drummer Bob Moses, and gradually coming to believe that its beauty is eternal. (ECM reissued it in 2008 as part of a three-CD Kuhn box entitled Life’s Backward Glances.) Subsequently, the quartet recorded a set of Kuhn compositions based on Robert Creeley’s poems (“Home,” 1979) and a live date that mixed Kuhn originals and standards (“Last Year’s Waltz,” 1982). Kuhn and Jordan renewed the partnership on Jordan-led dates for High Note in 1998 (“Jazz Child”) and 2002 (“Little Song”).

The Regattabar recital was similar in repertoire to the October Jordan/Kuhn duo performance on NPR’s Piano Jazz (the show is available on demand). As in the radio broadcast, they did Oscar Brown’s “Humdrum Blues,” Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation” (with a great lyric written by Jordan’s old, Detroit running buddy Skeeter Spight), Abbey Lincoln’s “Bird Alone,” Sheila’s biographical blues, a Don Cherry line for which Sheila wrote lyrics called “Art Deco,” and “Dat Dere.”

All of these tunes are familiar parts of Jordan’s book, and “Dat Dere” has been part of it since her very first recording date. But, for some reason, probably because my ears were especially open at the Regatta, the Bobby Timmons tune with an Oscar Brown lyric became more than a fun song, and it showed how much Jordan’s life and art blend into a seamless unity. She introduced the song as she often does, reminiscing about the baby talk of her daughter and the way in which they grew up together. The lyric is built around the questions a wide-eyed child might ask of a beleaguered parent (“Who dat in my chair? . . . Where do we get air?”), and I confess that most of the times I’ve heard it I’ve thought of it as a harmless bauble, with a sweetish, my-kid’s-growing-up-so-fast-and-someday-I’ll-be-nostalgic-for-what’s-annoying-me-now kind of theme. But when Jordan sang it at the Regatta, she ever so slightly highlighted two barbed questions near the end that throw the song into a different light: “Mama, what is fair? And why I gotta share?” And when the lyric talked about time marching on, Kuhn slipped into a martial figure that had a slightly sinister aspect. Together, they made this slight vehicle momentarily profound.

The Kuhn/Jordan partnership has been one of the luckiest things ever to happen to either of them and for us as listeners.

When they perform together, Kuhn’s tunes are always part of the program, and, because these compositions are so enigmatic, they make more direct songs like “Good Morning Heartache” and “Falling in Love with Love” better by contrast. They opened with “Gentle Thoughts,” where the line, “What do I know?” allowed Jordan to drift into one of her sung monologues (“I know that I’m glad to be here in Boston, I know that I’m happy to have Steve Kuhn playing the piano . . .”). “The Zoo” was included, of course. Jordan also sang a request, “Tomorrow’s Son,” the lead tune on their first LP together, a song she’s rarely performed since she was in Kuhn’s band. It’s a dark-night-of-the-soul kind of song, but when Jordan sang it, the lyrics shone with her blithe spirit, and it became, improbably, an affirmation of a life lived well:

. . . This moment

Of my lifetime

Has become the hardest thing

I’ve had to face,

As the walls all around my life,

All around the years,

Very special years,

Fall apart . . .

Time to run away . . .

Empty colors

Show the sadness

In my longing for so much,

So many things I’ll never know . . .

Kuhn must have thought himself a very lucky composer at that moment to have such a nuanced reading.

She concluded the set, as she often does, by saying, “I’ll see you next time—and if not, I’ll see you in heaven.” A few hours later, Sheila Jordan celebrated her 83rd birthday.

One final picture from November 17 follows: During “The Zoo,” Jordan slipped away from her scat chorus to sing about how she thinks composers are the best interpreters of their own lyrics and then glided to the piano where she held her mic so that Kuhn could sing. When he finished, he kissed her wrist. Like a line from one of his songs, that moment seemed both evanescent and perfect.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Wow, Steve! And to think we sat at the same table! You hear and see sooo much, in such rich context. Your pal, Fred

Thank you Steve, for capturing the magic of the evening.

The whole evening was special, but I was particularly touched by Sheila’s version of “Tomorrow’s Son,” , which she said she hadn’t performed in ages.

I wonder if Sheila even remembers saying this, it went by so quickly , but as she agreed to do the request, before she started singing, she said ” I’ll try, I’ll try, nothing beats a failure than a try”

And that is really, it isn’t it.. To be at home in creativity and authentic expression all we have is the “try “and the confidence in the attempt. Being in the moment and going for it.

In this case,without question, there was no failure ,only a successful and nuanced performance. But even if she had forgotten the words or felt she had not succeeded in some way, it would have still been a magical authentic truthful moment.

I want to thank Sheila, for that reminder

Thanks for your sensitive, fulsome, and accurate piece.

I would add that her voice is actually improving with age !!

(And it was beautiful when she was young.)