Arts Commentary: The End (?) of Ignoring the Death of Arts Criticism

By Bill Marx

Essentially, Michael Kaiser’s plaint about the vanishing critic is useless because he and so many other cultural kingpins worried about the end of professional criticism offer no solutions.

I just saw this article (below) over at the Huffington Post. It is good that arts honchos are beginning to fret over what myself and others warned about over a decade ago—that the rise of the web means the death of criticism in newspapers and magazines, which have jettisoned serious arts coverage without much thought. Not just the New York Times but the New Yorker as well are cutting back. Pauline Kael would not be able to clear her throat in the column inches the magazine’s movie critics are currently given. And see many dance or jazz reviews in the New Yorker lately?

Unedited and ethically challenged blogs are not the same—and to add insult to injury, journalism schools are beginning to teach that arts reviews in the future will be three minute YouTube videos. Personal, short, and mindless effusions rather than criticism will become the norm. So any one high up in the industrial cultural complex who realizes that the arts demand substantial criticism, which articulates the value of the arts in our lives, is welcome. Still, Kaiser doesn’t help his case when he writes, “But it is difficult to distinguish the professional critic from the amateur as one reads on-line reviews and critiques.” It is not that hard—the professional knows that reviewers need to back up judgments with reasons so that readers can evaluate critics by seeing how they reached their evaluations. Many bloggers spew verdicts—but they won’t or can’t offer the rationale for their decisions.

Essentially, Kaiser’s plaint is useless because he and so many other cultural kingpins worried about the end of professional criticism offer no solutions. No suggestions for support, no ideas about how the cultural community can encourage meaningful criticism of the arts, no talk about funding journalism schools that teach how to write significant criticism.They are scared at what they see, but not to the point of wanting to do something. Perhaps they dream that somehow time will reverse itself and the mainstream media will go back to “the good old days.” Fat chance—there is a generation growing up that does not read criticism. Its view of the arts and of reviews is shaped (some would argue dumbed down) by an over dependence on peer groups and social media.

Does Kaiser think that professional critics are going to pop out of the ground? There are dozens of schools for every art form you can think of, from creative writing to visual arts, etc. But there are only a handful of places dedicated to cultivating and training professional critics.

If Kaiser focused on suggesting ways of improving the mediocre quality of faux-professional arts coverage on the web, such as at the Huffington Post, he would be doing a more valuable service. If he is scared now, just wait until standards of arts criticism have been completely blog-ified.

When will the arts moguls realize that pointing out that the patient is dying isn’t of much use? I suspect at the death rattle of the last professional critic.

The Death of Criticism or Everyone Is a Critic

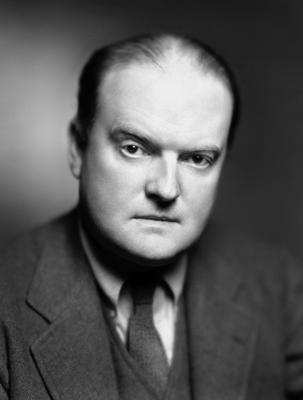

by Michael Kaiser

President, John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

One of the substantial changes in the arts environment that has happened with astonishing speed is that arts criticism has become a participatory activity rather than a spectator sport.

Every artist, producer or arts organization used to wait for a handful of reviews to determine the critical response to a particular project. And while very few critics for a small set of news outlets still wield great power to make or break a project (usually a for-profit theater project which runs longer and therefore needs to sell far more tickets than any other arts project), a larger portion of arts projects have become somewhat immune to the opinions of any one journalist.

This has happened for three reasons.

First, far fewer people are getting their news from print media. There is a reason the newspaper industry is in trouble. Advertisers are spending less in print media because fewer people are reading hard copy newspapers. And for those arts projects aimed at younger audiences, hard copy newspapers are no longer a central element of a marketing strategy. Younger people get virtually all of their information online, through news web sites, social media and chat rooms. And older people are increasingly getting their information online as well.

Second, because serious arts coverage has been deemed an unnecessary expense by many news media outlets looking to pare costs, there are fewer critics and less space devoted to serious arts criticism. Even the New York Times’ arts section is dominated now by features and reviews of popular entertainment — television, movies and pop music — rather than serious opera, dance, music or theater.

And third, the growing influence of blogs, chat rooms and message boards devoted to the arts has given the local professional critic a slew of competitors. In theater circles alone one can visit talkingbroadway.com, broadwayworld.com, theatermania.com, playbill.com and numerous other sites. Many arts institutions even allow their audience members to write their own critiques on the organizational website.

This is a scary trend.

While I have had my differences with one critic or another, I have great respect for the field as a whole. Most serious arts critics know a great deal about the field they cover and can evaluate a given work or production based on many years of serious study and experience. These critics have been vetted by their employers.

Anyone can write a blog or leave a review in a chat room. The fact that someone writes about theater or ballet or music does not mean they have expert judgment.

But it is difficult to distinguish the professional critic from the amateur as one reads on-line reviews and critiques.

No one critic should be deemed the arbiter of good taste in any market and it is wonderful that people now have an opportunity to express their feelings about a work of art. But great art must not be measured by a popularity contest. Otherwise the art that appeals to the lowest common denominator will always be deemed the best.