Dance Review: Bel Tells — Cédric Andrieux through the lens of Jérôme Bel

The second installment in Debra Cash’s coverage of the ICA’s ambitious Dance/Draw series.

Cédric Andrieux Concept by Jerome Bel and with Cedric Andrieux with excepts of works by Trisha Brown, Merce Cunningham, Philippe Trehet and Jerome Bel. At the Institute for Contemporary Art, Boston, November 4–6, 2011.

By Debra Cash

(Debra Cash’s previous piece on Dance/Draw was Lining It Up.)

Over the last decade, we have been inundated—and have become inured—to literary memoir. Self-inquiry-as-performance has spilled onto stages, galleries, and out-of-the-way environments where live art resides. Personal history has become as ubiquitous on stage as the tell-all, celebrity autobiography.

It would be easy to shoehorn Jerome Bel’s 80-minute, theatrical performance-cum-autobiographical sketch of French dancer Cedric Andrieux’s into that genre. Bel, a Parisian stage director who likes to call himself a philosopher, established a template for dancer-centric portraits when in 2004 he staged a frank, approaching-the-audience monologue studded with choreographic excerpts for Veronique Doisneau, a Paris Opera corps de ballet member who was on her way to retirement. The 2005 film of that work, shot in the cavernous beauty of the Palais Garnier is on view in part upstairs in the ICA’s Dance/Draw exhibit.

Other profiles in the series present Brazilian ballerina Isabel Torres, Thai classical dancer Pichet Klunchun, and modern dancer Lutz Förster, who worked with Pina Bausch, Robert Wilson, and the José Limòn Dance Company.

Andrieux and Bel became acquainted at the Lyon Opera Ballet when Andrieux danced in one of his works. That piece, “The Show Must Go On” (2001) is at least in part a Duchampian readymade. In the excerpt, we are told about in Cedric Andrieux, all of the dancers in the company walk up to the stage apron. Then, with the house lights up, they stand and regard the audience. The 1983 Police hit “Every Breath You Take” plays. Sting warbles “I’ll be watching you.” And the dancers watch the audience! That Bel! What a comedian!

(I won’t generalize about the French or anyone who thinks this is a grand, transgressive joke about turning the tables between performer and audience, which I’m sure includes many Americans. I’ll only admit that Andrieux is right when he says this is one piece where the dancers have no chance of getting injured.)

Bel ran into Andrieux on a train from Lyon to Paris, and the two worked together to develop Bel’s “documentary” portrait. Andrieux walks onstage wearing a hoodie, gym pants, and white athletic socks. He proceeds to tell the story of how his mother was intrigued by what she recognized as the oppositional energy of 1968 in contemporary dance and had no problem sending him to dance class, although a teacher memorably set her expectations for him pretty low by suggesting that dance would “be good for his personal development.” At 16, despite what he still believes are inadequate natural gifts, Andrieux was accepted into the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris.

Andrieux recounts this history deadpan; only the soft sibilance of his French accent seems to take us into his confidence. Tall, blonde, and chiseled, he presents his monologue with such self-effacement that it seems that he is willing himself to grow ever paler and disappear. Psychological insights and insider stories have been deliberated expunged; all that is left is maddening neutrality. The big self-exposure is Andrieux’s show and tell to answer any lingering questions the audience might have about what male dancers actually wear under their unitards.

Dancers have been sharing their lives on stage for decades, both in recorded voice-overs and speaking while dancing, so Cedric Andrieux is no Garbo Speaks! moment. I can’t tell you how many college-level dancers—and some who might otherwise be expected to know better—have presented didactic dances with narration about their parents, heartbreak, or struggles in coming to terms with various cultural and sexual identities.

But whether Bel recognizes it or not, the stakes are higher in Cedric Andrieux. In 1999, after a stint with Jennifer Muller that got him to New York, Andrieux joined the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. The master was already 80 and no longer demonstrating his choreographic instructions. Instead, he was following the randomly generated suggestions of a computer program, constructing phrases like realtime tinker toys.

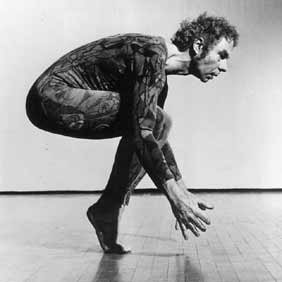

While Bel’s Cedric Andrieux implicitly questions the nature of artistic opportunity and why a dancer takes a certain route in his or her career, it is evident that Andrieux was well-suited to deliver Cunningham’s work. You see that when he’s showing a bit of the solo that won him a prize at Conservatoire, Philippe Trehet’s Nuit Fragile. Trehet’s choreography already harkens towards Cunningham’s style, with the dancer’s central pillar of the torso held like a ship’s mast against lashing arm and leg gestures, the same phrases done in different directions as interchangeable “points in space,” and the work’s overall plain-spokenness.

Later in this portrait, when Andrieux dances excerpts from Cunningham’s Biped and takes Merce’s own role in Suite for Five, he passes through a shape made iconic through a photograph of Merce crouching with his knees forward and his back and arms rounded, a perfectly balanced egg. It remains beautiful.

The memories of Cunningham dancers including Andrieux will be the first draft of history. Merce Cunningham died in 2009 (two years after Andrieux left). This past month, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis held a 10-day festival showcasing its remarkable acquisition of Cunninghamabilia: sets, props, costumes, and documentation that includes works by Cunningham’s important visual arts collaborators. Bel’s work was part of the museum’s extensive programming.

About halfway through his performance, Cedric Andrieux recounts the first time he saw Cunningham’s work live. He was already living in New York. During an outdoor performance, he found himself looking at the stage, looking at the trees, looking at other members of the audience, and then returning his attention to the dance “without fear of having missed anything.”

When the Cunningham Company gives its final performance this coming New Year’s Eve, we will finally have to contend with what we have missed.

C 2011 Debra Cash

Tagged: Cédric Andrieux Concept, Dance/Draw Series, ICA, Jerome Bel, Merce Cunningham, Philippe Trehet

Debra, I am in full agreement -it was a beautiful, compelling, performance for both what was and what was not revealed. The nature of wearing a unitard and dancing the unforgiving impossible transitions of Cunnigham’s work was the window into the strength and vulnerability of the artist.