Visual Arts Review: Flowers as the Work Table for the Imagination

Inescapably erotic, flowers are all about desire. What are they but a glorious exhibition and frame of their own genitals?

Global Flora: Botanical Imagery and Exploration. At the Davis Museum, Wellesley College, through January 15, 2012.

What is it with flowers, anyway?

This beautifully curated exhibition links the history of botanical imagery with early adventurers and with contemporary effects of globalization.

What is it with gardens? When we go to the ends of the earth to find and document species and to gather their seeds, what is going on? Why do we have this urge to propagate—by seed, tuber, bulb, or cutting—or by painting or writing?

The Garden of Eden, Pardes.

It’s no secret that when we construct a garden, it can be a reflection of our private conception of Eden. Our word “paradise” goes back to an ancient, eastern Iranian word for “walled enclosure,” which came to mean, by the first century BC, through Greek translations of the Hebrew “pardes,” a park, garden, or orchard. It’s odd and wonderful to think this way—that something we construct in our back yard goes so very far back that it leaps into metaphor or myth, something primal, perhaps predating scripture.

Is my garden a being? A sort of communal being the way a Portuguese Man of War is made up of many separate individuals? If a book of poems can be thought of as one higher order poem, then is a garden a flowering plant? Whatever she is, I have to go out and talk to her every morning and evening.

Objects of Desire

Inescapably erotic, flowers are all about desire. What are they but a glorious exhibition and frame of their own genitals? If you have ever watched a cat rolling in the catnip, or a bee in an orchid, or a man burying his face in a rose—if you have ever been attracted to someone wearing perfume derived from flowers—you know that the desire of flowers jumps all boundaries between species.

Meanwhile, flowers seduce us by attending to all our senses. Thus they get us to do their bidding. We spend days on hands and knees, weeding to give them more room, watering and feeding, lopping and pruning, hopelessly enamored and enslaved.

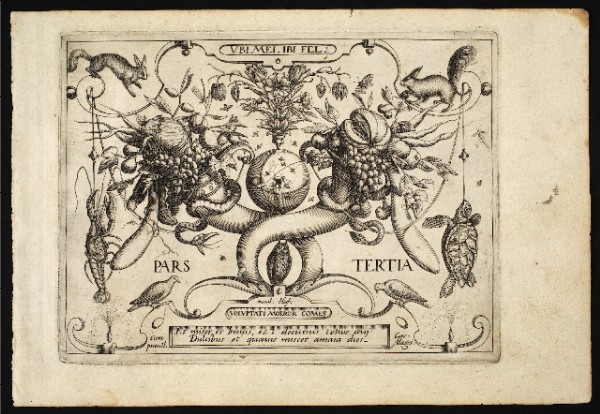

Jacob Hoefnagel, FRONTISPIECE, PARS TERTIA from Archetypa Studiaque Patris Georgii Hoefnagelii(…), 1592. Engraving.

This frontispiece of the third part of a book of engravings by Jacob Hoefnagel after the paintings of his father Joris (Georg) Hoefnagel shows the fecundity of the natural world. Framed by Latin epigrams and surrounded by meticulously observed plants and creatures, honey bees circle around a spherical hive, which is a model of the globe. The bulk of the composition, with its crossed cornucopias burgeoning into different species, is oddly reminiscent of the human female generative organs, fallopian tubes and ovaries.

Beauty Leads to a Strange Hunger

William Jackson Hooker, OPENING FLOWER from Victoria regia; or Illustrations of the Royal Water-Lily, 1851. Hand-colored lithograph by Walter Hood Fitch. Wellesley College Library, Special Collections.

The beauty of flowers can be refreshing and addictive. Refreshing in the sense that it satisfies and at the same time makes us want more. As though we were in love, we want to replicate and broadcast both the beautiful object and our feelings for it.

As Elaine Scarry points out in the chapter “Imagining Flowers” from her marvelous Dreaming by the Book, staring at beauty is a way of prolonging contact with it.

Flowers do command our fierce attention. But in my experience, we can only stand and gaze for so long. We get stiff, we get the chills, or our companions think we are becoming strange. So we draw or paint or photograph or write about the flowers that captivate us. These are more permanent forms of private witness; they are also form of propagating—as Scarry would say—by means of mental pictures. Even arguing about flowers, or simply describing them in a letter to a friend, are ways of increasing our contact.

Sometimes imaginings are not enough. At home we pot up actual cuttings and thrust them on our dubious friends. Collectors and propagators travel to find specimens such as the giant water-lily above, Victoria regia, found in South America and brought back to the Queen’s gardens at Kew. These flowers are 13 inches across, while the leaves grow to five feet in diameter and will support a person weighing around 150 pounds.

Then, too, the strange hunger for the beauty of flowers can shift to a hunger for ownership and thus can lead to poaching. For me, the first time it was dogtooth violets–just a few, from trespassed woods. They all died. This hunger is greater in some of us than others. With patience and practice one gets better at the poaching.

William Jackson Hooker, ANALYSES from Victoria regia; or Illustrations of the Royal Water-Lily, 1851. Hand-colored lithograph by Walter Hood Fitch. Wellesley College Library, Special Collections.

Our fascination with the beauty of flowers can make us want to know what goes on inside, what makes this water-lily tick. And in order to find out, we dismember and dissect, re-enacting the central paradox of biology: what we come to know by such observations is the disturbed organism, the flower cut into gorgeous bits as in Analyses above.

Only when we can convince ourselves that we are looking at the Other can we dissect. What a way to treat the other. What if plants willfully cut us apart, to know us, and thus themselves, better?

We think of plants and trees as largely still, and perhaps our locomotion is part of what lets us feel that we and other animals are superior: we dance and spin about. In the end, though, even we are not so good at avoiding earthquake, tidal wave, or grief.

It turns out that plants and trees are not still at all. David Attenborough’s film The Private Life of Plants shows us plants in constant, shockingly purposeful, motion. Upwards, downwards, outwards. We don’t normally see these moves because their velocity is below the patience-threshold of our gaze.

Edward Joseph Lowe, THE ADIANTUM CONCINNUM, from Ferns: British and exotic, 1862-66. Wellesley College Library, Special Collections.

This Adiantum concinnum or Polished Maidenhair Fern is from volume III of Lowe’s eight volume set about ferns. What sort of hunger would make one write eight books about ferns? Although they don’t have flowers, the delicate and dancing contrapposto combined with a staggered arrangement along the central spine makes this plant seem to feather the light.

Anna Atkins, ASPINDIUM GOLDIANUM, from Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns, ca. 1850. Cyanotype Wellesley College Art Museum.

This cyanotype, or blueprint, of a Goldie’s Fern shows another fascination of ferns: they appear to show a fractal self-similarity. The frond is made up of leaflets made up of smaller sub-leaflets, each having roughly the shape of the whole. Here there are only three levels of self-similarity, but there are ferns with four levels, that is, they have sub-subleaflets. This leads to the question whether these subdivisions might go on for ever, though not visible to the naked eye.

Is it this hint of the mise-en-abime that enchants us here? Are we nudging up against the sublime?

Ferns reproduce asexually. While spores are visible on the underside of leaves, there are no buds, flowers, or seeds to remind one of sex or genitalia. I wonder if aside from the obvious beauty of their feathery symmetries, the absence of sexuality could have had something to do with Pteridomania or Fern-Fever, the Victorian craze for collecting ferns in the wild and then using them in every sort of decorative art. This mania was in its peak from the 1830s to 1890s.

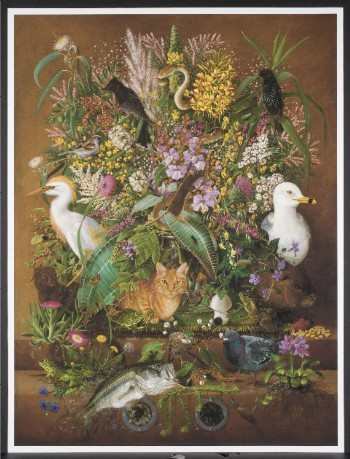

Isabella Kirkland, ASCENDANT, from the series Taxa, 2006. Inkjet print of oil paint and alkyd on canvas over panel. Wellesley College.

Sometimes floral desires inspire a different sort of search for knowledge. Rather than cutting things apart, Isabella Kirkland in her brilliant series of six paintings, Taxa, looks at how plants and their animal contemporaries are affected by humans and how they are currently faring in the United States in terms of introduction, invasion, decline, and extinction. The product of huge amounts of ecological research, Kirkland’s superbly accurate works echo the technical mastery of Dutch, 17th-century botanical images. Her canvases are beautiful and overwhelming; each shows so many species that it is best to go to her website for the species key. Visitors are invited to view actual plant specimens depicted in these works at the Wellesley College Botanic Gardens.

Ascendant, Kirkland says, “shows nonnative species that have been introduced in some part of the United States or its trust territories. They are all on the increase as they successfully out-compete native residents.“ If you enlarge this one and look at the expressions of gull, cat, or egret, there’s a subtle, sly look of satisfied pride.

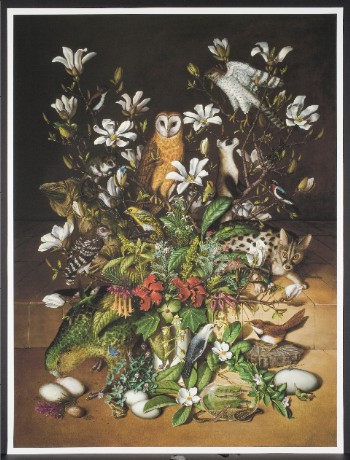

Isabella Kirkland, BACK, from the series Taxa, 2006. Inkjet print of oil paint and alkyd on canvas over panel. Wellesley College

Kirkland says about this one, “The plants and animals in this picture have gone to the brink of extinction and been carefully husbanded back, or were presumed extinct and then re-found.” There are around 48 species in this one. Here on the faces of the genet, the owl, and the owlet, there seems to be a look of tentative, surprised pleasure.

Flowers as the Work Table for the Imagination

Flowers take hold of our senses and our emotions; they make us fall in love with them; they impel us to scientific research at all levels from microscopic to environmental. But they also involve themselves with the intellect, in particular the imagination. Elaine Scarry, in the book mentioned above, claims that flowers are very easy for us to imagine with great vivacity. It is much more difficult, she says, for us to form a mental picture of a landscape, or a large animal, or the face of a close friend. She gives four reasons for the ease with which we can form mental pictures of flowers:

1) They are usually smaller than our heads (consider the nasturtiums here rather than the giant water-lilies above).

2) Their shape is related to the curve of our eyes and retinas.

3) Flowers have an “intense localization of color with a sudden dropping off at the edges.”

4) Their leaves are gauzy or translucent, their petals thin; gravity seems not to act on them very much.

But this is not all! Scarry goes on to make an astonishing argument: once we imagine blossoms, she says, we can use our mental image of their petals as the surface or work table on which we imagine other, more difficult things.

Dr. Robert John Thornton, THE NIGHT-BLOWING CEREUS, from Temple of Flora, 1800. Mezzotint, printed in color, with watercolor additions. Wellesley College Library, Special Collections.

In a wonderfully murky scene from Dr. Robert John Thornton’s masterpiece, Temple of Flora, the church clock stands at two or three minutes past midnight; the flower has opened to its full radiance; the full moon is partly obscured, but its reflections gleam on the rippled water below.

On the print itself, a small caption reads, “Flower by Reinagle. Moonlight by Pether.” In fact, Pether was a landscape painter who was so fond of nocturnal scenes that his nickname was “Moonlight Pether.” (A collection of his moonscapes can be found online, here.)

There are several varieties of night blooming cactus that go by the name Night Blooming Cereus; this one is Selenicereus grandiflorus, or Moon Cactus, which for some reason Thornton calls Night-Blowing. The flower blooms for a single night, then wilts grotesquely. Captivatingly fragrant, the open flower is huge, bigger than your face.

Why are we so amazed by size, so awed when our Turk’s cap lilies grow to be nine feet tall or those water-lily pads in the botanical gardens are five feet across? Why do we take size so personally? Don’t we feel it in the gut?

Is it that we remain, in our minds, the measure of all things? Is it that “small” is smaller than our palm, and “large” is bigger than our heads, and “soft” is softer than our flesh?

In any case, a flower as large as the cereus has to be taken seriously. Even leaving aside its maddeningly attractive scent. You have to talk to it as an equal, never using the language we use with babies or small dogs.

Dr. Robert John Thornton, THE DRAGON ARUM, from Temple of Flora, 1812. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

I can’t resist bringing in to this discussion two of Dr. Thornton’s other illustrations from Temple of Flora. They are not visible in the Davis Museum’s Global Flora, simply because the vast book is in a case under glass and we cannot turn the pages.

Thornton was a public lecturer on medical biology, and he knew the darkness of flowers as well as the light: many of the plates in his Temple of Flora are as melancholy and brooding as the Night-Blowing Cereus, and you wouldn’t want to venture into his dismal landscapes alone.

Occasionally he goes wild in his descriptions as well, as when he takes on the Arum Dracunculus or Dragon Arum:

This extremely foetid, poisonous plant will not admit of sober description; let us therefore personify it. SHE comes peeping from her purple crest with mischief fraught: from her green covert projects a horrid spear of darkest jet, which she brandishes alof; issuing from her nostrils flies a noisome vapor infecting the ambient air; her hundred arms are interspersed with white, as in the garments of the inquisition; and on her swollen trunk are observed the speckles of a mighty dragon; her sex is strangely intermingled with the opposite! Confusion dire!—all framed for horror or kind to warn the traveler that her fruits are poison-berries, grateful to the sight but fatal to the taste, such is the plan of PROVIDENCE and such HER wide resolves.

This is one of the things I love about Thornton: how thoroughly he reminds us that the gaze with which we look at Nature is always refracted by the lens of Self. Plants do not grow out of context, even if we isolate them to look at them more coolly and scientifically. It is always a specific one of us, personal and peculiar, who acts as observer. Thornton, by his choice of the painters he commissions and throughout his own descriptions, reminds us, in a way that the other artists and writers in this exhibition do not, that every observer has a psyche and that the watcher is in constant feedback with the flower under observation. The flower and the mood of the viewer affect each other unavoidably. While it is said that he places his flowers in their native contexts, it is sometimes the geography of the psyche that often interests him the most.

In contemporary, botanical writing, I think Jamaica Kincaid’s Among Flowers: A Walk in the Himalaya most brilliantly brings out this interplay between the nature of the plant and the nature of the viewer.

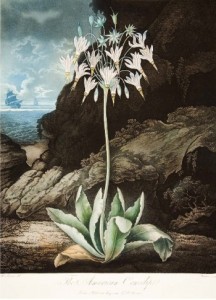

Dr. Robert John Thornton, THE AMERICAN COWSLIP, from Temple of Flora, 1801. Collection of the author.

Some flowers Thornton clearly loves: his view of the the American Cowslip or Shooting Star is mild and gracious. He calls it “a vegetable sky-rocket in different periods of explosion,” and “a number of light shuttlecocks, fluttering in the air,” and notes Linnaeus called it Dodecatheon after the 12 Olympian Gods on account of its singular beauty and the multiplicity of its flowers.

Each blossom here is at a different stage of development, from the immature bud through full flower to final seed pod. Against the glowering background, the plant seems to radiate light as it demonstrates the cycle of life, decay, and rebirth from seed, echoing that luminous and mortal progression that resides in the inner consciousness of the gardener. I talk about this image more in my book Hinges: Meditations on the Portals of the Imagination.

What Is It about Flowers, Anyway?

Although flowers are not geographically vast nor spatially infinite, aesthetically no matter how we try to capture them, in the end, what we come to see is that we can not understand the immensity of their beauty or the vastness of their effect on us. And in grasping that inability and the consequent awe it inspires in us, perhaps we are discovering not the feeling inspired by the hurricane, or the rare and foreign waterfall, or the infinity of number, but one that we can put our face up against, that we can hold in our palms, the intimate sublime.

Tagged: Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Galleries, art, flowers

Wonderful piece and images. Thank you!

Another excellent review. I have to say, I’m as taken by botanical images as I am by the real things! Consider me seduced into heading over to Wellesley to see these gorgeous images. Is there a catalogue of the show?

Thanks so much. If you do head over there, the whole Davis Museum is a gem! As for a catalogue of Global Flora I am not sure. I didn’t see one.

This is wonderful. Flowers art philosophy emotion procreation creation. Have you heard of flower essences? People make healing potions with the essence of a flower. It is truly and endless fascination.